The way Drew Friedman bridges the gap between portraiture and caricature is not unlike a skilled cartoonist working in a naturalistic style who draws a car that bends when going around a turn. It's not "realistic" in the strictest sense of the term, but it feels more real in the context of the page. As Karen Green notes in her introduction to Friedman's new book More Heroes Of The Comics, Friedman's drawings of people imbue them with soul instead of simply laying there on the page. Tiny flourishes, visual in-jokes, and a painstaking attention to the right details give each portrait of a figure from comics history a visceral, almost animated quality. With supporting biographical text on the page opposite each portrait, Friedman's mission in this book is to deepen and broaden the reader's understanding of comics history, highlighting obscure figures as well as more familiar ones.

The title of this two-book series is more than a little tongue-in-cheek, as is the book's logo with a lightning bolt under the word "heroes." Friedman contrasts the fantastic qualities of the comics with the mundane images of the men (mostly) who created them. At the same time, that gesture is not so much one of gentle mockery but rather of deep respect from one craftsman to another. Friedman sought out photographs of the artists and writers at their desks and drawing tables whenever possible, because he wanted to record and celebrate the hard work that the artists performed to create the comics that he loved so much as a child and continues to love now as an artist. It's also why Friedman tried to capture the artists in their later years when he couldn't get them at their drawing tables, because in a culture that obsesses over youth and the new big thing, he wanted to honor those artists who continued to ply their craft well into old age. The wrinkles and liver spots that he used here and in his Old Jewish Comedians series of books aren't meant to demean the artists, but rather celebrate their reality.

In many respects, More Heroes Of The Comics is more in line with Friedman's traditional interest in b-grade, obscure, and discarded American culture than the first volume. That first book, which had 83 illustration plates, included Friedman's heroes from EC Comics and a number of obvious choices like Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Bob Kane, etc. He threw in a few more obscure choices in an effort to make the book more than a line-up of dead white men, but the history lessons came more from Friedman's visual interpretation of each artist through his portrait/caricature than via the accompanying text, even if Friedman took great pains to have his biographical copy reflect the controversies that might have surround each subject, especially with regard to issues like exploitation. In this new book, Friedman tackles one hundred subjects, and has the luxury to go in some offbeat directions.

For example, the Three Stooges-obsessed Friedman includes Norman Maurer, a cartoonist who happened to marry Joan Howard, the daughter of Moe. A couple of years later, he wrote and drew the first Three Stooges comic book (featuring Friedman favorite Shemp) and later worked on early 3D comics, including the Three Stooges in 3D. Maurer's portrait is a profile shot at his drawing desk of an unassuming young man with the typically slicked-back hair of the era. Also featured in the book are Hy and Bill Vigoda, brothers of the well-known actor (and another Friedman favorite) Abe. They are featured not just because of Friedman's fan interests, but rather because they represent something that Friedman repeatedly makes a point of emphasizing: people who worked in the industry for a long time, on comics that aren't lionized today in the same way that popular culture has seized upon superheroes. The Vigodas, for example, after working in some of the early comics sweatshops, went on to long careers working in Archie comics.

His portrait of Bob Oksner is another good example of this. He worked at DC Comics for years, on the celebrity-themed comics they used to pulbish, like The Adventures Of Jerry Lewis and Sgt. Bilko. Dell and Gold Key churned out thousands of comics thanks to the likes of Chase Craig, Gaylord Dubois (a charming portrait of the writer grinning on his couch), Al McWilliams, Paul Norris, Dan Spiegle, and editor Oskar LeBeck. They all get their due from Friedman here, as well as Dell's long-running anthology Four Color. While many of these comics are forgettable, they were published for decades and certainly had their audience, much like the romance comics of the forties through sixties did. Friedman also draws portraits of Archie stalwarts like Dan DeCarlo (from a robust youthful photo where he looks filled with spirit and vigor), Bob Bolling, and Stan Goldberg.

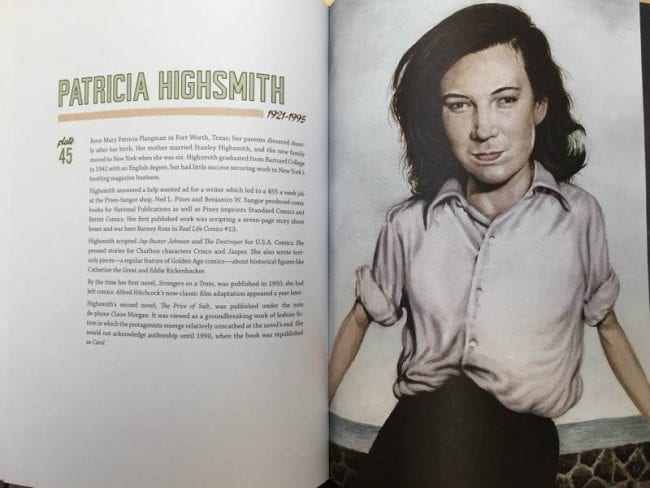

Friedman devotes room to devote to a number of comics dabblers, which allows him to tell the stories of a number of women. They include Olive Bailey, who did a comics version of a childrens' book series called Land of the Lost; Audrey Blum, who worked in the early sweatshops; and Patricia Highsmith, who worked briefly in comics before she became famous for writing novels such as Strangers On a Train. One of Friedman's specialties is capturing the wrinkles and folds in clothing, and he's especially spot-on in that regard with women's clothing. Blum is stylish in her pose, though her side-eye expression perhaps indicates a certain mischievous quality. Highsmith's pose is sort of casually butch, with her sleeves rolled up and a tight-lipped, enigmatic smile on her face.

Other dabblers include Ray Bradbury, many of whose stories were adapted by EC Comics writers (at first without his permission), Mickey Spillane (who wrote scripts at rapid speed before tiring of superheroes), Harry Harrison (another scripter turned science fiction writer) and Doug Wildey (who started at Dell and later created Jonny Quest). The most fascinating is Orrin C. Evans, a journalist who published All-Negro Comics #1 in 1947, all of whose contributors were African-American. A second issue wasn't published because vendors refused to sell it. Jules Feiffer has a similarly enigmatic half-grin on his face, and Friedman went to town in drawing both the design and the folds on his black-and-gray checked shirt.

Friedman pays tribute to the craftsmen behind the scenes, like Ben Oda (one of two Asian-American cartoonists depicted in the book) and his iconic lettering and logo designs for EC Comics; Jack Adler, who did the color separations for Action Comics #1 and created countless beautiful-looking covers because of his painstaking techniques; and Ira Schnapp, who created a number of DC's logos. Friedman's portrait of Curt Swan is remarkable because of the sheer joy on Swan's face as he draws his long-running assignment in Superman. Bob Kane's Batman ghost artists Win Mortimer, Jack Burnley, and Shelly Moldoff are also featured as part of Friedman's interest in making sure the record in his books reflects their achievements.

In some respects, the publishers are the most larger-than-life figures in the book. DC/National publisher Jack Liebowitz wears a fedora and a shit-eating grin at the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade with a Superman float going by. Considering the way he and fellow publisher Harry Donenfeld exploited Superman's creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, it's no wonder that he looks like he got away with a crime. Then there's Victor Fox, who got sued by DC after publishing the adventures of Wonder Man in Wonder Comics. The self-proclaimed "king of comics" is here captured in his office as a rotund man with a fedora, glasses, an ill-fitting suit, and a cigar that seemed to be useful for gestrual emphasis as it is for smoking. Ian Ballantine is another subject here; his ballsy career moves almost single-handedly created the paperback market, which was crucial in keeping Mad's influence going beyond just its magazine form.

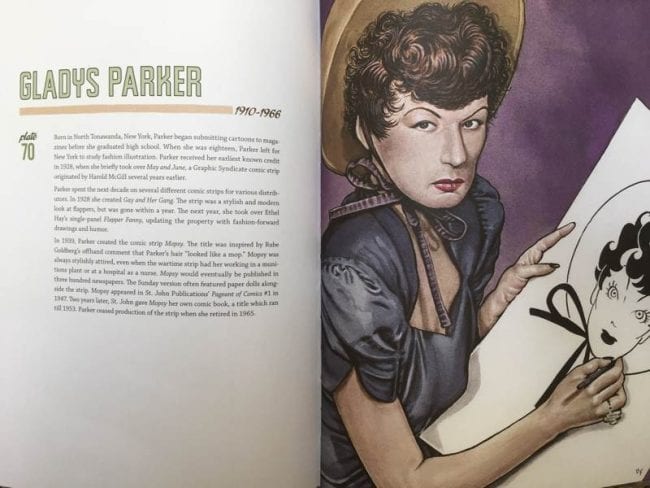

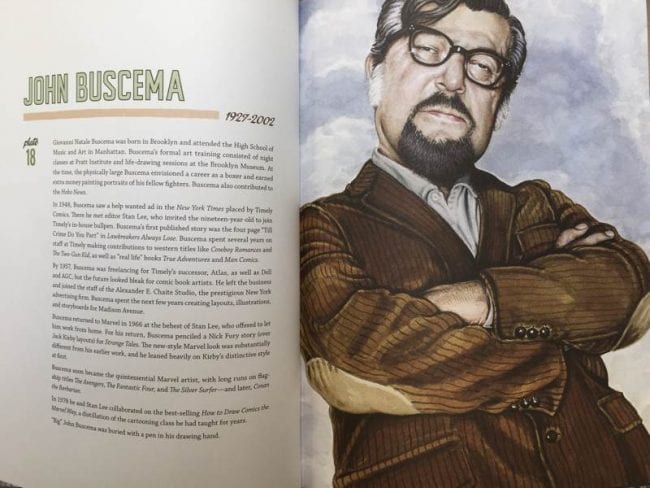

The best Friedman portraits are the ones that lean on caricature just a little, as he subtly draws connections between artist and subject matter. For example, the portrait of a beefy John Buscema with a scowl on his face and his arms folded is not unlike a pose that Buscema no doubt drew countless times on his favorite character, Conan the Barbarian. Russ Manning's slender but muscular frame echoes that of Tarzan, whom he drew for years. Gladys Parker's portrait shows her drawing the character created in her own likeness, Mopsy. It is hilarious because she's wearing a cowboy hat (as is her character), but her expression seems to betray that this was a staged photo that she was not especially thrilled to participate in. Pin-up king Bill Ward is depicted at his table with a shaggy beard and a spiked leather wristband, drawing one of his typically leggy models. Finally, there's Bob Wood, whose own shady life paralleled the series he helped to create, Crime Does Not Pay, with a rap sheet including manslaughter (that could have been decreed a murder), gambling, and out-of-control drinking. His battered visage is depicted by Friedman as one of the subjects of Wood's own comic. It's emblematic of a book that takes the reader down comics history's back rooms, side alleys and forgotten paths, giving each subject the same amount of respect and attention and asking the reader to do the same.