Andy Douglas Day is a great director of his characters gestures and facial expressions. His narratives are essentially two-person comedy bits, and like Rick Altergott's masterful humor comics, the climax of the joke is often in a throwaway detail paced panels before the 'punchline.' A shrug, a glance.

And yet stylistically Day couldn't be farther away from Altergott. In fact, devotees of Altergott's neo-Wally Wood renderings might be offended by the very comparison. You would have to be a philistine to call Day's drawings crude, but I know there will be many philisitines saying exactly that when they encounter this tome.

I am often on the side of outré drawing styles in comics because I think there is a natural desire for artists who have hard-to-parse drawing styles to still want to tell stories. I think vague storytelling can be thrilling, but I also love the narrative crispness of comics such as King Aroo. So it's quite a moment when someone like Day creates a bridge between the two extremes, arranging his expressive style in the service of joke-craft and traditional comic strip character duos.

Day's drawing break standard practice on the character level: His protagonists don't immediately register as themselves from drawing to drawing. An Altergott drawing of Doofus is always Doofus and the standard thinking is that is how comics function correctly: you can aestheticize it, but what matters most is maintaining cartoon-integrity from beginning to end.

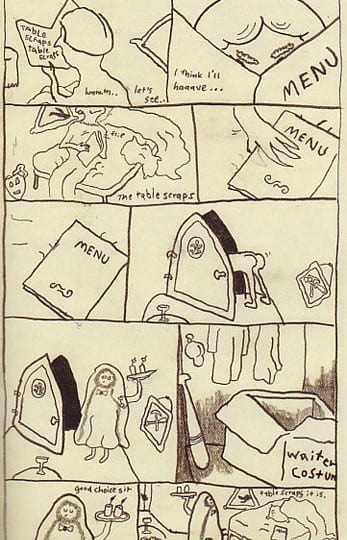

To that rule Day's strips seem to ask so what? The fact that the comedy works so well in spite of all the obstruction should speak volumes to us. Comics is a flexible medium that is too rarely flexed-out, and (more importantly) one that we can take our time with. Day provides us with a simple set-up for the book: Miss Hennipin is a wealthy, eccentric old bat whose man servant, Mokumbo, takes dictation of her letters and helps her through the day. In one scene, we see Mokumbo clock out from work and retire to his small room, where he studies a restaurant menu. After wondering out loud if he should have the table scraps, he scampers off to the closet and dresses up as a waiter, emerging to say, "good choice sir. The table scraps it is."

To that rule Day's strips seem to ask so what? The fact that the comedy works so well in spite of all the obstruction should speak volumes to us. Comics is a flexible medium that is too rarely flexed-out, and (more importantly) one that we can take our time with. Day provides us with a simple set-up for the book: Miss Hennipin is a wealthy, eccentric old bat whose man servant, Mokumbo, takes dictation of her letters and helps her through the day. In one scene, we see Mokumbo clock out from work and retire to his small room, where he studies a restaurant menu. After wondering out loud if he should have the table scraps, he scampers off to the closet and dresses up as a waiter, emerging to say, "good choice sir. The table scraps it is."

Does Mokumbo as a waiter resemble a waiter? Not really. And does he resemble Mokumbo from the previous page? Slimly, perhaps (there are tell-tale Mokumbo signatures, but you must hunt for them). It somehow all comes off because Day's conviction in his own world of image-making/storytelling is so assured. It's not traditional, but definitely affectionate towards comic tropes. If it passes over our heads at first, the strength of what Day is accomplishing is compelling enough for us to put in the proper amount of effort.

And more to the point, Day's drawings are beautiful: he draws Mokumbo in a way that is pleasing/challening to himself from page to page, in the same way a painter would push himself to not rely on stale imagery. Perhaps it's this continued affection for rendering Miss Hennipin and Mokumbo that allows Day to want to continue writing good stories for them?

That's too easy an explanation for what's being carried off here. Over the course of the book (which is basically a collection of different episodes in the duo's lives), Miss Hennipin comes across as odd, hard-edged, friendly, intellectual and funny, i.e. a real character. It's a feat of cartooning prowess that Day's sketchy, always in minor-flux character designs become richer and richer to us as characters the more we read. It's a pleasure to see such wonderful cartooning in a universe of aesthetics and rules in which Day may very well be the sole resident. This book provides richest serving yet of Day's activities in that world.

That's too easy an explanation for what's being carried off here. Over the course of the book (which is basically a collection of different episodes in the duo's lives), Miss Hennipin comes across as odd, hard-edged, friendly, intellectual and funny, i.e. a real character. It's a feat of cartooning prowess that Day's sketchy, always in minor-flux character designs become richer and richer to us as characters the more we read. It's a pleasure to see such wonderful cartooning in a universe of aesthetics and rules in which Day may very well be the sole resident. This book provides richest serving yet of Day's activities in that world.