Scott McCloud died for somebody’s sins, but not mine - leastwise, thanks to Understanding Comics I know full well that single-panel “gag” cartoons aren’t actually comics. I mean, except for that they are, which should illustrate the hazards of using formalist weights and measures to dictate a question usually defined by history and context.

All of which is to say, three new books by Norwegian illustrator Øyvind Lauvdahl have recently crossed my transom - Ontography: a catalogue (of being!) is the first, followed by Ontography: a catalogue (of being!) Also and Ontography: a catalogue (of being!) Too. These books are handsome and well-designed - they sit in the hand well. The design philosophy is stark and simple: no dust jacket or color, just a cardboard cover. The publishers, Utenfor Allfarvei Forlag, have done an excellent job presenting Lauvdahl’s sketchbooks, which in this case are a series of single-panel studies, usually featuring some manner of pithy legend. Single-panel “gag” cartoons, albeit very depressing ones.

“Ontography,” in case you were curious, is an interesting word with a lengthy pedigree. Given that ontology is the branch of philosophy dealing with questions of being, ontography would in turn be related somehow to printing or writing on the same subject. (“Geology” is the study of the earth, “geography” the study of human measurement of that same earth, for comparison.) Looking around online, the most accessible definition of the phrase I found was a chapter from a 2012 Ian Bogost book called Alien Phenomenology, and the second chapter therein: “Ontography: Revealing the Rich Variety of Being”: “Let’s adopt ontography,” says Bogost, the emphasis in the original, “as a name for a general inscriptive strategy, one that uncovers the repleteness of units and their interobjectivity.”

If that seems about as clear as mud: one of the goal of Bogost’s field of study is to work on the philosophical relationship of the universe to mankind. It’s a challenge to discuss nature outside out its relation to humanity, a challenge to language, framing, and consciousness itself to consider the value of nature in-and-of-itself. So, a phrase like “Ontography” exists to reference, to return to Bogost, “an aesthetic set theory, in which a particular configuration is celebrated merely on the basis of its existence.” I mean, sure.

If that seems about as clear as mud: one of the goal of Bogost’s field of study is to work on the philosophical relationship of the universe to mankind. It’s a challenge to discuss nature outside out its relation to humanity, a challenge to language, framing, and consciousness itself to consider the value of nature in-and-of-itself. So, a phrase like “Ontography” exists to reference, to return to Bogost, “an aesthetic set theory, in which a particular configuration is celebrated merely on the basis of its existence.” I mean, sure.

Why am I discussing any of this? Because, as I think I said earlier, three new books crossed my transom. And although these three books are all sketchbooks, they all arrive with the same doorbuster of a title. And I was left to wonder, as I was flipping through these pages, just how seriously we were supposed to take that title? Because, having left grad school a while ago and - furthermore - having studied a bit of the Object Oriented Ontology (or “OOO”) on discussion in writers like Bogost, Meillassoux, and Latour, I felt very strongly that meaning could be wrested from said title in relation to the work on display. But I also didn’t think that said meaning would be very flattering to Lauvdahl himself.

Think about the fact, now, that I haven’t even mentioned the work itself. These are sketchbooks - under most circumstances the very definition of loosely related bric-a-brac put into some kind of loose assortment. The whole idea of an “aesthetic set theory” does make sense when actually flipping through a small book advertised as a catalogue of being. But what precisely is on display here? Each book has precisely 150 sketches, for a total of 450. Each sketch appears to be just a few inches across, printed at least a little bit larger than drawn. The tool in question was a Pilot VBall (we know because there’s a photo of one herein). His caricature reminds me a tiny bit of Eric Powell, actually.

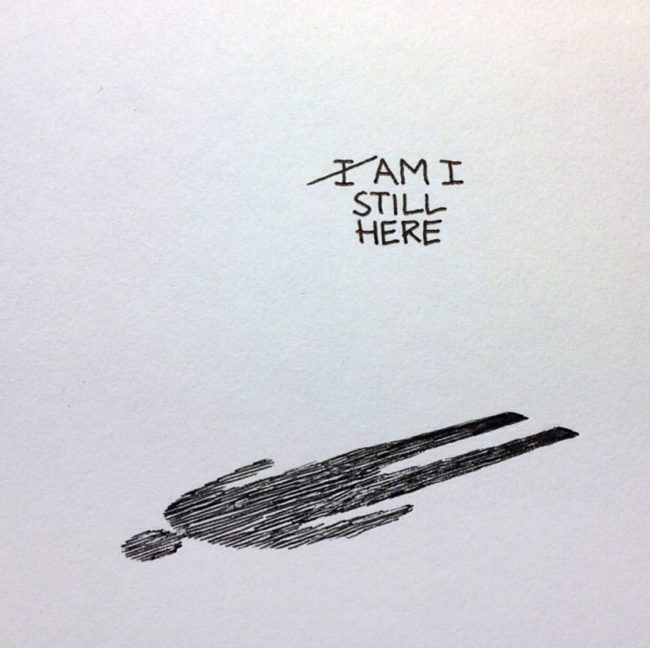

And of what are these 450 tiny ballpoint sketches a catalogue? Well, that’s the thing: they’re all little cartoons about being depressed. The main character is a guy in jeans, a jumper, and sneakers, and he says things like “let’s just try to pretend” after he’s been turned into a cardboard standup, or “nothing is what it seems to me” with a giant hole in his chest. Or, “dreaming you’re not a thing,” while curled up in a ball. There’s little in the way of consecutive storytelling here, but any Scott McClouds in the audience should be happy to know its not completely bereft: the “dreaming you’re not a thing” panel is followed by a drawing of a cardboard box in the same position that reads, “this self assuming flesh.” It scans.

Under normal circumstances my personal policy as a critic holds that sketchbooks are the most interesting and useful tool for understanding an artist. They’re the best way to see what an artist actually knows, what they think, and how they work. A well curated sketchbook can showcase old artists in new light. These aren’t those kinds of curated sketchbooks: these have been clearly intended to make some kind of artistic statement on their own, but the statement is not particularly novel. The title does a good job of counterfeiting that ol’ scholastic rag, but the connection to contemporary philosophy is tenuous and strained, and easily overpowers what is really a slight corpus.

The overall effect of reading these three sketchbooks in one sitting is not so much absorbing the artist’s deep philosophical waxing but seeing precisely where the artist has overstepped, conceptually and in terms of format. There’s a part of me that wants to be kind in the matter, to dismiss the philosophical scrum as precisely the kind of “small-r” romantic gesture to which artists fall particular prey. But there’s a sketch early in the second volume (Also!) with Lauvdahl’s generic Depressed Man turning invisible while the caption reads “specters of marks.” Which is not just a Derrida pun, but a pun about my favorite volume of Derrida, the one that’s about finding hope in the darkest times. There’s no hope here, none of the impish Derridean wit that made even his most laborious manuscripts also fun and exciting artifacts to decipher. Why even mention it?

So it’s puns and in-jokes to contemporary philosophy, erected as a scaffolding around the work of a modern-day B. Kliban. And if that seems harsh, just imagine any of Laudahl’s sketches photocopied and taped onto the work refrigerator: how about the one with the dude sitting there while two fingers poke out from each of his eyesockets and he says “No escape!” It doesn’t have the same ring as “love to eat them mousies!” but you can see the same sort of energy. I’m a bonafide clinical depressive and the overwhelming melancholy and anomie in these volumes doesn’t just border absurdly self-defeating, it spills out onto the concourse. Leave the philosophers out of it next time and try some cats instead.