This is the premier minicomics anthology series, told with an emphasis on relative accessibility in terms of narrative. It's a comic that in general mixes collaborations with single-artist works and has been a staging ground for longer works (like MK Reed and Jonathan Hill's Americus). The design, production, and attention to detail on this series have always been eye-catching and carefully considered, and the latest issue is no exception. This issue is a bit of a departure in that every story is written by well-known zinester and occasional cartoonist Jason Martin, best know for Laterborn. He's paired up with a who's-who of small press cartoonists who illustrate each story, and the result is a beautiful, frequently moving comic that's one of the best minis of 2011.

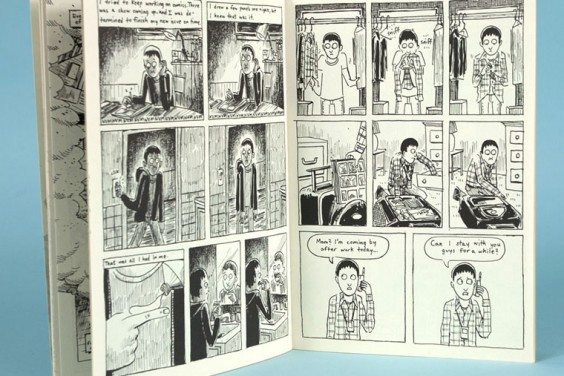

Martin alternates minor, quotidian observations & memories (a la Harvey Pekar) with longer, more significant memories. "The Weeper", drawn by Jesse Reklaw, is one of the more emotionally powerful stories in the book. What starts as Martin recalling his childhood pastime of drawing his own Batman comics turns into a meditation on his inability to control his emotions as a child, and how in some ways he's disconnected from them as an adult. Reklaw alternates between a highly polished version of his naturalistic style and the cruder line of a child when we see pages from Martin's story about the Weeper, a Batman villain he created. He's the opposite of the Joker; his mouth is frozen into a frown with tears burned into his face. Martin reveals that this character was obviously a manifestation of his sensitivity as a child, crying frequently and often for seemingly silly reasons. It's a matter-of-fact story that nonetheless reveals much about its author.

In terms of tone, Martin's stories switch between wistful and regretful. "Nickelodeon" (drawn by Corinne Mucha) is about how not being able to watch certain channels on TV as a child is a representation of all the things he never got to experience (and never will). On the other hand, "Streetlight" (drawn by Francois Vigneault) is about a particular teenage memory, of seeing a woman driving by and eagerly wondering what she was singing. "The Weaving Of A Dream" (with distinctive art by Vanessa Davis) describes meeting the author of a children's book when he was in elementary school and how her devotion and passion to her art was a clear inspiration to him. "Meditations" is all about listening to the titular album by John Coltrane and the incredible power to be found in its intent and effect; Hellen Jo is a perfect choice of artist given her dynamic style. "Avo" is a bittersweet story about Martin's grandfather drawn by Sarah Oleksyk; the clearness of her line and sharpness of facial expressions was crucial to getting across the moment of recognition that comes across his face when he calls his grandson by name after not having recognized him due to a stroke.

The other major story in this book, "Scenes from the Fire", is an episodic series of mental snapshots about a fire at his apartment. In a sense, it's less about the actual events of the fire than it is about the way we deal with trauma and how the sense of smell is a powerful catalyst for triggering memories. The story's artist, Calvin Wong, captures the sheer shock, terror, and weirdness surrounding the fire, as well as the less-then-comforting policemen and sleazy insurance salesmen. In the most poignant chapter finds Martin seeing a firetruck two years later and flinching at the smell of fire. As detailed later in the story, one of the effects of the apartment fire came when fumes from burnt plastic suffused everyone's nasal passages and made his home (which was otherwise mostly unharmed) completely unlivable. The final page of the story is a soothing one both for the reader and Martin, after the harrowing events depicted earlier.

Like Pekar, Martin manages to create a smooth synthesis with a number of different artists working in several different styles. The cartoonier lines of Jo and Mucha are more in line with Martin's own art, so it is interesting to see his stories illustrated by Reklaw and Oleksyk. Each of these artists is careful to bring something very specific from their style to Martin's story. In Reklaw's case, it's the tension between crude childhood drawings and a more "mature" style. In Oleksyk's, the subtlety of her line and facial expressions wind up being the most crucial elements of the story. I don't know how closely Martin worked with the artists or if it was Means who made certain suggestions on what to emphasize and which artists should draw what story, but the bottom line is that it works. This is an experiment I'd love to see repeated, perhaps on a larger scale.