Luke Healy's Permanent Press is a book so meta (and so self-deprecatory) that I almost expected it to disappear after I read it. Ostensibly, it's a volume that collects two longish stories from Healy, "The Unofficial Cuckoo's Nest Study Companion" and "The Big And Small". The former story was previously published in minicomics form, and an extremely clever, original achievement. The latter story was previously unpublished, and in this book it's often interrupted by the metanarrative of Healy and his shadow. That shadow is part conscience, part Greek chorus, and part therapeutic wise mind to the Healy character's constant and depressive self-deprecation.

That self-deprecation is more than just the sort of funny-sad window dressing that's at the heart of so many autobiographical comics. Indeed, Healy is brutally sending up that entire sub-genre of comics at his own expense, as is made clear by the hilariously melodramatic quality of these interludes. For example, after a horrible experience at a local comics show, his shadow suggests that he go outside and get some "fresh air." That turns into a two-month sojourn in the wilderness (complete with poop jokes) that frees Healy from thinking about comics... until he does so again immediately upon coming home.

Healy satirizes his crippling self-doubt and need for external validation in the form of awards for his comics. The only thing that can get him back to the drawing board is a conversation with his father. Not because he's getting encouragement, but because his father is constantly telling him to quit comics and join his accounting firm. Later, he turns into a cartoon rat as he starts to ignore his own self-care, and his therapist turns out to be his shadow. When the rat says, "I'm terrible at saying things... but I'm good at making comics, I think," Healy hits on something important.

As always, it is instructive to turn to the work of Lynda Barry. In her book on writing, What It Is, she enumerates the Two Questions as the enemy of every artist. Prior to that, she notes that drawing in particular is a kind of play, and play is essential to the mental health of every child. She also notes that play is deadly serious for every child, and while it is a form of agency, it tends to be intuitive. In neurological terms, play bypasses executive functioning, the part of the brain that helps us organize tasks and execute them in a deliberate manner. At a certain point in our development, and then throughout our lives, the aforementioned two questions arise: "Is this good? Does this suck?" When one deliberately sets out to make something "good," with the same sort of mental state as completing a task, we take away the very conditions necessary for creation as well as its psychological benefits.

Externalizing the worth of one's work leads to a labyrinth of second-guessing from which it's impossible to escape. It makes the artist forget that drawing and writing is a pleasurable activity. In Healy's book, he gets back to work when he's reminded not just that he feels like he's not good at anything else (the text), but also that he doesn't get the same kind of enjoyment in doing anything else (the subtext). That enjoyment is not just the sheer act of creating, but also of being able to plunge one's own personal issues into the crucible of the drawing table and emerge with intricate, nuanced and beautiful examinations of relationships, the urge to create and the barriers we set up for ourselves.

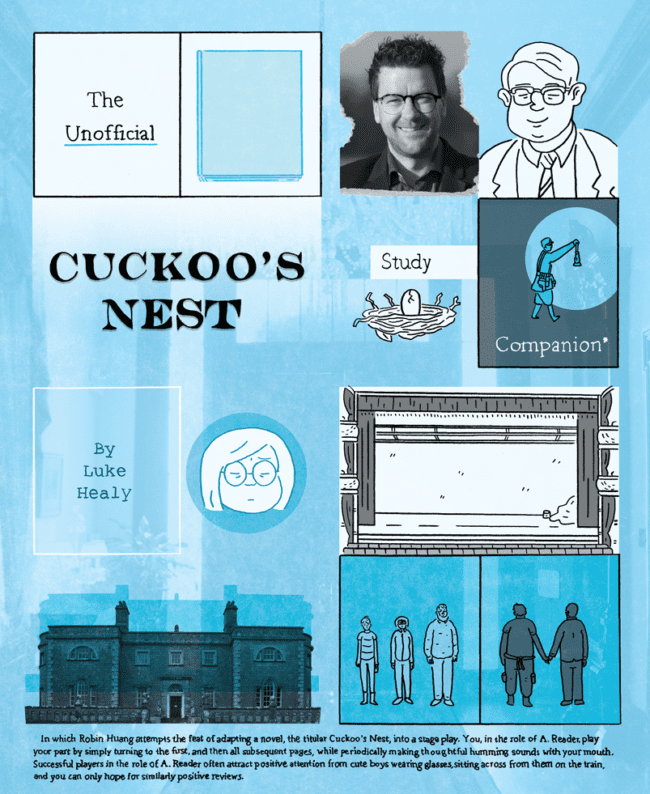

Take "The Unofficial Cuckoo's Nest Study Companion", for example. It's a comic in the form of a three-act play's script, where individual panels in a constant four-panel grid turn into their own four-panel grids, long blocks of dialogue going back and forth between characters, and other formally clever devices. It's a comic that's a play about a director who's trying to adapt an obscure literary novel into a play for the stage. The director, an Asian woman named Robin, is trying to recover the glory she had lost after a disastrous adaptation of Macbeth which featured more lines for Lady Macbeth. That it is an Asian woman (a double outsider) directing a woman to talk more that receives such a negative reaction is not a coincidence. The book is made by a nervous author who resembles her ex-husband (a photo is plastered atop his face whenever she looks at him) who somehow won a major literary award.

The book is about a son trying to find his father, who abandoned him years ago. He manages to find his house and spends the bulk of the story simply walking around it, looking around. There is no real ending. As such, it is nearly impossible to put on stage, although the set designer has an elaborate, pulley-based system that would shift and create new rooms on stage. He moves too slowly in building this stage and any "help" he gets with his maniacally personal vision result in accidents. This was my favorite metaphor of the story, as trying to reduce something that is in actuality irreducibly complex will only lead to breakdowns, physical and otherwise. While the drama in the story points us to Robin, the author Dave, and the set designer Wally, Healy uses some nifty misdirection in getting the reader to ignore the central relationship in the book: that of Robin and her teenage daughter Natalie.

Natalie is in constant trouble with her school because of her conflicts with her literature teacher, whom she thinks is an idiot. Robin is set obsessed with this job that she ignores her until Nat is suspended, and Robin hires her as an intern for the play. The reality is that Nat is the one character who has real insight into everything and everybody around her, only nobody will listen. The essence of her observations is this: wasting time trying to fix an event from the past is completely pointless. It is a lesson that every character has to discover for themselves in the story. There are any number of other lessons to be learned, like it's important to listen to others and set aside preconceived notions, that the world is a far smaller place than we might think, and that the encomiums of an audience of strangers is far less important than genuine connections with our loved ones. Above all else, it is impossible and irresponsible to try to connect to an absent figure in one's life when there are actual people needing attention.

There are swerves and surprises in the story that humanize all of the characters in unexpected ways. Nat is not only a character who demands to be heard from her mother, she also works as a metaphor as Healy's own shadow/conscience, just as Robin is Healy's stand-in. The story works perfectly well on its own, but the background material that Healy writes deepens the reader's understanding of "Cuckoo's Nest"; the stuff with Healy and his shadow is a companion to the companion. We learn that Healy has issues with his father. We learn that he's afraid of not being recognized and thus not existing. Nat skewers another Healy stand-in in Dave, who tries to write himself out of his bad relationship with his father but is told that all the words in the world can't actually change the past.

"The Big And Small" is another story that speaks to the way Healy's formal decisions are just as important as his clear-line drawings in creating the visual language for the book. Every page has two tiers that are roughly devoted to one of two characters: Amir or Mo. Mo lives below Amir, and the only interaction they have at the beginning of the book is Mo's anger at Amir practicing his trumpet in the morning. The central metaphor of the story is the essential meaningless of size distinctions in a universe where we are so tiny and insignificant.

One thing about Healy's comics is that they are explicitly about different expressions of queerness. A relationship between two men in the first story turns out to be a crucial part of its plot, and the slowly revolving and evolving relationship between Amir and Mo is the centerpiece of the second story. One can see the reflections of the cartoonist in each character: the trumpet playing Amir considers his mukbang YouTube videos (wherein he records himself eating) his true form of expression. For Healy, comics is his only true form of expression, as other forms of communication sound "wrong" to his ear. Mo flies into anger instead of being able to communicate his needs and complaints. Like "Cuckoo's Nest", the story is ultimately about the artificial barriers that we put up that prevent us from hearing and truly connecting with others and how to break them down.

The stories focus on those connections, but Healy as the artist is always and ever alone, except when his shadow is there to talk to (and eventually ignore). While he makes light of that metaphor and his "struggles" in particular, it's clear that finding ways to connect is at the core of his work. The barriers that we and others create to prevent those connections tend to repeat as the central conflicts in his stories, even in one based on a true story like How to Survive in the North. Whatever real-life connections Healy might have aren't relevant to this book, because the struggle here is about the artist's ability to communicate this need to himself and others. The recognition he craves is parodied, but what the book makes clear is that what he really wants as an artist is to be seen, recognized and understood. Even though his means to get there is complex and sophisticated, the urge is still that of a child at play, intuitively creating narrative as a way to understand themselves and others, often as a prelude to reach out and create, sustain and treasure relationships. This is the rare meta work of art that finds a way out of its own maze and encourages the reader to do so as well.