You get all the way to page 130 in the new collection of Blutch's Mitchum from New York Review Comics before a character actually says "Don't be afraid...we just want to look." But by then the book's obsession—there will prove no better word—with the thrill and chill of seeing and being seen, especially when one end of the operation is male and the other is female, is clear. When it arrives, during the course of issue Numéro 4, the statement is made by a masculine ogre, one of Blutch's sexually charged figures of coiling black ink, which give the impression of seeping up from petroleum seams underneath the paper. Apparently naked apart from a sailor cap, he and a group of similar hulks have disrobed a mute female dancer, now hoisted off the ground in an aggressive caress. In the background, another of these trolls has already put on the dress that she was wearing, and by the next page he's the one doing the dancing, having appropriated the grace and eroticism he presumably saw in her—not very convincingly by the look of it. The only sign left of the woman is a bare leg sticking into the frame, the rest of her obscured, prone on the floor. A painter now materializes to record it all, although this artist is no human but a chimpanzee, so its instincts in this sexually charged conflict must be of the animal variety. The sequence is somewhere between an attack of the night terrors and a BDSM reverie; but is it the dream of the dancer, the brute or the reader?

Squirrelly questions like these are the essence of Mitchum, a book more aware than most that artistic tastes are a thin veneer laid over primitive urges, and pretending anything different might not be worth the bother. Each fresh encounter with Blutch comics can be disorientating. Along with the density and weight of those spiraling black lines—plus the fragmentation of the storylines, which in Mitchum push past surrealism and into stretches of formal experimentation—there's also the brutality that he depicts, often inflicted upon women. In Total Jazz, the series of vignettes related to jazz and jazz musicians reprinted by Fantagraphics in 2018, Blutch casually dashes off panels of authentically distressing domestic violence, like the one when an angry male sax player abruptly punches his lady so hard that his fist seems to replace her face in space. Mitchum has its own passages of aggro, not least in the hypnogogic pages where Robert Mitchum himself turns up, a chapter to which a reviewer should take a long run-up. But in calmer moments too the erotic charge of the art is constantly trailed by looming shadows of a cost, mental and physical. And yet, Mitchum is exhilarating, stories of love, opportunity, and (frequently) dancing, depicted with enough understanding to leave Blutch revealed as an incurable romantic.

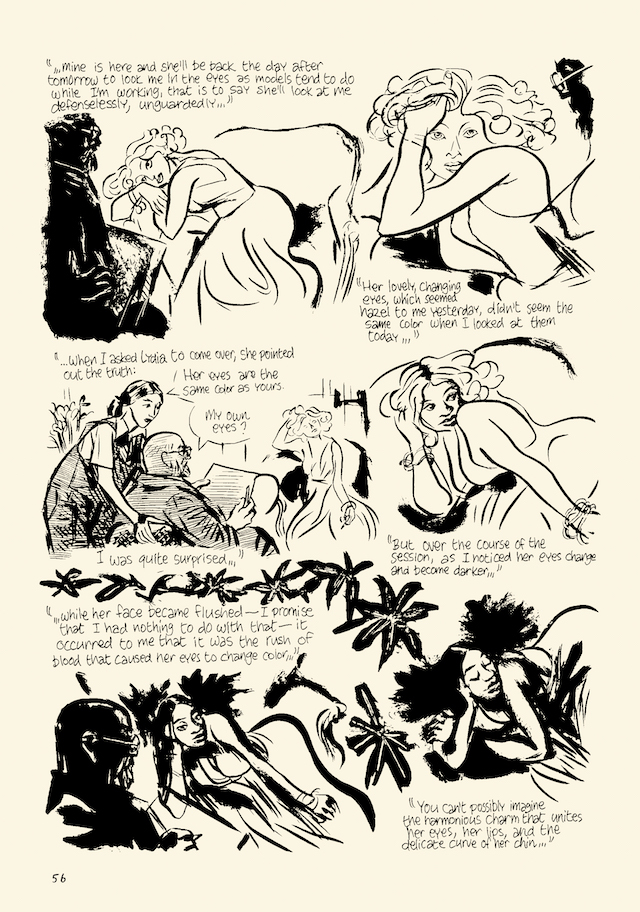

Mitchum collects the five separate Numéros originally put out by Éditions Cornélius in the late 1990s, presented here alongside a section of unfinished and unpublished pages. Improvisation is the wrong term for Blutch's storytelling, which often feels closer to a dérive, but even in the book's most earthly and conventional chapter—a sweet Parisian La Ronde of two couples, a painter, and a passing muse—the figure of Henri Matisse suddenly materializes without warning as a bit player. There are no accidents in Blutch, and if Matisse is a presiding spirit then so too must be Dance, Matisse's famous painting of bodies in motion that perhaps occupies Mitchum's subconscious, a motivation for Blutch's constant attempts to draw dance and capture on paper what happens when humans do that exhilarating thing. That same Numéro 4 contains another metaphysical dance routine, in which another female dancer is stripped by her partners while an artist at an easel pays close attention, although now he's some fairly terrible thing with the mouth of a lamprey. Her expression is wide-eyed and fixed, mouth agape, even as her body twists and folds. She could be read as terrified or intimidated, were it not for her evident commitment to the dance and total control over the sequence, to the point where the other figures disassemble into cubist structures and fly apart under the strain of the activity, leaving just geometric rubble on the floor. That look on her face is the euphoria of physical movement, captured in ink over multiple panels on the static page of a comic.

Mitchum collects the five separate Numéros originally put out by Éditions Cornélius in the late 1990s, presented here alongside a section of unfinished and unpublished pages. Improvisation is the wrong term for Blutch's storytelling, which often feels closer to a dérive, but even in the book's most earthly and conventional chapter—a sweet Parisian La Ronde of two couples, a painter, and a passing muse—the figure of Henri Matisse suddenly materializes without warning as a bit player. There are no accidents in Blutch, and if Matisse is a presiding spirit then so too must be Dance, Matisse's famous painting of bodies in motion that perhaps occupies Mitchum's subconscious, a motivation for Blutch's constant attempts to draw dance and capture on paper what happens when humans do that exhilarating thing. That same Numéro 4 contains another metaphysical dance routine, in which another female dancer is stripped by her partners while an artist at an easel pays close attention, although now he's some fairly terrible thing with the mouth of a lamprey. Her expression is wide-eyed and fixed, mouth agape, even as her body twists and folds. She could be read as terrified or intimidated, were it not for her evident commitment to the dance and total control over the sequence, to the point where the other figures disassemble into cubist structures and fly apart under the strain of the activity, leaving just geometric rubble on the floor. That look on her face is the euphoria of physical movement, captured in ink over multiple panels on the static page of a comic.

Robert Mitchum looms ahead, but first a mention of Blutch's most formal game, a venture into conceptual comics territory, again in Numéro 4. The extras section of the NYRC volume contains pages of an unfinished modern-dress Western tale, in which two women team up to locate a kidnapper and his victim, a story of cruelty and Texas landscapes that suggest Blutch storyboarding a Sam Peckinpah film. But in the published version, each of these pages is overlaid and almost obscured with a single incongruous and non-narrative drawing of a female dancer, caught in performance. Two completely discrete graphic universes overlap, their connection an enigma. If the Texas tale is about violence and vengeance, then a dancer floats above all such mundane traumas, as free as the air—until she eventually becomes that dancer being assaulted by the sailors, condensing out of one abstract state of grace into another that's noticeably worse.

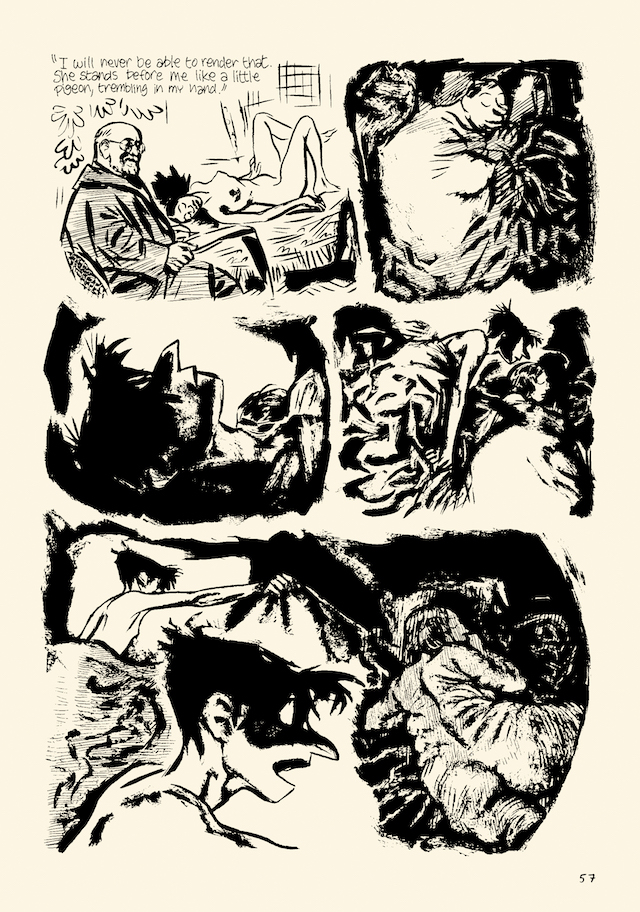

The Mitchum in Mitchum arrives during Numéro 3, a fractured police procedural whose only logic is dream-logic. The story's avatar of Robert Mitchum shape-shifts between different eras of the actor's physical form: an elderly big-spectacles Mitchum of the 1990s voyeuristically watches a sleeping young couple in their apartment, then morphs into Reverend Powell from The Night of the Hunter, and then shifts again into the virile evil Mitchum of Cape Fear. While in this form, he assaults a young woman and gets into a fight with a kick-ass cop visually coded as Pam Grier in her blaxploitation pomp. Two great Blutch pages ensue: an alarming image of Mitchum looming over a terrified woman lying on the ground and standing on her long hair, and then Mitchum swatting Grier away in mid-air like an annoying mosquito, just as she's flying in for a kung fu kick, as violent a collision as any Kirby panel. At the end, Mitchum shrinks back down to his elderly state and becomes another nobody, lost in the crowds on a subway train. Interpretations can wander far and wide, about the shriveled core of misogyny escaping into anonymity, or possibly being trapped inside it. Or about the effects of on-screen violence possessing some passing nobody, a notion Howard Chaykin might chew on, not to mention David Lynch. Mitchum doesn't deal with cinema directly—So Long, Silver Screen is the Blutch book to seek out for that—but here it crowbars the supposedly dream-like ambience of film noir into a truly quixotic mode of comics, and makes the movie version look weighed down by logic and reality. Which also makes Numéro 3 a legitimate piece of film criticism, on top of anything else. There is a movement underway to embrace video essays as a more authentic form of film criticism than that fusty and past-it dinosaur, the written word; Numéro 3 vaults so far past a formal close-reading analysis of cinema that it makes videographers appear to be barking up the wrong tree.

The Mitchum in Mitchum arrives during Numéro 3, a fractured police procedural whose only logic is dream-logic. The story's avatar of Robert Mitchum shape-shifts between different eras of the actor's physical form: an elderly big-spectacles Mitchum of the 1990s voyeuristically watches a sleeping young couple in their apartment, then morphs into Reverend Powell from The Night of the Hunter, and then shifts again into the virile evil Mitchum of Cape Fear. While in this form, he assaults a young woman and gets into a fight with a kick-ass cop visually coded as Pam Grier in her blaxploitation pomp. Two great Blutch pages ensue: an alarming image of Mitchum looming over a terrified woman lying on the ground and standing on her long hair, and then Mitchum swatting Grier away in mid-air like an annoying mosquito, just as she's flying in for a kung fu kick, as violent a collision as any Kirby panel. At the end, Mitchum shrinks back down to his elderly state and becomes another nobody, lost in the crowds on a subway train. Interpretations can wander far and wide, about the shriveled core of misogyny escaping into anonymity, or possibly being trapped inside it. Or about the effects of on-screen violence possessing some passing nobody, a notion Howard Chaykin might chew on, not to mention David Lynch. Mitchum doesn't deal with cinema directly—So Long, Silver Screen is the Blutch book to seek out for that—but here it crowbars the supposedly dream-like ambience of film noir into a truly quixotic mode of comics, and makes the movie version look weighed down by logic and reality. Which also makes Numéro 3 a legitimate piece of film criticism, on top of anything else. There is a movement underway to embrace video essays as a more authentic form of film criticism than that fusty and past-it dinosaur, the written word; Numéro 3 vaults so far past a formal close-reading analysis of cinema that it makes videographers appear to be barking up the wrong tree.

Blutch's figures observe each other, paint each other, desire and hurt each other. What are they all up to? Some of Mitchum is a masochistic view of spectatorship—there's another Chaykin idea—but the best name for all that stuff might be, as noted, obsession. In Mitchum characters teeter on the brink of obsession and sometimes tip right in, but Blutch consistently fails to condemn obsession as irrevocably negative. This is an old artistic principle, the one emerging from romanticism that says obsession can be a dynamic liberating impulse, one with revolutionary potential. And it's a principle currently having a hard time of it, in an era where innate impulses are so mistrusted that the relevant authorities try the hopeless task of policing them. Mitchum, a tough and uncompromising read for sure, is also entirely about embrace and empathy; and in its violence and sexual conflicts, the pleasure principle endures. Not seeing that in there might amount to not looking at the work.

Blutch's figures observe each other, paint each other, desire and hurt each other. What are they all up to? Some of Mitchum is a masochistic view of spectatorship—there's another Chaykin idea—but the best name for all that stuff might be, as noted, obsession. In Mitchum characters teeter on the brink of obsession and sometimes tip right in, but Blutch consistently fails to condemn obsession as irrevocably negative. This is an old artistic principle, the one emerging from romanticism that says obsession can be a dynamic liberating impulse, one with revolutionary potential. And it's a principle currently having a hard time of it, in an era where innate impulses are so mistrusted that the relevant authorities try the hopeless task of policing them. Mitchum, a tough and uncompromising read for sure, is also entirely about embrace and empathy; and in its violence and sexual conflicts, the pleasure principle endures. Not seeing that in there might amount to not looking at the work.