“What do you want to be?” I asked, shaking my reward out of its envelope. It was an intemperate question. In Update #13 to the Mould Map 3 Kickstarter campaign, prospective contributor Blaise Larmee acknowledged a statement he had made on Tumblr to the effect that he'd felt more embarrassed associating himself with Kickstarter than posting images of his penis on the internet. “There's this affective labor that's involved that seems to undermine any ambivalence on the part of the creator,” he remarked. I felt even worse. There is often an anthropomorphizing tendency to the rhetoric surrounding anthologies – something that moves critics to articulate their perspective less on a congress of artists than on an enormous animated wicker man, dozens of shiny eyes flitting open and closed between its ribs as it shambles out across the ashlands that separate us awed and lonely readers.

And some, I admit, almost beg such readings. Do you recall when Kramers Ergot 4 brought hell to Frogtown? Truly a book that glared in your face and dared you to smile back - a large and luxurious production that warranted every expenditure, insofar as the best fucking printing and the most awesome fucking paper seemed necessary for adequate reproduction of every scratch/mark/dab of ink, pencil, and paint; mandatory, yes, to foreground the act of drawing, and the act of beholding drawings, superimposed atop the demands of even refined and literary narration: an art of pictures. And it's not like there hadn't been a soul who'd previously considered a vision of comics that placed the value of pictures in parity, at least, with the value of narrative – anybody could arrive at that conclusion and evaluate accordingly. It's just that the book, Kramers 4, by its production, accommodated its artists so well that they could be seen anew from there.

Mould Map 3, in its opening pitch, promised “Comics for THIS present.” I was a backer; at least one of my editors was too. It was a very tight campaign, only reaching its funding goal within the final two days. As a result, a considerable portion of hype's burden was shouldered by early adopters, wowed by the lineup of top talents promised for the final project - the “reward,” in Kickstarter parlance. It is never quite a pre-ordered book you get from the public-television pledge drive/reality-show voting process/unlockable video-game achievement that fuels your desire to F5, F5, and witness the pledged amounts rise up, up, up toward the goal: it's more like a goddamned spoil of war, and, as in war, a Kickstarter campaign inspires a certain honing of motives into a galvanizing yawp. Artists may desire only the conveyance of beauty, or the exploration of space, but the books their work inhabits may be taken as indicative of the health and well-being of an entire species of art – and those artists spied out of line might be judged according to that frantic narrative.

The function of retrospect, then, could be to burn the wicker man: to extricate artists, ambivalence and all, from this detention, this anthology, itself now gummed up in a hero's journey that culminated with an assurance that art would simply happen. And yet, as sure as two images put together tickle the urge to imagine a sequence, the proximity of comics stories inside one book invite the divination of A Statement, even in the absence of a specific declaration of such from the folks in charge.

Mould Map 3, at least, left its options open. Philosophically.

“An exploration of the ways in which network technologies mediate our experience of each other and our surroundings,” said the Kickstarter. So: a book about the manufacture of discernment. The editors, Hugh Frost & Leon Sadler, even posted their contributor directives online: a barrage of cultural and aesthetic assertions, suggestive of the lone observer trembling from stasis, cocooned between uncaring nature and commodified over-concern. The panic is that something has to emerge from this caterpillar.

What do you want to be?

**

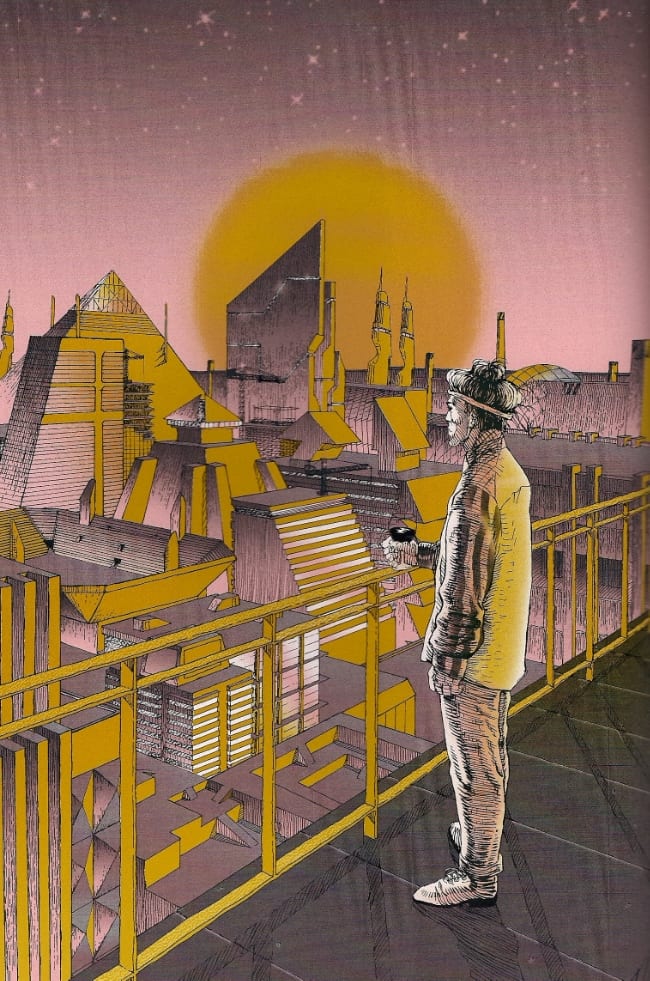

I talked about this book on a podcast, recently. My friend Matt Seneca was particularly taken by an unfamiliar artist: Joseph P. Kelly, who evidently has not yet published an enormous body of comics work. I was impressed by the confidence of his meaty human figures; Matt compared the lead character to the Metabaron - the strapping badass from several of Alejandro Jodorowsky's collaborations with Moebius and Juan Giménez. “Finally,” I thought, “we have artists who not only look like they've read Métal Hurlant, but could have been published there too.”

And Kelly's narrative, I must say, carries some of the bleak, oppositional force of those late '70s pieces. There is no dialogue. The Hero lounges in a chair with a glass of wine in his hand, in front of a portrait of a man with an automatic weapon and a belt of grenades. The Hero's closet is filled with boxes, books, and guns, but what he removes is a photograph of himself and a woman, both posing with weapons. Sitting by a pool, the man then envisions her naked and bobbing. His home is enormous; everything in the world is toasted orange, as if perpetually heated by fire. From a balcony, he views an immense futuristic city, juxtaposed with the facing page's flashback to the Hero and his woman firing shots from a speeding car on a dirty urban street. The two are lovers, soon lying nude atop a sparse bed in a ratty hovel. And then:

That's the end of the story. What to make of that final twinkle in the eye? It's very supercilious, I think – Kelly has done some work in contrasting present/future-tense luxury with annihilation amongst the past/present-tense poor. The girl is immolated, but hey: that's war. Don't you just love a manly narrative? A lone survivor? A last man rich from winning and standing apart? A proper Hero?

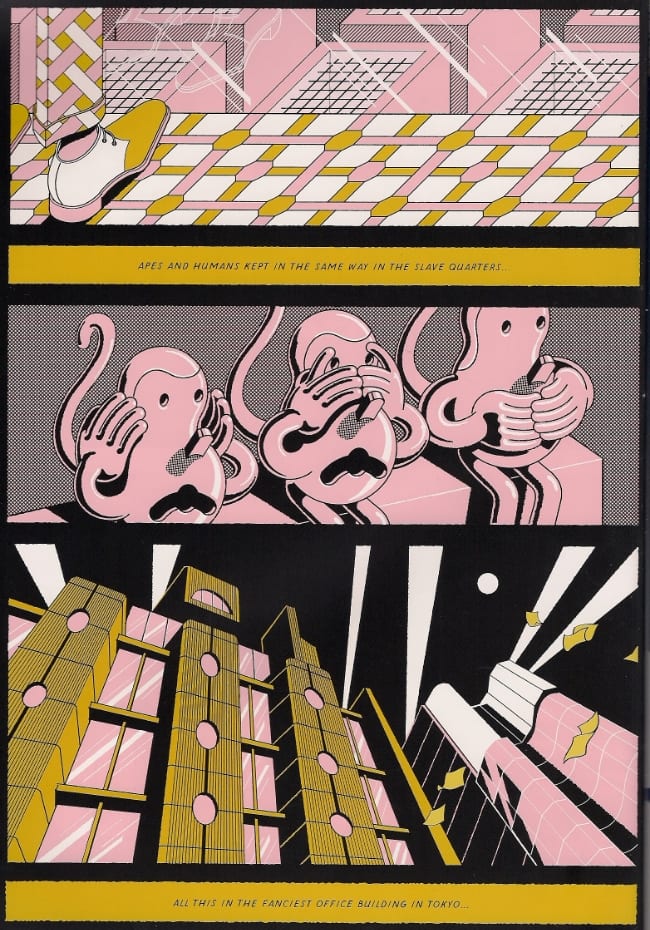

“Lando,” in contrast, is a slightly better-known artist, having worked for years in the Decadence collective he co-founded; recently, he contributed some art to the Image SF series Prophet, propelling him temporarily into hundreds of North American comic-book stores. He assesses his own depictions of soldiers at war as “a way of confronting the lack of consciousness and the industrial nihilism that exists within society as a whole.”

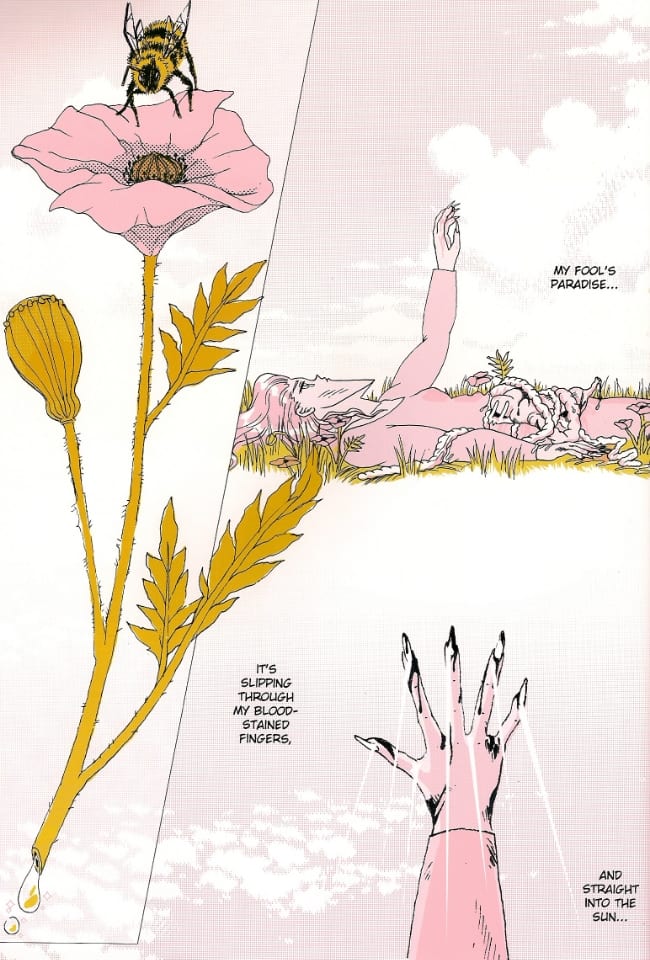

At 13 pages, his piece is the longest in Mould Map 3. Again, there is no dialogue. Again, the story concerns a man and a woman: escapees, we might surmise, from a city patrolled by air with drone-like contraptions that drop eggs of viscous fluid on citizens dressed for flight. Parts of the city walls are overgrown with vegetation, though; climbing above and around this urban labyrinth, the pair soon find themselves in a room full of odd spores – if Kelly's future is forever burning, the pink and tan of Lando's world implies flesh and dirt. Suddenly, a wheat-like stalk sprouts from the man. The woman raises a gadget in defense, but the man points his finger at the speed of the growth; she cannot save him. The two lock eyes for four panels. She puts the weapon away, and embraces him, and the growth seizes her body, and:

We needn't view Lando and Kelly in competition, or even dialogue, but their stories share a critical point. Kelly's Hero comes to rule his empire of metal pyramids, his victory marked by the obliteration of all human connection, save for his twinkle to you, the reader. Lando's refugees, in contrast, choose permanent bodily contact. I don't even see them as dead, really. Instead, they are transformed: prepared to tower above the maze of the future. Perhaps, one day, to crack its foundations.

Matt was the one who pointed out to me how many mazes are in this book. Lando's piece; Karn Piana's. “An exploration of the ways in which network technologies mediate our experience of each other and our surroundings.” Jacob Ciocci, formerly of Paper Rad -- the '00s' premier transubstantiators of media jetsam into peeled-open headspaces -- contributes a prose essay toward the end of the book in which he proffers, in three parts (which I will list out of order): (1) a benediction from the cultural savior that is the “Futuristic Artist”; (2) a criticism of the concept of the “Futuristic Artist” as an adroit monetization of ideas people can easily apprehend for themselves, giving lie to the myth of creativity and the construct of individuality; and (3) an autobiographically-styled sketch in which a character named “ME” describes his internet usage as communion with a Janus-like entity which can usurp power structures while, at the same time, trapping the user in constructed realities and toxic interrelations.

“However,” he writes, “every now and then I get lucky and all of a sudden I am lifted up out of the maze and am flying above it all.”

**

The terror of Mould Map 3, then, is the terror of options: of the necessity of change, and the uncertainty behind anyone's ability to guide it. I am reminded again of a Sammy Harkham anthology, this time 2011's Kramers Ergot 8, a book which all but palpably shuddered with anxiety and despair, surveying the path of comics with a regret born sadly of wisdom, and seeking, futilely, to imagine a future that won't merely reprise the ills of the past. It was comprehensively different from prior installments of that series, down to its physical characteristics: smaller in size; fewer artists; longer pieces.

The same is true for this book. Vols. 1 & 2 of Mould Map (“culture as the physical residue of civilisation and a virally exploding population,” per Frost) were 12- and 20-page pamphlets, 11.75” x 16.5” both, allowing no contributor more than two pages to deliver an image, a story fragment, a revelatory semi-fossil; anything. Editors Frost & Sadler drew inspiration from the zines and anthologies of Hendrik Hegray & Jonas Delaborde: Nazi Knife and False Flag, books of images which stood apart from the gnarled Gallic tradition of Le Dernier Cri by swapping out screen printing and other feats of hand-design for low-fidelity monochrome reproductions of color photographs and drawings that seemed less apocalyptic than severely drowsy. Frost & Sadler brought in heavy color as a unifying factor -- Mould Map 2 remains among the *loudest* comics I own -- but retained a scattered, enigmatic quality: easily dismissible, to be blunt, for those eager to have stories enunciated by their pictures.

Mould Map 3, however, adopts not the production characteristics of Kramers Ergot, or Nazi Knife, or LDC's pus-smeared Hopital Brut, but a properly mainstream Japanese art book: 8.25” x 11.75”, with heavy, glossy paper throughout (some exceptions apply). If you've ever bought anything luxurious from UDON Entertainment, particularly the anime/manga/gaming production art-flavored anthologies Robot or APPLE, you've basically seen Frost's & Sadler's approach here; even the 60 USD-ish suggested cover price is competitive with most of what you'll find on the applicable shelves of your local Kinokuniya. Where Mould Map 3 departs is in periodically inserting smaller booklets into the larger book -- a Le Dernier Cri trademark -- and marshaling all manner of attentive care after the reproduction of wildly varying visual approaches: some burning and fluorescent, others photographic, or heavy with slime.

In sum, it comes off as an attempt at a global address in as "normal" a format as its ambitions will allow – and for a book largely pre-sold through a crowdfunding campaign, there's probably a deliberate irony to that. Even the damn thing's asking price tends to vary from shop to shop, since almost everyone got their tightly-rationed supply on some backer's discount – and heaven knows little else in the bookshelf-comics realm leaves theoretical room for haggling.

**

Early on, as the Kickstarter began to pick up steam, I'd wondered if Mould Map 3 would constitute a focusing event for the British small-press scene, whereby the greater art-comics community would come together to help make something happen for editors/publishers mostly associated with UK collectives like Famicon Express – best known across the Atlantic for the 2012 PictureBox release DNA Failure, a severely odd package of fantasy genre rotgut seemingly exhumed from a self-publishing mass grave circa just past the b&w boom. I liked it, but it neither promised nor realized anything beyond tangential appeal.

Each and every contributor to DNA Failure are present in this book, and all of them present the best work I've seen from them. Of particular note is writer GHXYK2, who teams with Viktor Hachmang (a comics novice) for an upsetting vignette full of intense paranoia, in which a corporate spy Rohypnols himself and his coworkers as a means of isolating prime subjects for gene-splicing experiments. Throughout, Hachmang -- an avowed child of the European 'clear line' style -- obsessively focuses on architecture, technology, and small details of the human body, as if denying GHXYK2's characters recognizable humanity as an advance payment on the inhuman, company-dictated form they'll soon enough be adopting. It's marvelously creepy, redolent with a retro-future aesthetic spread so furtively that humankind has been practically devoured. I'm not sure whether the post-ligne claire Atomium artists would be thrilled or mortified - all the better!

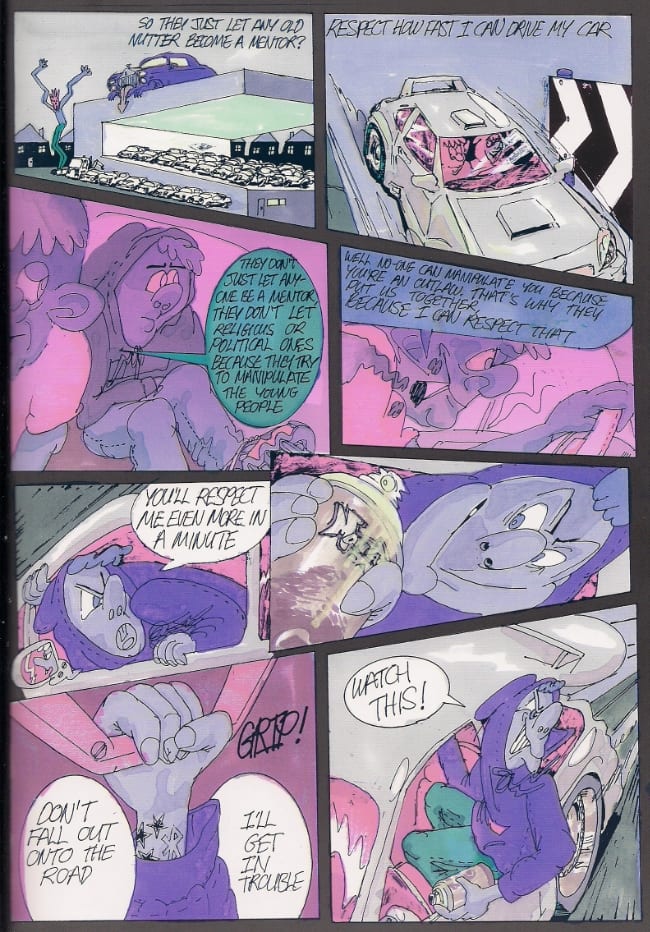

And then there's editors Frost & Sadler (or maybe just Sadler; the table of contents is frankly unclear) with a seriocomic pageant of youth-rebellion-as-playacting, in which a volunteer mentor zooms around with his hoodied charge spraying awful graffiti and lecturing poignantly on petty means of extracting added value out of the workaday life to which he is obviously tethered. “I could use my personal talents to help develop business solutions and stimulate growth, but they said it's not in my job description,” he laments, while the younger boy fantasizes about fleeing from cops who aren't around to stop him from practicing outlaw art which offers him no release from his assessment of career options. “If I'm really lucky, one day the arts council might allow me to do a legal mural on the youth centre portacabin!”

Likewise blinkered, they bond, and Sadler seems energized by their comedic exchange, squashing and stretching his goblin cast with new confidence.

Yet an ecumenical perfume wafts from Mould Map 3, under which various tribes and factions -- some of which, the aforementioned Lando included, are among the driving forces behind their own anthologies -- are united into a virtual tour of two floors' worth of Comic Arts Brooklyn. Look! Here's Noel Freibert of WEIRD magazine and the former Closed Caption Comics collective, oozing Barkeresque violence:

And here's C.F., a veritable grand old man of the scene in his mid-30s, touring a research facility for personal teleportation: trapping his human characters in boxes and mutating them as they try and escape. Bloody orange phenomena, barely beheld, are made luminous against the blue facts of the page like licks of flame off a disemboweled horse in Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise:

Jonas Delaborde himself makes an appearance, and less of an impression. Cerebral and rather chilly, he is nonetheless eager enough to be understood that his first of four pages -- depicting tiny blurbs of text, tightly gridded onto the page -- is captioned by additional text reading “Reshaping and reorganizing Rio de Janeiro 2014-2016 plan.” This explanation is followed by three additional pages juxtaposing flattened images of kites, resembling shields or crests or national flags, against snatches of text from an imagined future, or recollections of local history, or accounts of natural phenomena. Maybe there is some tension between appropriated and invented writing, I don't know. It is not very interesting as visual art, and, to the extent the sequence of its images suggest some narrative, it is ponderous and unrewarding.

But if, as I have said, placement in an anthology can be a type of confinement, an alternate option allows for strength in numbers: weaker works, which seem to applicably fit a book's theme, can find themselves verily elevated. Delaborde's chessboard Rio seems as much a maze as a scheme, eh? And his uncertain mass of narrative clips resembles a shambolic premonition of Ciocci's self-reflexivity! It is a critic's troublesome elective.

Still, I was more taken with Brenna Murphy's sculptural captures:

These are stuttering coughs of language like cities glimpsed from aircraft; culs-de-sac and open floors and sheer drops from glittering cliffs.

**

It can't be denied, however, that there is not-inconsiderable amount of weak material, sometimes in terms of basic presentation. Is, for example, the text running above and below the panels of Jonny Negron's submission supposed to blend illegibly into the hex map comprising its background? I can surmise arguments in the effect's favor -- something about revelations rising subconsciously from the mess of data that is discernment today -- but little could aid Negron's depiction of Nazi/Satanic cloaked envoys from religio-martial-political-science gesticulating on the internet and (I think) thereby inspiring observer resistance via weaponized meditation...? While the best of Negron's comics evoke the thrill of cool characters navigating terrains that seem ripped from a generational manga/video game dream, this is at best a half-story of clichéd signifiers, frozen as if on a computer screen, diminishing the visions of fleshy bodies that made this artist a Tumblr sensation.

Nonetheless, as with the Jonas Delaborde piece noted above, this stuff does find community in the Mould Map project: several isolated images throughout the book adopt a sloganeering vibe, dotting a page of elusive agitprop with #snowden and #nsa, say, or parodying motivational scale-the-peak posters with the image of a frozen corpse. Alone, they are clumsy enough to be mistaken for deliberate ambivalence, but parked like guideposts throughout the book these calls to arms seem equivocal and faintly condescending, and sometimes worse: I don't know whose idea it was to surround Aidan Koch's piece with Edward Snowden quotes, but paired with the artist's misty depictions of grids dotting natural landscapes and imprisoning human forms, the effect is explicative in a manner which suggests an outright discomfort with potentially abstract or elusive comics which I don't think anybody involved in this book actually has – so why muddy the aesthetic waters?

Koch is doubly troubled by the aforementioned Le Dernier Cri-type insert device, by which four of the book's contributors (to repeat) have their pieces reproduced as smaller booklets bound inside the larger confines of Mould Map 3. The little pages are printed in silvery tones. I can see how this shimmering effect might serve to enhance the delicacy of Koch's images for some readers, but I found it constrained by this reduction in size, its clarity troubled. Yuichi Yokoyama's typically energetic displays seem crammed in more ways than one – he's an artist whom I've never found to anthologize well, so reliant is his work on dozens and dozens of pages as an avenue to explore figurative animation. Left with a page count more in keeping with Tharg's Future Shocks than Travel renders him nearly incoherent. Sammy Harkham -- he of Kramers itself! -- at least, limits himself to jewel-box images of a cyborg woman undressing in a series of rooms and halls, descending finally to a subterranean lair and a more evil persona. It's titled “So Long,” and its tiny glimpses suggest the architecture of a house as the linearity of time, and shedding of garments as a discarding of emotional softness in the face of what's to come.

And then there's Dmitry Sergeev, the fourth booklet contributor and a creator of digital manga-style futanari illustrations: women with penises, who populate several full- or double-page illustrations. The brazenly titillating quality of these images contrasts sharply with everything else in the book, even those contributions ostensibly concerned with fantasy. Sam Alden, for example (full-size, in two colors), catches a rich girl daydreaming about defying her arid parents' bourgie art by getting into “really hoodrat shit” and toying with the idea of sex work. She fussily musses her hair in front of a mirror, pictures herself serving tea to a punk kid in a ruined building (she hates the taste of beer!), and makes certain to tell us that her house was designed with no two chairs facing each other: “Mostly they face either a window or one of the TVs.” Like Yokoyama, Alden tends to excel in longer pieces; lacking narrative dispersal, his work here underscores and italicizes every conceivable thematic gesture, to a suffocating degree. Sergeev's characters need no such overdetermined excuses to fuck and suck: they're just there to enjoy themselves, and only with them does the silvery effect of the short pages achieve excellent chromium applicability - the lone areas of pristine white on some of these pages are gobs of cum. They are perfect, plastic, mechanized joy.

**

If we want, we can look to the past as much as the future. It's not just the production on Mould Map 3 that suggests a Japanese approach, it's the cover, where the strokes of those eyelashes speak as plainly as the faux-logographic... logo graphic. This is manga from a western perspective, drawn by a Canadian artist: Julien Ceccaldi. And I hope I am not too bold in stating that the greatest legacy of manga's post-millennial boom in the U.S. and Canada is its lingering reminder that the social construct of comics-reading as a fast, consumable, popular form of entertainment centered on men and made, primarily, by men, was exactly that: a construct and an exclusion.

Ceccaldi also has a story inside the book; in fact, it starts on the very first page, its opening splash responding to the joyous, sparkling cover with moody indifference: surface vs. interior. All of its devices belie a profound familiarity with manga tropes, from the way shouting word balloons hang spiky in the air to the very font of the English lettering. His characters are muscular women with rock-hard abs, always exposed. “When I was eighteen,” the artist remarks, “it came to my attention how suspicious it is that the female body in manga is almost invariably young and thin, and often sexualized as such. As I grew older people couldn't understand that I saw myself in the skinny girls I'd been drawing since I was a child. They assumed I perved out on my drawings or something. So I began drawing women with sculpted bodies as a meeting point between where I come from and what I want.”

From this, we can see how expectations of female depiction frustrate everyone. The scenario is appropriately grim, catching an impulsive woman rushing out to meet an online date whose profile is her sole exposure to his personality. Soon alone and scared, the woman screams and cries, and rips the entrails from her belly as if in extreme gender performance. “Everything is going to be okay, sweet pea,” a maybe-hallucinatory friend remarks, “I know you didn't mean to be an insufferable person.” She is a character, in fact, trapped in a play with every line dictated, and the last we see of her is inside a banging club, in a Disney Princess's glass coffin: a dead Snow White, oblivious to a party surrounding her.

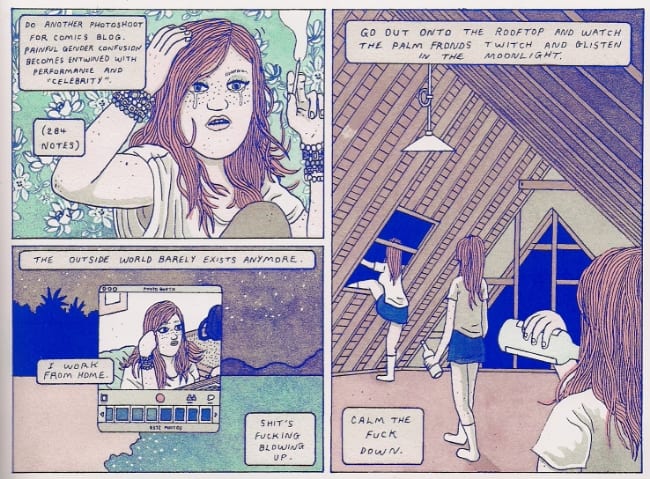

Simon Hanselmann is characteristically blunter. The first panel of his story depicts its protagonist dressed to the nines in pearls and stockings and a stripey little dress, his hard cock looming upward from his panties. Captions explain that the character has been getting high off decoration with feminine dress, fucked up and confused, “very over-aware of the leering skeleton beneath my flesh,” and fantasizing about going down on a girl he fancies: to be a proper “man” for her, he laments.

Hanselmann's Megg and Mogg comics often close in on characters' faces, but there is something especially fixated about the art here – an added dimension to the sole character's expressions. Frequently, he seems to be posing, glamorous and doomed, at one point literally in front of a mirror; obviously the artist expects much assumption of autobiography here, yet his character is specifically characterized as a performer, an in-quotes “celebrity,” awaiting a better future. The colorist is Lala Albert -- also the author of a solo piece elsewhere in the book, in which an androgynous apparition wields a plasm blanket in an effort to reintroduce a roomful of girls to the concept of “wetness” -- and everything she touches becomes faded and limited and slightly blown-out, as if the present has already been written off as dead by a person who needs some type of future to arrive goddamned fast, even if its promises are empty. What, pray tell, is the reward?

I note here that Hanselmann is also among the book's backers, their names listed on its final pages. Surrounding them are happy stock photos of readers; the type you'd see in a chintzy advertisement. The book's logo is plastered all over. So is the ISSN number. So are numerous slogans and mottos, looking arch and stiff and silly.

Then you look closer.

The language is comprised almost entirely of the editors' own art direction notes, straight off their Tumblr.

**

Weary, I capitulate now to the allure of the cage. The best of the Mould Map 3 contributors, I admit, manage to reconcile all of these concerns I've described so far: art, sex, flux, bodies, futures, puzzles, comics. I've made no secret of my opinion that Olivier Schrauwen is one of the most exciting cartoonists alive today, and his contribution here does nothing to disabuse me of that bias. Of a piece with his recent Greys and the continuing Arsène Schrauwen, this new work finds Armand Schrauwen -- another troubled twig off the artist's fictive family tree -- broadcasting his deepest ambitions from the bowels of 1986 into a homemade gadget that purportedly broadcasts his face across the sea of time. Alas, Schrauwen does not know that his broadcasts are, in fact, received, by a far-future bric-à-brac collector, transfixed by the strange fat man barking out of a screen but unable to manage any direct communication.

“You, who have found my machine, are a blonde woman with humongous tits,” cries Schrauwen, in utter despair. In fact, the collector is a doughy bald guy, apparently rich and explicitly gay. His friends and lovers speculate as to the origins of the talking box (a dude with a dinosaur head name-drops “Jon Baldasari,” one of several misspellings throughout the work which signal the fragility of either personal communication or editorial oversight), but the collector takes things more to heart, appropriating Schrauwen's dialogue for use in personal quarrels, and even seeking to eat the archaic, unhealthy foods on which the inventor subsides. As with all superior comics, an orgy soon erupts, with Schrauwen's talking head put atop a clown outfit and the collector dressing like a lady, both approximating human communication like lovers reaching for one another in an unlit room.

Obviously, in addition to being extremely fucking funny, this is a story about time and exchange. As with Alden's rebellious girl and (Frost/)Sadler's rude boys, the collector is a play-actor delighting in the preoccupation of other people's situations, but Schrauwen may have more of autobiographical plan. “[S]ometimes I try to communicate with my future self,” he's mused. “When I’m doing a boring task or making a boring walk, I’ll think 'In one hour I will think back at my past self here in this very moment.' Of course an hour later when I’m relaxing, released of my boring task or walk I never think back to my past self.”

There is nothing you can do. Schrauwen is like Ceccaldi's gutted heroine, sealed in glass while life ruts with vigor. Is this cartooning – drawing long, slow narratives for swift consumption in the far future? Is this art – the communication of meaning without control over its receipt? Is this Mould Map 3 – an experimental address, which, barring re-contextualization of its component parts on the internet or some future publication, is limited in reach to mainly the devout backers of its fund-raising campaign? Collectors, whispering of values among themselves, and then leaving to do something else? When was this book released? Two weeks ago? 1987? What's the point of reviewing it? What's the fucking point, but to talk of artists?

Ambivalence reigns. I return to Blaise Larmee.

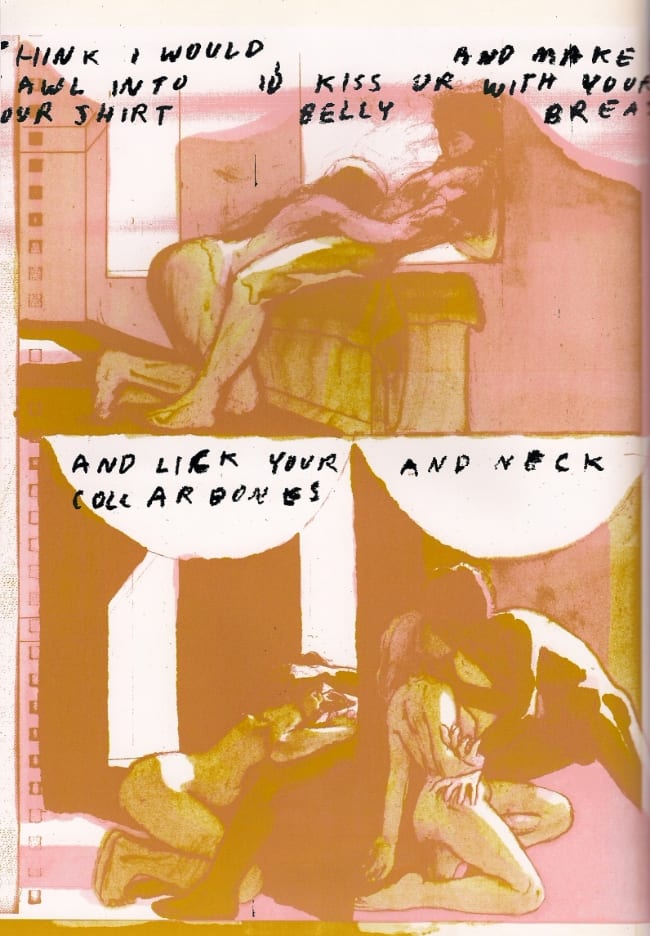

There are five pages of Blaise Larmee art in this book, and they are wonderful. The first has four layers of information crammed together: (1) a handwritten note from Larmee to editors Frost & Sadler, explaining that the preview images he'd sent them “failed to become narrative,” and that he was instead attaching images with text drawn from a Skype session with a Tumblr follower; (2) below that, four tiny panels of character drawings, possible the preview images, although they quite clearly depict a narrative, if only that of a familiar Larmee cutie pie character performing waves and tumbles; (3) beneath that, an abstract image suggesting bodies and fluids, one face visible; and (4) running down the left hand side, text taken or transcribed from a chat session. The content is sexual.

The remaining four pages reprise the look of (3), though bodies are now clearly discernible. They are engaged in erotic and intimate acts. Above these images, two tiers per page, is text presumably taken/transcribed from the same chat session as (4), but written out in the same style as (1), sometimes running off the edge of the page into oblivion. It does not exactly correspond with what the images are showing, but then...

And if we are to believe Larmee on page 1, this is not sex that physically happened; it was facilitated by communications technology, over the internet. Yet the tenuousness of Larmee's handwriting combines with the indistinct outlines of his and his partner's coupling bodies to suggest the tangibility of recollection. Physicality is fleeting. Remove the physicality, but retain the signal of sex, and in later days isn't it something that happened, imagination flowing into memory, inseparable, touch and thought in proximity like words and pictures? What do you want from it? The future?

What do you want to be?