Fragile male egos have long been the catalyst for conflict in popular fiction. Take, for example, this passage from the story of Aucassin and Nicolette, transcribed by an anonymous author in the twelfth century, in which Aucassin is addressing his captive lover: “Be sure that if thou were found in any man’s bed, save it be mine, I should not need a dagger to pierce my heart and slay me. Certes, no: wait would I not for a knife; but on the first wall or the nearest stone would I cast myself, and beat out my brains altogether.”

The male ego gone awry has been a theme in Dan Clowes’ work since the beginning of his long and spectacular career. One thing that makes his best work so indispensable is his rigorous examination of the topic from many perspectives, both male and female. Even very troubled characters become sympathetic thanks to his uncanny ear for dialogue and his trenchant sense of humor.

In Clowes’s fifth graphic novel, Ice Haven, the young Charles, whose intellect far outstrips his years, meditates at length on sex, consciousness, and morality. He yearns to free himself, and all humanity, from the clutches of the procreative urge. He wonders during a lengthy monologue: “Does all violence rise from distorted sexual impulses?” The punch line of the strip, revealed to the reader in the final panel, is that the young boy is in love with his stepsister. In Clowes’s graphic novel from 2011, The Death-Ray, two adolescent friends, Andy and Louie, struggle to understand the true nature of Andy’s superhuman powers. At one point Louie councils Andy, “Sure you’ve got some powers, but that’s nothing without motivation. Look at the Hulk—his wife died or something.”

And it’s the murder of the titular character in Clowes’ latest graphic novel, Patience, that motivates her distraught husband of six years, Jack Barlow, to acquire the means to time travel.

From the time of her death in 2012 until time-travel technology is developed in 2029, Jack lives a Spartan existence, focused only on finding his pregnant wife’s killer. A chance encounter with an alien prostitute leads Jack to the inventor of the time travel apparatus. America’s future seems to involve benign aliens who arrive and cohabitate peacefully with humans, perhaps even saving humanity from the perilous effects of global warming, although this is never explored in depth. (One hallmark of Clowes’ work is his masterful ability to imply impending societal collapse while remaining focused on his protagonist’s immediate personal dilemmas. Consider the germ warfare in David Boring or the roving gangs of feminist terrorists in Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron).

Jack travels back in time to Patience’s early adulthood, and is shocked to witness two acts of abuse committed against her by two different men. He knows that preventing her murder is his primary objective — allowing him to reunite with his wife in the present. But along the way he struggles with the morality (and consequences) of delivering vigilante justice to Patience’s attackers.

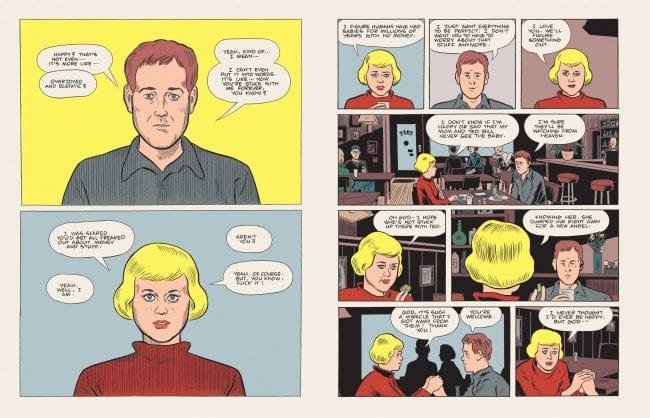

Before I go any further into the story, however, it is critical that I stop and discuss the absolutely transcendent artwork. When my partner Lane and I opened the PDF that was sent to me for review, we both let out an audible “OOOoooohh,” as though we were watching fireworks. Clowes’ saturated, candy-bright hues evoke the mind-altering world of pre-Code EC fantasy and horror comics, drawn by artists including Jack Davis and Bernie Krigstein, and colored by women like Marie Severin. When Jack finds Patience’s body, he is rendered almost as though insane from grief, his figure distorted against a background of solid color, like a Steve Ditko figure. The time travel sequences, which depict distorted abstract shapes writhing across panels to represent movement across a cosmic void also evoke Ditko. Jerry Grandenetti’s phenomenally psychedelic work for DC’s Silver Age Spectre title comes to mind as well. Some moments when Jack is suffering from the transformative effects of his travels also invoke Bernie Wrightson’s work on Swamp Thing and even the physical distortions of Jack Cole’s Plastic Man. I would argue that Patience is Clowes’s most beautiful book to date.

Given the high quality of the artwork, and Clowes’s mastery of his subject matter in his earlier works, I was surprised to find that the book as a whole didn’t measure up to my expectations.

Patience is the titular character, and yet I had trouble accepting her as a fully realized individual greater than the sum of her traumas. We see vignettes from her difficult early-adulthood, but we know almost nothing of her life from the moment she meets Jack in 2006 until she’s murdered in 2012. Clowes’s treatment of the couple’s financial concerns and class issues in general is very compelling, but we infer that she’s not working, and she’s never shown engaged in any hobbies or activities (apart from a few therapy sessions). We learn that before she met Jack, she was doing very well in college, but was forced to drop out due to financial concerns, but we don’t know what she was studying or what career she hoped to pursue.

Meanwhile, as the story progresses Jack Barlow more and more resembles Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s hardboiled, hyper-masculine private detective. Midway through his quest to save his wife and unborn child he wonders, “What the hell am I doing exactly? Do I really want to save that baby, or am I just some bloodthirsty ape out to reclaim his manhood?” By this point in the story, I firmly believe the latter to be true. In contrast, here’s Jack contemplating the trauma Patience suffered in her early twenties: “Here’s this innocent little girl who only wants somebody to love her and she just keeps getting shit on by monster after monster until she doesn’t know which way is up.” Jack also says of Patience: “That girl’s an angel, she’s got a heart of pure gold.” This calls to mind a scene in which Marshall and Natalie, the main characters in Clowes’ 2011 Mister Wonderful, are eating dinner together on their first date. Marshall looks at Natalie and thinks to himself, “Look at that, eating her cake like a little girl, so innocent and guileless.”

Harry Naybors, the fictional comics critic in Ice Haven, poses the question, “Is criticism ever really about its ostensible subject, or is it primarily an expression of self definition?” I absolutely believe that criticism reflects the personal tastes of the critic rather than the value of the artwork in question, and over the course of my life I’ve tried hard to define myself in opposition to the classic Madonna/whore dichotomy that has been present in fiction since the dawn of written language. Ghost World is such a magnificent exploration of female sexuality and friendships between women that it’s hard to accept clichéd depictions of women from its author.

Clowes is certainly aware of these clichés, and I believe that his intent is to call them into question, to parody them and to examine the types of wish fulfillment they represent in our culture. But pop culture mutates so rapidly that sometimes it outstrips its commentators.

I am a lifelong sci-fi buff, and my first impulse as an adolescent was to watch classic films from the 1950s and '60s. I vividly remember how excited I was to watch The Fly, from 1958, starring Vincent Price, and how disappointed I was with the movie itself. The pace of the film was molasses slow, the dialogue was wooden and the special effects seemed painfully quaint. That’s why I was so thrilled when I discovered David Cronenberg’s 1986 remake, which featured outrageous special effects and scenarios that added up to a complex meditation on masculinity, scientific discovery and the frailty of the human body. Then in the 1990s, TV shows like Mystery Science Theater 3000 and Buffy the Vampire Slayer took vicious enjoyment from piercing the veil and exposing the one-dimensional nature of classic science fiction tropes. The success of those shows is part of the reason that even mainstream superhero comics and movies have become increasingly more self aware and more tongue-in-cheek. That impulse to “wink” at the reader seems present at times in Patience. At least twice Jack stops to make some very “meta” jokes about his predicament. On page 63 he states, “All that sci-fi bullshit is just too much to wrap my stupid-ass brain around,” and here he is again on page 118: “I’m so sick of this science fiction mind-fuck bullshit.” But then the conundrum for me is that Clowes seems to be attempting to combine these parodic elements with meta commentary and elements of literary fiction in order to give his story more gravitas and formal structure. But because I have difficulty accepting Patience and Jack as fully developed characters the story is unable to transcend the genre tropes in which it’s rooted, and winds up not one thing or another.

Like such contemporary writers as Karen Russell, Junot Díaz and Jonathan Lethem, Clowes has time and again demonstrated his ability to explode genres, creating uncanny, eerie and wonderfully detailed portraits of mutants, madmen, sociopaths, tyrants, teenagers, fetishists, best friends, and aspiring creative types. When reading Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, for instance, I felt profoundly unsettled because, although the book features elements of popular fiction such as mutants, cults and rogue cops, the story is completely unpredictable and takes on the quality of a nightmare rather than a horror movie. Patience never quite takes flight like that.

And yet it’s impossible not to feel awe when considering Patience. The awe one feels when considering a work of tremendous ambition made in good faith by an artist at the peak of his skill. It is much safer and easier never to attempt a mighty feat of storytelling. The attempt opens the author up to the possibility of failure and renders him or her vulnerable. Clowes has never been afraid to put human motivations under a microscope or to investigate the things that make us alive. This bravery is one of the most important qualities an artist can possess.