There's more to this one than most comics - more high points, more flaws, more time in the making, more lines on the page. In this respect, it must be counted a success. Since his ornately embellished Conan run at Marvel in the early '70s, Barry Windsor-Smith has been resisting his art form's instinctive reach for simplicity, and making comics with more. Half a century later the process peaks with Monsters, a massive tome intent on more intensity, more realism, more grandeur, a mixing of the stuff of life with baroque and overwhelming dread.

Despite the deep focus his artwork strives for, Windsor-Smith feels less intent on presenting the specifics of his narrative than its tone - one most often sumptuously gloomy. How Monsters hangs together as a plot, I think, is less important than the feeling passed on to its readers as they push slowly through hundreds of densely gridded, intricately drafted, balloon laden pages. I myself found it an overpowering experience of simultaneous disquiet and awe. The mood that Windsor-Smith summons in Monsters is simply more intense, more impactful... more... than all but a few other comics are capable of.

In Monsters, Windsor-Smith oars readers backwards in time over two decades of his characters' post-WWII family history, showing the shreds of lives destroyed after generational traumas have exploded, then sifting obsessively through the details of time's passage to watch the blasts themselves. This cycle is repeated again and again as the story tracks back across the generations - it feels a bit like unpacking a ghastly Russian doll - and every trauma's root in a previous one is illustrated exhaustively. You could follow the line of narrative Windsor-Smith sketches out here endlessly, back to the caves, and such is the unsavory pleasure in feeling the trap door drop away with every rewind of the book's chronology, in seeing things get worse the further back you go, that in a sick way it's easy to wish it would go on forever. It does go on at great length, and stops only after reaching such a frothing pitch of upset that any more might tip it into farce. Better to leave off on the highest peak, twisting in the wind, than jump.

Through the darkness, it isn't particularly tough to see the Incredible Hulk story Monsters was first imagined as back in the '80s poking through to the surface; ditto the Captain America comic it at some point became and unbecame. Its similarities to Weapon X, Windsor-Smith's detached body horror take on Wolverine's origin, are so great this book could take place in that one's Marvel Universe with a few names changed here and there. The elevator pitch for both books is identical: a vulnerable man is taken from the fringes of society into the annihilating arms of America's Cold War-era military industrial complex, where a series of medical experiments reduce him to a deformed body that posses the merest flicker of humanity, as likely to gutter and die as to endure. Weapon X is a tightly focused book, going to tortuous lengths to confront superhero readers with their favorite genre's fetishistic emphasis on physical pain and bodily destruction. Monsters features much of both, but also has an epic's sprawl, sinking deep into Weapon X's emotional core - a kind of melancholy sadism - and how such feelings come about. It reads like work from the heart of a committed pessimist who has not abandoned himself to nihilism; from a pacifist whose belief that military force destroys everything it touches comes with an intimate understanding of just how total that destruction can be.

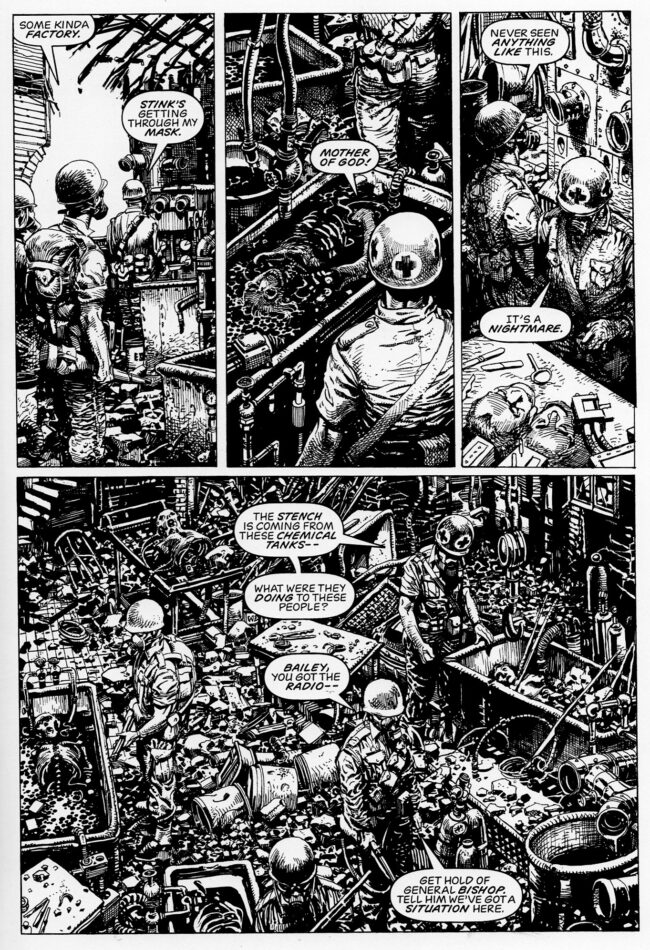

In Monsters, Wolverine is mercifully swapped out for Tom Bailey, an American GI whose unit discovers a top secret Nazi medical installation in the final days of the war. Like most characters in this book, Bailey possesses a slight psychic sensitivity, and his encounter with a place that's seen the horror this one has delays his return home by four long years, as Uncle Sam pieces both Nazi super-science and Bailey's sanity back together. Bailey's wife Janet and son Bobby endure a communication blackout over Tom's long convalescence, with a military attache's clandestine updates and wooings of Janet doing as much harm as good. But Janet and Bobby's true suffering begins when Tom returns home as an abusive, post-traumatic shadow of his former self. Bailey's increasingly violent behavior crests during a Thanksgiving dinner that Windsor-Smith returns to again and again, slicing it apart to play out agonizingly over the length of the entire book. Fifteen years later young Bobby Bailey, a disabled vagrant abandoned by the world, applies for the Army and delivers himself into the jaws of the same medical experiment his father first uncovered, now resurrected to serve the cause of freedom. With little of Bobby's spirit left to destroy, the project destroys his body, as two men with connections to Tom Bailey's old unit make a doomed attempt to save him.

And that's the short version! It's a winding comic booky plot with plenty of cloak and dagger, twists in the action, and assurances that things are Not As They Seem, and it's got a genre comic's reflexive shifts into the supernatural and science fictional when literary realism can’t provide the bite that's needed. But this material is elevated above the mass of genre comics by that realism, and its creator's formidable skill. Monsters feels like nothing so much as a comics version of Stephen King at the height of his prime - obsessed with both the vivid mundanity of midcentury suburban life and world-shaking powers that lie beyond the pale, fascinated by minor characters and protagonists alike, prone to lengthy anecdotes that seem disconnected from any forward narrative momentum until you realize they've just provided a big jolt of it. Windsor-Smith's art, full of little subtleties, meticulous about gesture and facial expression, wrapped in webs of densely crosshatched light and shade, is a perfect match for his story. The uncountable ink lines in every panel sometimes feel like their creator's attempt to slice into his protagonists' inner workings as much as shape their outer forms.

However, Monsters' backward-running structure frees it from the sentimental optimism about humanity that drags down much of King. There is no hope here because there's nothing to hope for - we've already seen how badly things turn out for everyone. Windsor-Smith's writing is merciless, forcing readers to watch the slow unraveling of scenes whose tragic endings have already been well established, filling up densely paneled pages with back and forth dialogue exchanges that hurt the characters and make the readers feel it. Scenes of heartbreak, deception, and paranoia spread over beautiful drawings whose grace of composition keeps you from noticing how painful the stuff is to push through until each set piece concludes. The sustained focus here, the unwillingness to turn away from a scene as it unfolds - even for what at points could be increased dramatic effect - is astonishing, and cruel. While filmed scenes of the domestic abuse this book revolves around might be more immediate, what Windsor-Smith does here is agonizing - mounting scenes of sadism and despair that go on and on, forcing readers to animate them in the slow motion it takes to piece together narrative from word balloons and drawings. This book both rewards marathon reading and begs to be put down for a breath between its chapters.

All this said, Monsters is not so much a work of horror as a work of noir. It features ordinary people battling their own worst impulses and shattered mental health on a menacing American homefront post-WWII, marching out of formation toward unsettlingly imaginative dooms - slotting Windsor-Smith's story in comfortably with the dime novel canon of Jim Thompson, David Goodis, and Fredric Brown. But where the great men of noir trained pinpoint spotlights on sick or raging heroes, leaving the audience to piece together the smithereens left in their wakes, the more empathetic Windsor-Smith insists upon centering the social existence of his antisocial antiheroes. Family disintegration is Monsters' true topic, and both Tom Bailey - a noir protagonist in full - and Elias McFarland, the Army sergeant who gives his sanity and life to save Tom's son Bobby - are set aside for most of the book in favor of their wives and children.

Windsor-Smith mounts compelling scenes of Elias cooped up in his basement taking scissors to his collection of Golden Age comics, or Tom plotting violent vengeance on the men who comforted his wife during his war. But these passages are there to take us deeper, to show how the men's dances on the threshold of their minds leave their families at thresholds far more real - abandoned by their breadwinners and traumatized by their behavior, left to the mercy of a society with just this side of nothing to offer them. Slowly, Janet Bailey emerges as Monsters' real main character, a desperate, determined woman dumped into a nightmare no self-sacrifice can stop from playing out.

Her counterpoint is Friedrich, the villain of the piece, a Nazi whose machinations destroy two generations of both the Bailey and McFarland families. Friedrich's wartime "secret origin" provides Monsters' climax, as Windsor-Smith cuts from the Bailey clan's tragic final moments back to the pure, black horror of the war's last days in a scene-to-scene transition more harrowing than any I have seen in comics. Like Roberto Bolano before him, Windsor-Smith renders the war as the crescendo of the European gothic horror tradition, the last and biggest evil thing to happen in those black forests full of spirits and beasts. The lavish, sickening set piece Windsor-Smith choreographs is as compelling a vision of hell as any Renaissance painter's. Friedrich bounces off its walls nearly crackling with malign energy, a twisted dwarf or sprite as purely evil as any comics villain to have come before him, slipping backward and forward in time, pushing the book's content to truly shocking extremes. It's easy to imagine that Monsters by its end may simply be too much for some - the length, the grinding slowness, the sudden blooms of violence and atrocity - but there are riches to be had in every shovelful of loam.

The book's finale is a letdown, circling back from the beginning to the end of its timeline. More metaphysics than the previous 300 pages contain are marshaled to provide a note of uplift that doesn't quite cohere - and in any case is unconvincing immediately after some of the more disturbing comics in recent memory. It's not a mortal sin that the ending doesn't make the same inexorable kind of sense as the rest of the book - in a story about the supernatural, making too much sense also makes every narrative move seem predetermined - but a feeling of the eerie and the unexplainable is missing, and what is there is somewhat pat.

The lax finish is not a fatal error - even a catastrophically bad one could only mar what comes before so much - but it feels like a misstep because even in the bleakest passages of an extraordinarily dark book, Windsor-Smith mixes in some powerful rays of light. The first action sequence is a car chase so high-impact and well blocked that you'll forget there aren't more of these in comics because they're so hard to pull off. A blink-and-you'll-miss-it page of the abandoned Janet Bailey masturbating underneath her overalls as wind buffets her bedroom's curtains has more eroticism to it than any explicit nude scene. A long dialogue sequence centered on the proper use of a potato gun is pure vaudeville, a comedic digression as completely unexpected as any plot twist, getting more and more laugh-out-loud funny with every line. A silent page of Tom Bailey picking his teeth and smoking in undershirt and stirrup socks, the nine-panel grid zooming out to reveal him on the toilet pinching off a shit, is immensely satisfying. Windsor-Smith has a natural ear for the rhythm of conversation, and reading his dialogue unspool without much concern for hastening the plot is a true pleasure, one that's too tough to find in comics. A few more touches of levity and speed might have erased any need for Monsters' flawed finale.

And the art! It's difficult to overstate how much work visibly went into the creation of this book, but easy enough to see how Windsor-Smith spent a few decades at the drawing table on it. These images are marked up and hyper-detailed in the extreme, but never feel overdone or stiff. Windsor-Smith is perhaps the only artist to have come up in the American superhero mainstream whose devotion to crosshatching hides no gaps in drawing skill. Perspective, the figure, gradations of light and shade, facial expressions, panel composition, drapery, line weight, the blocking of action... there isn't a noticeable blip in quality in any of it the whole book through, all the more impressive given the insane amount of labor in its creator's approach. Every page is a clinic. It commends Windsor-Smith's writing that you can move through the story at pace without getting bogged down looking at the pictures, thanks to the lively plot. But open to a random page and you can spend as long as you like picking these gorgeous drawings apart line by endless line.

There's more, of course - so much more that it's impossible not to forget about a few standout scenes or knife-twisting subplots until they pop up on your next reread. Due to this exhaustive overstuffing as much as its deflated ending and some looser narrative threads, Monsters misses out on being a masterwork by the skin of its teeth. Yet what it is may be more interesting - the kind of immersive, flawed experience that leaves readers on the edge of total comprehension, eager to dive right back in and decipher what they missed. It's the kind of book that gets better with each rereading - the sci-fi elements are just extraneous enough, and the stark reality of the way the characters talk and move and hurt each other is only more affecting when you know what's coming. In a recent interview with NPR, Windsor-Smith said "I created characters... whose personalities began to take over the story. I had to have faith that their wishes and desires were the key." As the pages melt away with each rereading, I'm struck by the high drama of this quote: an author ceding control of his work to figures so tragic, so malevolent, must have been an hellish task indeed. I have a feeling I'll be picking apart those wishes and desires for years to come, both with the book in front of me once more and in my idle moments. I suspect I'm not the only one.