The hook for Mike Freiheit's minicomics series Monkey Chef is a strong one: it's an account of time spent in South Africa, preparing food for monkeys at a sanctuary, as well as cooking food for the humans who worked there. A more conventional version of this story would be just a straight journal comic; the sheer novelty of the experience might have made it worthwhile in that form. However, Freiheit's approach is a more artful one, juxtaposing different events against each other in interesting ways. That said, the story is a fairly straightforward but episodic series of anecdotes and observations about his experiences that doesn't set out to make him look good. As Freiheit demonstrates, his time spent in South Africa was the epitome of a difficult but worthwhile experience.

The opening scenes of the first issue reveal a shadowy, naturalistic style that Freiheit uses throughout the series for nature scenes. His figure drawings are a lot looser and spontaneous, which makes sense because despite the remote location, the series is all about relationships. Still, there are often one- or two-page spreads that show off Freiheit's nice brushwork, made all the more distinctive by the dark blue wash chosen for the comic. A panel detailing a sandwich he got in Amsterdam in the early going is a marker for just how important a role food is going to play in the story.

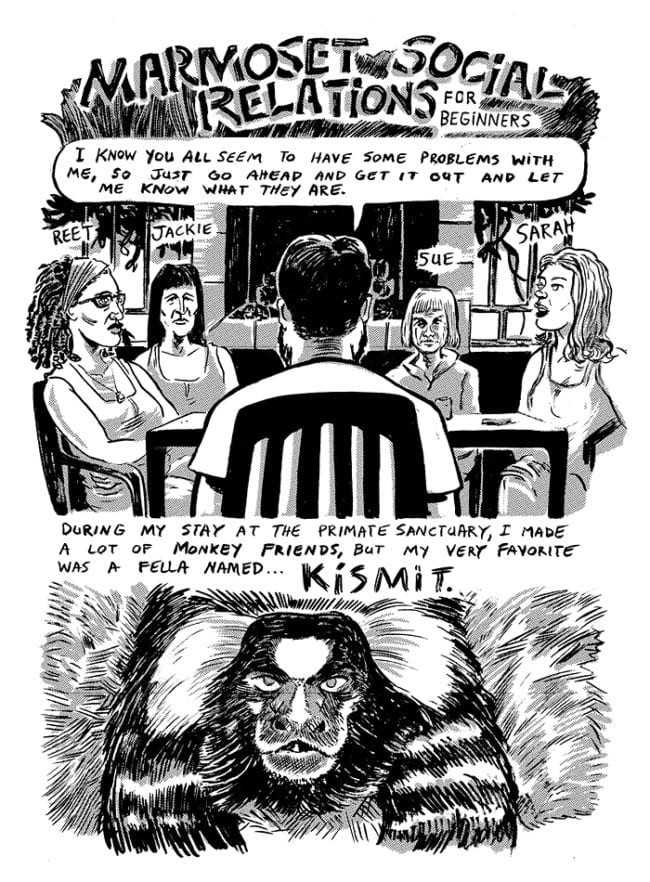

After that early setup, the first major story zips ahead in time and tells the story of a marmoset that got loose and how Freiheit got a nasty bite catching it. This, and a fanciful story imagining an entire mythology around the frogs that kept getting into his closet, are both relatively conventional anecdotes that establish character and setting. The third story, "Marmoset Social Relationships", stands apart from the others in its complexity and ambition. Freiheit goes back and forth between an air-clearing but difficult discussion with his co-workers about interpersonal tensions and the story of a monkey named Kismit, who had his own difficulties in getting along.

Freiheit doesn't get too cute or heavy-handed with the comparisons, simply letting each narrative play out naturally while shifting back and forth. Freiheit doesn't hold back or try to make himself look good in the argument, though he does reveal the things he though while trying to listen to and accommodate his co-workers. His drawings of the event are clever, as the lecture he gets from one co-worker on how to feed grapes to the monkey is drawn as though he is a toddler in a small chair and she is towering over him. Meanwhile, he details Kismit's story of not getting along with his "roommate," being placed with another monkey and battling health problems. The whole discussion is set into motion because Freiheit has tired of his co-workers talking behind his back, a clear contrast with the ways in which Kismit directly confronts those he has problems with. In the last panel, Freiheit has placed Kismit in a new cage, thinking, "I hope he learned his lesson," a deliberately ironic thought.

The second issue focuses on a single narrative that ties together some of the daily minutia of his job as a chef, like the (subpar) tools he uses and the precise sizes he has to cut up food for each different type of monkey, and uses them in a larger, darker story about a co-worker named Michael. Michael is a Zimbabwean refugee who is constantly being triggered by his PTSD and possibly other mental ailments, thinking people were out to kill him and starting to hear voices. Freiheit details the kind of work that Michael does in maintaining monkey pens and other construction work even as he reaches out to him as a friend. .

This volume tells a complete story about Michael, including his eventual and sudden departure from the sanctuary. While he is paranoid about danger, he isn't wrong that his presence makes people feel uneasy, and he can sense the tension. The detours into quotidian life that Freiheit describes are both a way of breaking that tension (a sort of narrative palate-cleanser) and a way of providing information for the reader about just what is done at the sanctuary. As someone who loves food and enjoys cooking, the bland palates of his co-workers are clearly frustrating to him, just as their interest in generic pop culture inhibits his desire to spend time with them. In the first issue, one of his co-workers calls him out for being arrogant, and she isn't wrong. That said, the issue is less one of arrogance than of isolation, as he clearly misses making connections related to his interests.

This issue is in black & white and doesn't look nearly as sharp as the single tone wash from the first volume. I imagine when the entire series is collected, that will be fixed. I'll be curious to see what other directions Freiheit explores, especially with regard to thinking about the people who were around him and discovering their stories. Simply being at the sanctuary would be an unusual life move for anyone, and I hope Freiheit will be able to integrate all of these stories into his larger narrative.