We may never stop relitigating the 2016 election. (For evidence of this theory, please consult the internet.) There may be no cultural cachet in revisiting the presidential contests of the past, even ones as sexy as 2000, but the curious alchemy that arose from the clash of Clinton and Trump – and good ol’ Bernie Sanders – seems to have sent America into some kind of perpetual loop. Politics are aways personal, but this particular triangulation seems to have hit us deep in our souls; more so than most partisan showdowns, the 2016 election spilled over into our private lives, and we not only feuded with one another on social media, we lost friends, we forsook family, we let love decay as we watched the country lose its mind.

Or did the ascendance of Donald Trump merely expose what was already there? Did the election split open new wounds in our psyches, or did it just expose the damage that was already there? That’s the question that shades every panel of James Sturm’s moving, disturbing, magnificent new graphic novel, Off Season. Politics doesn’t intrude in the narrative in any obvious or arbitrary way; it simply crowds into the lives of its characters in the same ways, big and little, that it does to us all. Off Season isn’t a book with a political axe to grind, in which ideology stands in for our personal problems; it’s a book that illustrates how politics is inextricable from our emotional lives, and functions as both an influence on and a reflection of our interior lives.

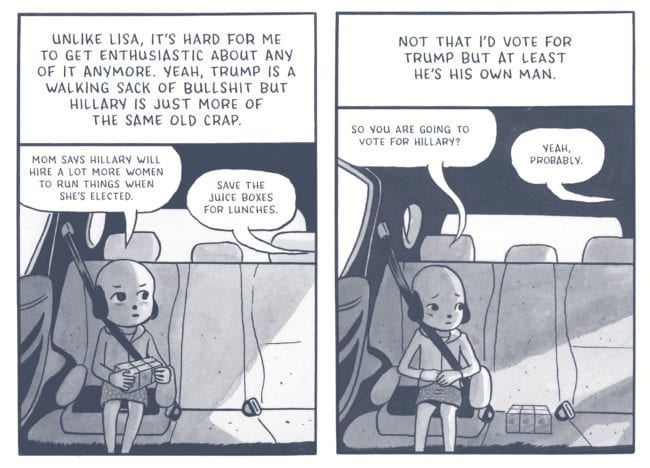

Taking place over a four-month period, beginning just before the 2016 election and ending right after Christmas, Off Season is drawn with all of James Sturm’s potent strengths. Its simple layout belies the great sophistication of the panel composition, and his use of shadings within the gray palate is absolutely stunning. While there isn’t the dynamic range of action that characterizes his 2001 masterpiece, The Golem Mighty Swing, he can still infuse the simplest movements (from children fighting in the back seat to a car skidding in the snow to a cat vomiting) with an incredible sense of motion. Drawing on his work in children’s stories as well as his ability to keep readers always a little off their footing, Sturm chooses to portray all the characters as humanoid dogs; this can be amusing (as when the characters dress like other animals), perplexing (as when actual animals are portrayed in the story), and on occasion, disturbing (as when newly elected president Donald Trump appears on television, his already flabby and distended features transformed into a canine leer). The overall effect is both familiar and strange; there are elements of Disney and Charles Schultz, but it also strongly recalls James Thurber: the simplicity remains, but the crudeness is replaced by craft.

Off Season’s main character is Mark, a contractor recently estranged from his wife Lisa. Their children split time between both of them as they reluctantly circle around the terms of their divorce; the story is seen entirely through his eyes as he struggles to do right by his kids and the woman he clearly still cares about despite blinding flashes of anger and helplessness. Mark’s situation is familiar to many people in the Trump era: he depends on small jobs and steady paychecks, but as with most people without stable employment, he frequently finds himself stiffed out of money he’s owed, dependent on greedy middlemen, or staving off bills until a check finally arrives. He is often resentful of his children (who are demanding and thoughtless in the innocent way that children often are) and has an achingly relatable sense of free-floating hostility: he is in a rotten situation only partly of his own making, and he wishes he could hold someone responsible, but he is powerless to do so.

Off Season’s main character is Mark, a contractor recently estranged from his wife Lisa. Their children split time between both of them as they reluctantly circle around the terms of their divorce; the story is seen entirely through his eyes as he struggles to do right by his kids and the woman he clearly still cares about despite blinding flashes of anger and helplessness. Mark’s situation is familiar to many people in the Trump era: he depends on small jobs and steady paychecks, but as with most people without stable employment, he frequently finds himself stiffed out of money he’s owed, dependent on greedy middlemen, or staving off bills until a check finally arrives. He is often resentful of his children (who are demanding and thoughtless in the innocent way that children often are) and has an achingly relatable sense of free-floating hostility: he is in a rotten situation only partly of his own making, and he wishes he could hold someone responsible, but he is powerless to do so.

We see all the other characters in the story through Mark’s eyes, with all the uncertainty that implies. It’s never made completely clear what ultimately causes his rift with Lisa, but she clearly has mental health issues; he tries to accommodate her but the self-denial this requires leads inevitably to bitterness and hostility. At times, he reviles her and lashes out; at other times (as, when Hillary Clinton’s loss in the election sends her into a spiral of depression, he tactfully hides his father’s MAGA cap, a gift from his conservative brother), he shows surprising tenderness. He’s not entirely reliable as a storyteller, sometimes downplaying his own bad behavior, but at other times being tremendously sympathetic. He is simply trying to navigate a situation he was never able to anticipate, for better or for worse, and Off Season’s entire thematic direction is that our lives never stop being tested and there is no certain way we can react that will prepare us for the next thing to go wrong.

Sturm has a reputation of ending his stories on, to put it mildly, an off note. At this point, it’s more of a stylistic tic than anything else, and he repeats it here: the final scenes of this masterfully designed series of emotionally charged vignettes shows us that vomiting cat – repeatedly – and leaves us with a strange development that isn’t entirely out of the blue, having been foreshadowed at least partially in flashbacks, but like some of his other works, seems like it strayed onto the page from a completely unrelated story. But given Off Season’s focus on the way our public sphere and private lives are unstoppably intermingled, it’s not as jarring as it might be otherwise, and in fact probably winds up the book about as well as anything else. Wherever Mark’s life is headed, he will be negotiating terra incognita both financially and emotionally, and Sturm illustrates this with his pitch-perfect blend of the ordinary and the bizarre.

Sturm has a reputation of ending his stories on, to put it mildly, an off note. At this point, it’s more of a stylistic tic than anything else, and he repeats it here: the final scenes of this masterfully designed series of emotionally charged vignettes shows us that vomiting cat – repeatedly – and leaves us with a strange development that isn’t entirely out of the blue, having been foreshadowed at least partially in flashbacks, but like some of his other works, seems like it strayed onto the page from a completely unrelated story. But given Off Season’s focus on the way our public sphere and private lives are unstoppably intermingled, it’s not as jarring as it might be otherwise, and in fact probably winds up the book about as well as anything else. Wherever Mark’s life is headed, he will be negotiating terra incognita both financially and emotionally, and Sturm illustrates this with his pitch-perfect blend of the ordinary and the bizarre.

In one of the book’s most affecting sequences, Mark hears Lisa crying in the next room. He doesn’t rise to comfort her, out of a combination of exhaustion and stubbornness, but he sees himself doing it anyway, as one does in dreams. His ghost-self awakens, walks down the hall, and climbs into bed with her to provide comfort. But his true self remains motionless. It’s a devastating moment in a book full of such quiet power, and a reflection of how the simplest gestures of humanity can be blocked by circumstances we can neither control or comprehend.