A tangled tale. We’re looking at an autobiographical memoir and a coffee table art book. The art is awesome, the memoir is engaging.

The tale has to do with Malcolm McNeill’s years-long attempts to complete a graphic novel with William Burroughs, a work to be called Ah Pook is Here. Ah Pook, by the way, is a Mayan god of death.

McNeill met Burroughs in London in 1970, when Burroughs was 56 and McNeill 23. They worked on a comic strip together, The Unspeakable Mr. Hart, which ran through four episodes in McNeill’s underground newspaper, Cyclops. The paper folded, but Burroughs and McNeill stayed in touch, hoping to flesh out their comic and create a booklength graphic novel.

What with Burroughs’s literary cachet, and with McNeill’s profound gifts as an artist, they managed to get a contract with Straight Arrow Books, a branch of Rolling Stone magazine. But they didn’t finish the book while the window of opportunity was open. The advance was too small to allow for enough working time. The collaborators were distracted. Burroughs’s text lacks a clear plot or story arc. The plans for the project kept changing. And then Straight Arrow folded.

In the end, no other publishers were willing to print the Ah Pook graphic novel. One complication was that Burroughs and McNeill had moved away from a pure comic strip format—they wanted to mix in blocks of solid text as well as large free-standing illos. And possibly the heat of McNeill’s sexually intense images was an issue. If Burroughs prose descriptions of his visions were but marginally acceptable, it may have been that images of the visions were too much.

What sorts of images am I talking about? One illo from McNeill’s art volume, The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here, shows a city scene like Times Square with hard-core porno images within the billboard ads for, like, Coca-Cola, VW, and Cinzano. The polychrome image sprawls onto a second page that resolves into a slash-mouthed Mayan Charlie-Watts-look-alike lounging at his ease, sporting a huge boner. Another illustration features a bevy of androgynous girls bearing Henry-Darger-style penises, standing in foamy rubble before a torn American flag, arms akimbo, cocks at full salute.

Some of the smaller images take the form of amazing Mayan glyphs—one of my favorites shows a space-suited astronaut recoiling from a high priest…who’s shooting the astronaut with a pistol. A mind-boggling scenario. In one of the conversations that McNeill reports in Observed While Falling, Burroughs mocks the notion of a U.S. astronaut hitting a golf ball on the Moon. Not if the Mayan priests had been there!

Eventually, since the graphic novel wasn’t happening, Burroughs published his text for Ah Pook in a prose collection that’s long since out of print. I happen to own a copy of this antho—I’ve been an avid Burroughs fan for fifty years. I reread the prose Ah Pook while working on my review of McNeill’s books—even though, cockroach-like, the little Burroughs book kept trying to get away from me, scuttling under couches and stacks of paper. Ah Pook is in a characteristic style of Burroughs’s middle period. He mixes a true-adventure story with bitter anti-establishment scenarios, gay sexual fantasies, science-fictional visualizations of chimerical mutants, and apocalyptic visions of a biological plague. An eclectic scumbling of genre prose, anarchist rage, Beat surrealism and homosex erotica.

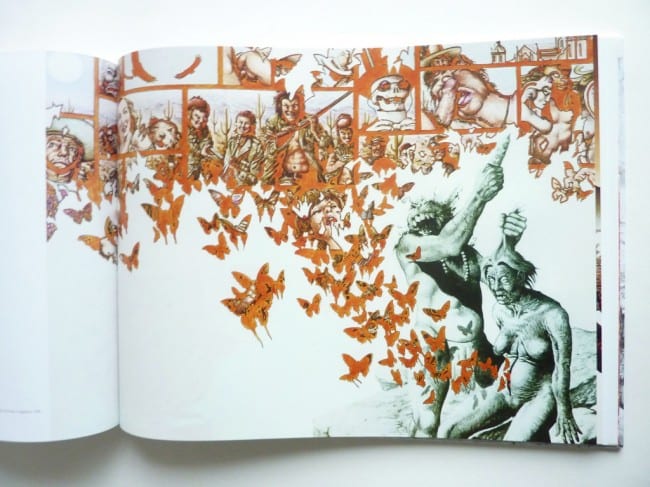

And now McNeill has independently published his complete collection of draft and finished art for the Ah Pook project in his The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here. It’s a gorgeous book, with a unique mix of photorealism, cartoon line and abstract expressionism—featuring the wild kinds of images that I described above. In other illustrations, he creates mad Hieronymus Bosch dog-piles of humanity, or dissolves a comic strip grid into a swarm of butterflies. A weirdly prescient image shows hollow-eyed Arab youths charging towards us through a park. These aren’t silly-ass cartoons, they’re fine art. McNeill has in fact shown his works in galleries, and large prints are available online.

His memoir, Observed While Falling, gives us the tale of the quixotic project’s various stages, and of some accompanying synchronicities that entered McNeill’s life. Whether or not you care about actual and hypothetical variorum editions of Ah Pook itself, the memoir is fascinating, particularly in its depictions of old Bill.

Burroughs in person was more congenial and civilized than he was on the page. I’d already had some sense of Burroughs as a man from having briefly met him in the early 1980s, and from having read various volumes of his letters—paramount among these collections is his quintessential work, The Yage Letters. I in fact include several chapters of made-up Burroughs letters in my new beatnik SF novel Turing & Burroughs. And here McNeill treats us to a rich buffet of fresh personal anecdotes.

Although McNeill wasn’t gay, Burroughs repeatedly pestered him for sex, urging him to forget girls and come to bed with the old man. McNeill calmly withstood the entreaties, and the banter became something of a game. In any case, Bill wanted a lot of erect penises in the illos for Ah Pook, and McNeill dutifully went to porn movies—often with Bill along—and made preliminary sketches.

The results are staggering—the best pictures of dicks that I’ve ever seen. I think in particular of an image in The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here, showing a Mayan musician with an epic hard-on that reaches up to the strings of his electric guitar. A little insect-man with a curled proboscis and a dangling ball-sack stands on the neck of the guitar. Wonderfully jagged fields of force trail from the guitar to the musician’s hand. This design was made for a 1978 Burroughs-inspired “Cumhu T-shirt.” Cumhu is a Mayan character in Ah Pook. If and where this T-shirt was ever marketed isn’t explained. In any case, McNeill and Fantagraphics should consider reissuing reissue this transgressive T.

One of the pleasures of McNeill’s memoir, Observed While Falling, is reading about hear about his conversations with Burroughs. Old Bill laid down some tasty aphorisms. Here’s a few:

“Of course [heart transplants] don’t work. If the body didn’t want the first heart why the fuck would it want a second one?”

“The purpose of writing is to make it happen.”

“When you talk to yourself, who are you actually talking to?”

If we could fold McNeill’s The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here together with the existing Burroughs text, we’d have a riveting graphic novel. My feeling is that, as Burroughs’s raw Ah Pook text stands, it’s a little too repetitious to fully hold a reader’s interest. McNeill’s illos would add a leavening agent, a yang for Burroughs’s yin, a lightning jolt that would bring the nodding Frankenstein of the text to life.

But, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, the Burroughs estate seems not to want this alchemical union to be consummated. Indeed, McNeill has apparently been required to blank out the Burroughs-prose-containing speech balloons that appear in his reproductions of the 1970 comic that started it all, The Unspeakable Mr. Hart.

Never mind. The impasse is part of the ongoing reality matrix mix. We’ve got the words, we’ve got the pictures, we’ve got the back-story—and it’s fun to collage them in your head.

By the way, as an added fillip, you can find a short YouTube movie by Philip Hunt, featuring Burroughs’s oracular voice reading political Ah Pook riffs over a stop-action video starring a chicken with a rubber head, and backed with music by John Cale. Although well executed, the video is bleak and ponderous. It lacks Malcolm McNeill’s wild and cooking madness, Burroughs’s parrot-bright Mayan science-fiction scenes, and the obsessively iterated boy-on-boy sex scenes.

So what does Ah Pook mean? Let’s give old Bill the last word, as quoted in McNeill’s Observed While Falling. “Nobody seems to ask the question what words actually are and what exactly their relationship is to the human nervous system.”

Ah Pook is a word/image virus. Study these new books and enjoy the disease.