The critic Matthias Wivel has noted that he finds the Monsieur Jean comics of Philippe Dupuy and Charles Berberian to be bourgeois and dismisses the most recent volumes as "snoozers." There's something to be said for this point of view, especially in the stand-alone volume The Singles Theory. The most traumatic thing that happens in this volume is that Jean's best friend Felix is forced to live with him after he gets kicked out by a now ex-girlfriend. The duo drink, eat, go to parties, hit on women, and make witty remarks to each other. In other words, there's not exactly a lot at stake here, and even the conflicts and crises that pop up in the book feel like the proverbial tempest in a teapot. They're "first-world problems," essentially, adding a bit of resistance to a book filled with quiet, slice-of-life humor. Whether or not someone identifies with this particular slice obviously varies.

That said, the Monsieur Jean comics remind me of Kim Thompson's 13-year-old plea that "more crap is what we need." What Thompson meant is that comics would benefit from more middle-of-the-road and "safe" material for general audiences that is nonetheless created with care and skill. Dupuy and Berberian's stories about a writer who has to deal with aging, career, relationships, and (eventually) children are breezy, fun, and relentlessly clever. Neither artist is someone I'd put the same category as Joann Sfar, David B, or Lewis Trondheim in terms of being an innovator or forward thinker. Instead, they are both superior craftsmen who are well-schooled in the clear-line tradition of Franco-Belgian comics and possessed of a certain illustrative flair. With this edition's duo-tone blue wash, the end result is a slick and attractive package that nonetheless is remarkable for its genuine warmth and affection for its characters.

What distinguishes this book from the typical slice-of-life indy book is Dupuy & Berberian's sharp sense of comic timing. Their ability to transition from the minutia of daily life to setting up a gag or routine is seamless, with the best example in the book being the short story "A Birthday Party In The Countryside". Beyond capturing that unmistakable experience of being invited to a party where one knows almost no one, and being held hostage because your ride doesn't want to leave, the story turns on a dime into slapstick and the humor of awkwardness. There's a parallel narrative in this story about a couple who are forced to take the train out to the country in order to attend the party, as they bemoan that they, "real friends" of the birthday girl, weren't chosen to go along in that car. They wind up missing their stop, getting off far away, missing taxis, and getting soaked during transit. When they finally arrive, the car carrying Jean and his friends is making its way out. When the trio of Jean's friends start bitching to each other about how boring the party is, the birthday girl pops up whining that she's afraid people will leave the party because it's boring. On cue, the trio starts dancing. The story also has flourishes like Jean's flights of fancy, wherein he imagines the birthday girl as a jailer forever keeping him imprisoned in a tower of boredom.

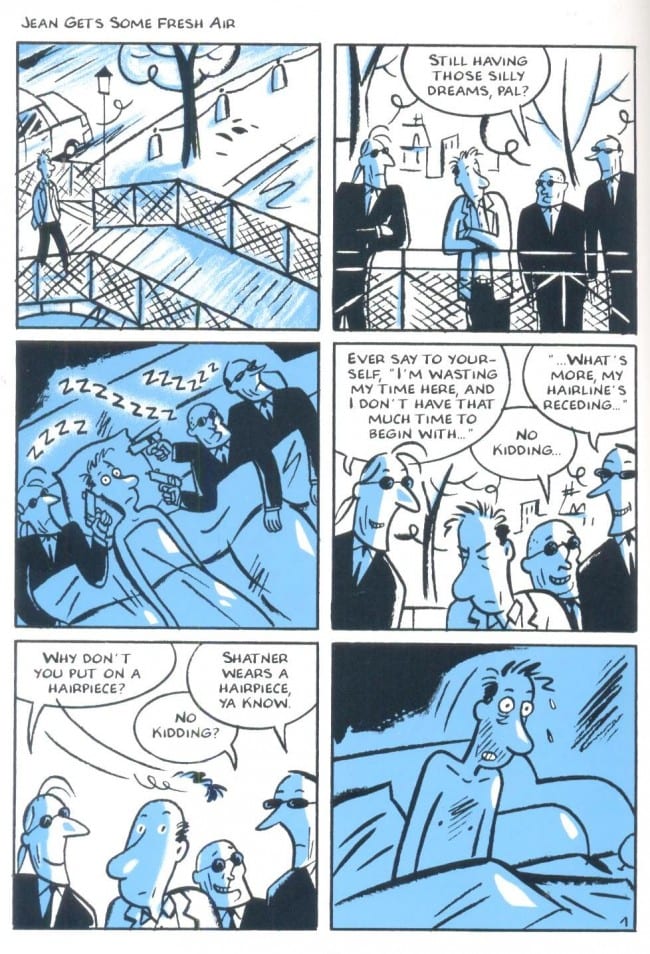

The book is stronger when it focuses on Jean instead of his perpetually kvetching friend Felix. Felix whines about being single and whines about relationships; in the story "Playing Hooky", he's very much a man-child in a way that's embarrassing to observe. While, in his own way Jean is as obsessed with sex as Felix, he's also a creative force who spends much of the book trying to get past his writer's block. Indeed, the highlight of this story features Jean getting ambushed in a TV interview about the whys and wherefores of writer's block by an idiotic TV personality who hasn't even read his book. Jean is haunted by dreams of an elite squad of assassins that's come to execute him, only to be granted a stay of execution for the most ridiculous of reasons (like seeing his favorite movie or taking a bath). He's freed of that particular burden at the end of the collection, after he's managed to accidentally kill the annoying, yappy dog of his future mother-in-law but is able to get away with it. There's an elegance with which Dupuy & Berberian manipulate the story's mechanics to achieve maximum discomfort and humor. The flecks of sweat pouring off Jean's brow when he admits to his fiance that he's killed the dog by sitting on it emphasize the ways in which he has to conspire to find ways to keep sitting on the couch until everyone else has lift. When the duo is trying to find a way to dispose of the dog (drawn as a solid black mass of squiggles), we see the characters only in silhouette as they break up laughing thanks to the ridiculousness of it all.

If there was a single story that captured the essence of the character and his world, it's "The Upstairs Neighbor". Every night, Jean and his girlfriend are kept awake by the upstairs neighbor's extremely loud sex ... which seems to somehow incorporate a toaster into the proceedings. The sound effects used ("RAAHAHHARGL RRRRR AAAAAAHH RAAAAAA RRRRRR ZDOING ZDOING") add a lot to the humor, even as it's deliberately baffling as to what the neighbor is doing. There's another delicious moment of discomfort when Jean brings the neighbor over to demonstrate that his bedroom is an echo chamber for the frolics from upstairs, and that leads to Jean discovering the toaster in the trash. He and his girlfriend grab the toaster, and the final panel shows them with eyes wide open as they sit up in bed, with no idea of what to do. That bemused look at the end of a gag revolving around something both slightly absurd and entirely familiar is the encapsulation of Jean: an artist negotiating his way through a ridiculous world that is not without its pleasures. Dupuy & Berberian's ability to communicate those pleasures is why it's worth spending time in this world.