Sergio Ponchione is an Italian cartoonist who first made his mark with American audiences with his series Grotesque, for the now defunct Ignatz line. That was a collaboration between Fantagraphics and Igort's Coconino Press, and it gave both American and European artists a beautiful showcase for serialized work. Ponchione's debt to a century of American cartooning and animation was obvious in that series, which happened to be about imagination, world-building, and meta-conspiracy theories. One could see the inspiring hands of E.C. Segar, George Herriman, Robert Crumb, and Charles Burns (among many others) influencing his work in a variety of ways. Some European cartoonists are attracted to the myths of America. For example, Moebius was fascinated by the mysticism of Native American culture in the later Blueberry comics. Then there's Belgian cartoonist Morris and his long-running Lucky Luke. More recently, Christophe Blain's Gus and His Gang pays tribute both to the Western and the tropes created by its comics adaptation.

Ponchione, on the other hand, is attracted to the myths (and realities) of the American comic-book creator. Memorabilia is an expansion of a comic book he did for Fantagraphics a few years ago, where Ponchione plays the role of mysterious and vaguely discomfiting mentor, much like his own Mr. O'Blique character. The comic opens with Ponchione welcoming a young cartoonist into his home, one who has had some strange dreams. That leads to the meat of the matter: Ponchione's tributes to his cartooning heroes. He begins with Steve Ditko, in a story called "The Mysterious Steve". In the wake of sometimes weird, intrusive attempts to contact the reclusive Ditko before his death and the focus on his reclusive nature after he died, Ponchione's tribute is simple and respectful. Imitating Ditko's shadowy, distorted style, he indulges in drawing some of Ditko's best-known characters when he imagines what it's like behind his apartment door. But he leaves the story with the simple, basic truth: he was a solitary man who expressed all he had to say to the world through his stories, every day.

The tribute to Kirby is sillier: imagining Kirby teleported away from his grave at the moment of his death to create an alien amusement park. Ponchione's tribute to Kirby's art is inspired, but aping that style is such a familiar trope these days that it doesn't have quite the impact of the rest of the book. It does speak to the way that Kirby's imagination was almost too big to really wrap one's head around, sometimes to the point of incoherence on the part of the artist trying to imitate it.

On the other hand, his tribute to Wally Wood was the best piece in the book. It's illustrated text rather than a panel, and it goes deep into Wood's demons as well as his inspirations. It's a tribute to Ponchione's skill as an illustrator that he was able to recreate an approximation of Wood's work in his own style, revealing just how much the master influenced the bedrock of his line. Ponchione used a gold coin glimmering in the dark as a metaphor for Wood's life as an artist, and he returned to it throughout this biography, appreciation and explication of Wood's technique.

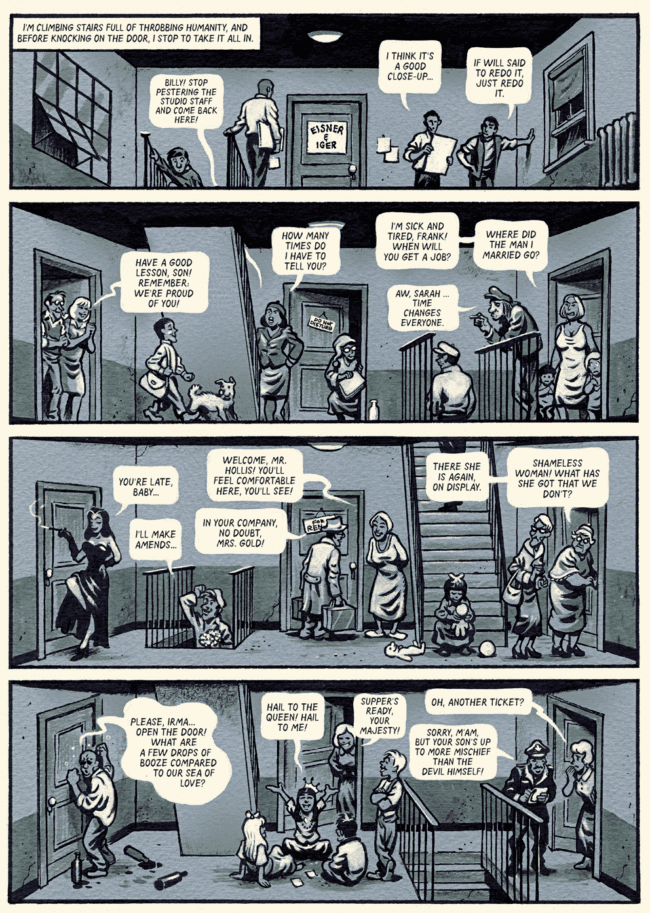

Ponchione added to the initial project by adding on a couple of new connective devices to write about Will Eisner and Richard Corben. The Eisner piece was inspired by an intercom, which sparked a story where a building's intercom nameplate was filled with Eisner's characters, mostly from his Spirit days. The building itself is a take-off on Eisner's clever building/title designs, where buildings would often become part of the title itself. Unfortunately, Ponchione buys into the myth of Eisner as benevolent overlord of his shop, rather than calling it what it was: a cartoonist sweatshop. For someone who championed the vision of the creator, Eisner always swept the fact that he was management under the rug. In this story, he's an office cheerleader. Much better is his stand-in character going up the stairs and encounter a bunch of Eisner-type characters. Again, Ponchione doesn't linger on the idea any longer than it actually merits, but it was disappointing that after such a nuanced meditation on Wood, his take on Eisner was relatively glib.

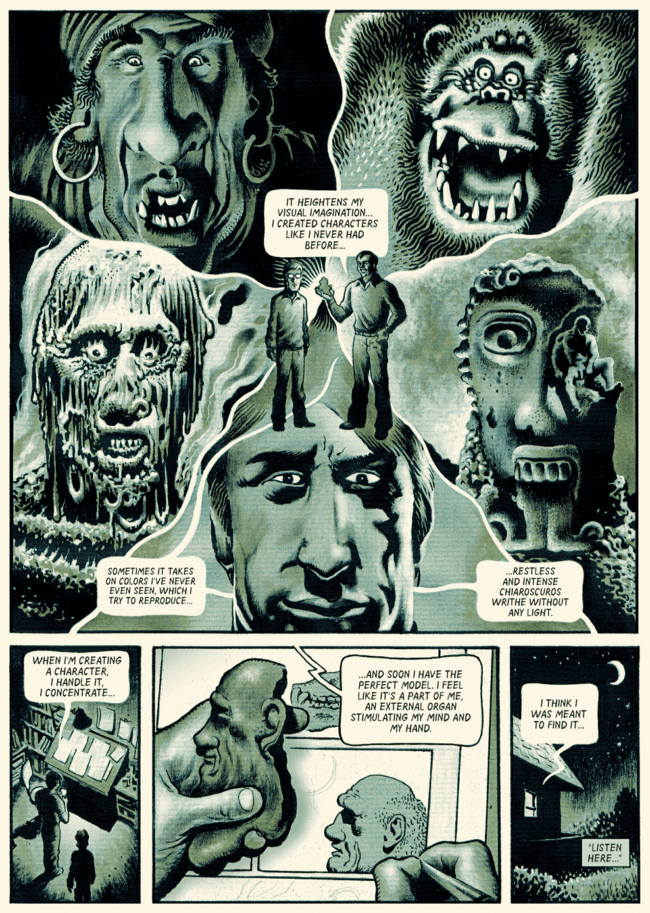

Richard Corben is a fascinating final choice. While the artists from Heavy Metal are beginning to get a reexamination these days, Corben is not someone who's necessarily widely discussed, at least not until he won the Grand Prix at the Angoulême festival last year. In writing about Corben, Ponchione imagines him as a child encountering an alien artifact that gives him special advantages, a scenario straight out of one of Corben's own stories. Ponchione emphasizes the wild visual power of Corben's work, especially with regard to his rubbery, grotesque line and use of shadows.

More than anything, Ponchione writes that reading comics and thinking about his heroes transports him back to that special moment of picking a comic up at a newsstand and getting that rush of being exposed to the imagination of an artist. The essence of his work is the connection between everyday living and the realm of imagination. His obsession is that itch in the back of one's brain, that sense of déjà vu where something seemingly ordinary triggers a memory of a dream. It's his method for writing fiction, and it is also his method for leaning into each of the artists in the book. He hits on an image for each story from everyday life and reverse-engineers it into a hook for each story, giving the biographical elements a unique angle. The final product feels a little thin. Given the brevity of each story, it should have been twice as long. It's certainly worthy of a sequel.