To say that Joe Sacco is the greatest practitioner of comics journalism working today is an understatement; “comics journalism” is a concept that existed before him, but it was he who gave it a name and a reputation and a set of standards that he largely created. Paying the Land may well represent the greatest work he has ever done, and much of its greatness comes from the fact that it accomplishes what only the best journalism can do: it manages to be both timely and timeless at the same moment, telling a story that is acute in its immediacy while also portraying conflicts, struggles, and situations that—as is made clear as it reaches its powerful ending—have the familiarity of the eternal.

Paying the Land begins with the story of how resource-extractive industries—specifically, timber-cutting, diamond mining, and the new, untested, and potentially dangerous method of retrieving oil and natural gas known as “fracking”—have impacted life in the indigenous communities of First Nations people in the Northwest Territories. As with almost any responsible documentary work being done around such crucial environmental issues, the contradictions of capitalism are highlighted from the very outset; we learn about the Dene, the blanket name for the indigenous people of northern Canada, largely through the process of broken treaties, betrayals, theft, and deception employed to strip them of control of the lands they occupied for thousands of years.

But it very quickly becomes an even wider and more complicated story, and it is the strength of both this uncommon tragedy and Sacco’s skills as an observer and reporter that make it transcendent in both its sense of loss and its testament to human dignity and determination. Sacco does not shirk from placing clear blame where it needs to be placed, but he also clarifies that while there are easy villains and obvious wrongs, there are no simple remedies and no obvious way out. Many people in these communities actually champion the use of fracking because it is the only option left to them; they know that the government, and the vast private wealth it represents, will take what it wants, and the best they can hope for is to keep a share of the money for themselves rather than be left with nothing. Sacco also deliberately avoids the trope of the noble savage, of the purity and incorruptibility of the indigenous people; in his masterful interviews with longtime residents and tribal leaders, he lets us share in the early triumphs of their unification and collective will when they all, as Dene, stand up and demand a voice in how their land is used, but he also portrays the tragedy of that unity falling apart and splitting into tribalism when delays and frustration set in and some groups decide to look out for their own above all.

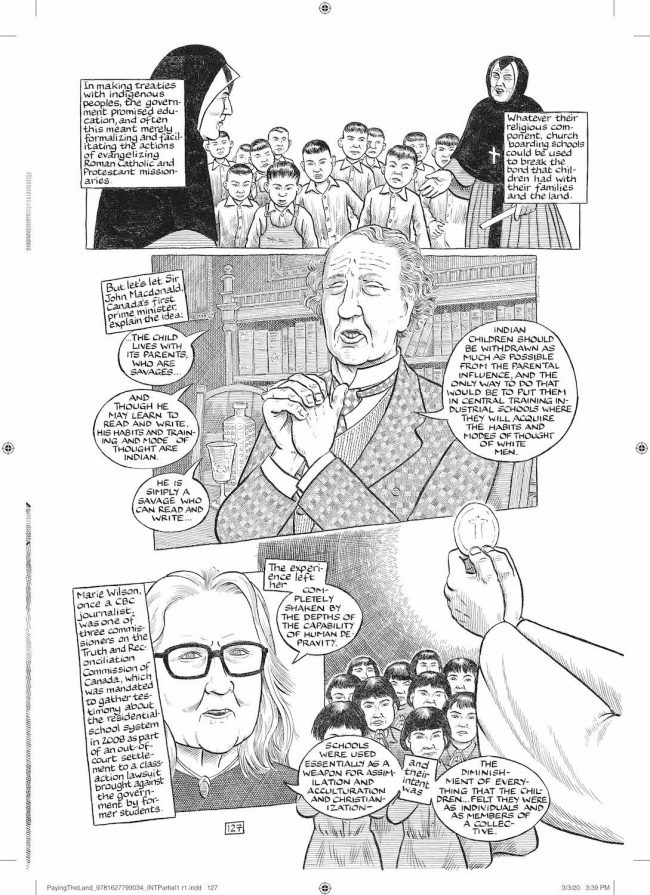

Much of Sacco’s previous work finds him locating a precarious balance between so-called ‘objective’ journalism and recognizing his own role in telling a story, and that does not change here, though he does so less than he has in other books. Perhaps the most startling appearance of his authorial presence is when he stops dancing around the practice of sending indigenous children to “residential schools”—essentially Catholic boarding schools where children as young as toddlers were forcibly taken from their parents through bribes, threats, blackmail, and violence, and educated in such a way as to destroy their cultural identities. It is through this staggering crime that we truly come to realize, long before the oil companies arrived, how stacked the deck was against the native people of Canada, and how factors as intrinsically human as language, personal identity, and concepts of identity were used as weapons against them.

Much of Sacco’s previous work finds him locating a precarious balance between so-called ‘objective’ journalism and recognizing his own role in telling a story, and that does not change here, though he does so less than he has in other books. Perhaps the most startling appearance of his authorial presence is when he stops dancing around the practice of sending indigenous children to “residential schools”—essentially Catholic boarding schools where children as young as toddlers were forcibly taken from their parents through bribes, threats, blackmail, and violence, and educated in such a way as to destroy their cultural identities. It is through this staggering crime that we truly come to realize, long before the oil companies arrived, how stacked the deck was against the native people of Canada, and how factors as intrinsically human as language, personal identity, and concepts of identity were used as weapons against them.

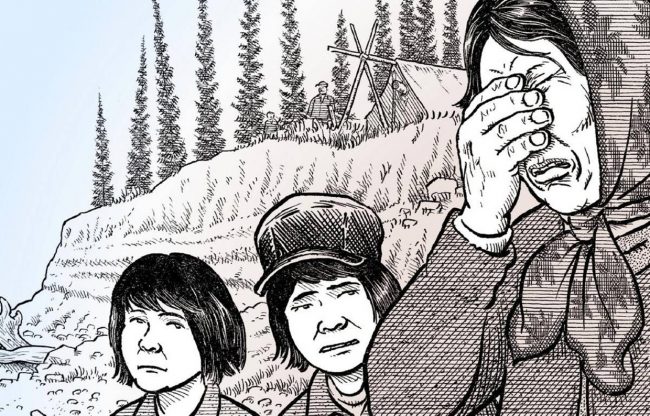

The destruction of the way of life of so many people in such a traumatic way took place over a historical period that, for the Dene—who lived and worked the land for countless centuries—was the blink of an eye. And yet it transformed them in ways so profound and irreversible, it will likely never leave them. Crippling alcoholism (in one town, the coroner informs Sacco that 97% of the bodies he sees died from something related to alcohol abuse), drug addiction, physical and sexual abuse, and a terrifyingly high suicide rate are the legacies of this treatment. And yet, even among the elders—many of whom still recall growing up in the bush and hunting to live—there is no consensus as to how to address these legacies. Take the oil companies for their ready money, or throw them out? Return to the old ways, which were often hard and cruel, or embrace modernism, whose technology and ease is costly and discourages group cohesion? emand compensation from the government, or reject it as fostering dependence? The Dene are left with little but to find solutions to problems they had no hand in creating.

This is one of the most ambitious works in comics journalism; Sacco has been in worse conditions and written of more dangerous situations, but here, he is attempting to capture not just a snapshot of a moment in history, or a story bound by dates and circumstances, but an entire way of life that is, one way or another, disappearing. He spends time in small towns, draws lined faces and gnarled hands, and depicts the vastness and persistence of a majestic nature that is slowly disappearing and being converted into numbers in some far-away bank accounts. It is certainly the finest art he has ever rendered, and the way it builds and shapes itself from chapter to chapter is like the best documentary work in that it begins with one thing and ends with something entirely other, while never taking a turn that doesn’t feel natural or earned.

This is one of the most ambitious works in comics journalism; Sacco has been in worse conditions and written of more dangerous situations, but here, he is attempting to capture not just a snapshot of a moment in history, or a story bound by dates and circumstances, but an entire way of life that is, one way or another, disappearing. He spends time in small towns, draws lined faces and gnarled hands, and depicts the vastness and persistence of a majestic nature that is slowly disappearing and being converted into numbers in some far-away bank accounts. It is certainly the finest art he has ever rendered, and the way it builds and shapes itself from chapter to chapter is like the best documentary work in that it begins with one thing and ends with something entirely other, while never taking a turn that doesn’t feel natural or earned.

By the time the book concludes, it’s easy to forget that it was ever about fracking at all, but at the same moment, the shadow of the land looms over everything, now in the hands of men and women who don’t respect it enough to pay. It’s a work of journalism that leaves you with a thousand questions and a sense of injustice as large as the sky, but it does so while never leaving the words and actions of individual people, living out the consequences of that injustice on the most human and relatable scale possible. Paying the Land is a masterpiece of reporting; it is a brilliant success in putting names and faces on those our system of living has tried to dehumanize, and in remembering what so many would like us to forget.

By the time the book concludes, it’s easy to forget that it was ever about fracking at all, but at the same moment, the shadow of the land looms over everything, now in the hands of men and women who don’t respect it enough to pay. It’s a work of journalism that leaves you with a thousand questions and a sense of injustice as large as the sky, but it does so while never leaving the words and actions of individual people, living out the consequences of that injustice on the most human and relatable scale possible. Paying the Land is a masterpiece of reporting; it is a brilliant success in putting names and faces on those our system of living has tried to dehumanize, and in remembering what so many would like us to forget.