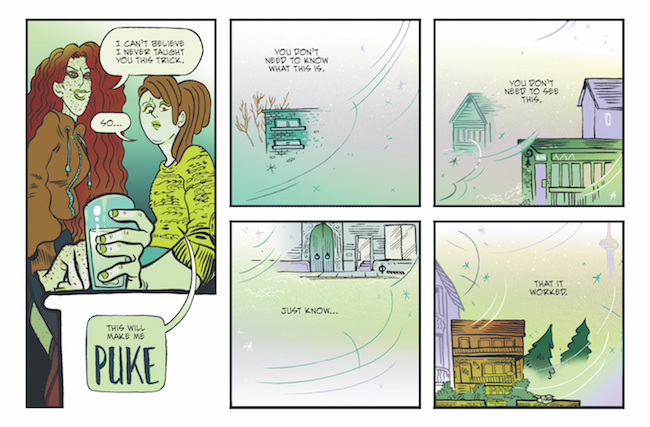

The first thing that strikes me about Meat and Bone is Kat Verhoeven’s incredible skill at drawing memorable characters. Her figures have that warm, animation-ready look that conveys at once movement and emotion, the feelings of an instant and the personality carved by a lifetime of experience made immediately accessible by gesture and shape. But there is something sharper and more angular to her line, at odds with the uniform softness favored in current animation and webcomics styles while not actually rejecting it. There’s a distinctive balance to Verhoeven’s illustrations that gives uniquely defined personality not only to her comics but to each and every one of her characters.

That visual definition is matched by an authorial clarity that is essential to Meat and Bone, a comic about love and eating disorders. The story centers around a group of young women, longtime friends in their twenties who move into an apartment together to get a new start on life. The comic follows each character with equal focus - it’s ultimately a collective story - but the point of view and the main driver of the plot is Anne, a cafe barista recently out of a long term relationship struggling with a negative body image and a past eating disorder. Anne becomes fascinated with and attracted to her neighbor Marshall, a severe and seriously skinny woman obsessed with tarot and living by a philosophy of her own creation. As Anne is drawn into Marshall’s world she is also drawn into Marshall’s eating disorders, stacks of pills and extreme fasting dominating the content of the genuine bond that brought them together to begin with.

Anne’s attraction to Marshall is driven by conflicting desires, an urge to save her and a satisfaction that comes with hearing the worst things you suspect about yourself confirmed to be true by another. But there is also real spark and magnetism to Marshall, a creativity that is genuine and not purely self-destructive at its core. Anne and Marshall are both broken people struggling with a unique pain that they share, and their struggle is one of learning not to inflict that pain in the other while learning to accept that the burden may not need to be carried alone.

Anne’s attraction to Marshall is driven by conflicting desires, an urge to save her and a satisfaction that comes with hearing the worst things you suspect about yourself confirmed to be true by another. But there is also real spark and magnetism to Marshall, a creativity that is genuine and not purely self-destructive at its core. Anne and Marshall are both broken people struggling with a unique pain that they share, and their struggle is one of learning not to inflict that pain in the other while learning to accept that the burden may not need to be carried alone.

Verhoeven jokingly described Meat and Bone in a recent interview at this very site as “like the TV show Friends but sadder,” an apt description for a series that centers around a group of young people figuring out who they are on their own time, whose life experiences converge narratively and physically in the communal space of a shared apartment. However, where Friends’ writing often dresses snide cruelty in the guise of social warmth, Verhoeven’s comic has a great deal of genuine affection for its characters, and gives nuanced attention to their affection for each other. No one’s failings are mocked, nor is pain valorized.

Ultimately this warmth and compassion is balanced by a clear and nuanced understanding of what makes a relationship toxic or abusive. A clear line, difficult draw without becoming didactic, is established over the course of the book between people who are flawed and people who are dangerous, messy relationships worth maintaining and seemingly easy affairs worth ending. Verhoeven takes care not to depict any of her characters as flawless, and captures with admirable realism the confusion of realizing that someone you love may not be good for you. Many of the stories in Meat and Bone converge on questions like these: “Is it time to cut this person out of my life? Am I unsafe? Am I unhappy? What does it mean if I do decide to stay? How will I live on after I make this choice?” Verhoeven’s patience and confidence in depicting these interpersonal and ethical questions, always so much easier to judge from a distance than to experience directly, is no small feat.

Ultimately this warmth and compassion is balanced by a clear and nuanced understanding of what makes a relationship toxic or abusive. A clear line, difficult draw without becoming didactic, is established over the course of the book between people who are flawed and people who are dangerous, messy relationships worth maintaining and seemingly easy affairs worth ending. Verhoeven takes care not to depict any of her characters as flawless, and captures with admirable realism the confusion of realizing that someone you love may not be good for you. Many of the stories in Meat and Bone converge on questions like these: “Is it time to cut this person out of my life? Am I unsafe? Am I unhappy? What does it mean if I do decide to stay? How will I live on after I make this choice?” Verhoeven’s patience and confidence in depicting these interpersonal and ethical questions, always so much easier to judge from a distance than to experience directly, is no small feat.

For readers who call Toronto their home, there will be a lot about Meat and Bone’s depiction of the city that is immediately evocative, from major locations to subtle details. Many of the book’s settings carry some nostalgic intensity just out of circumstance - the old Bloor and Bathurst on page one! RIP Mirvish Village. But what really makes Meat and Bone a special addition to the growing list of great new Toronto comics is the way Verhoeven depicts condo life in the city. There’s an image on page 10 I’ve thought about a lot when I think about this comic, of Anne sitting against a wall in their spacious, as of yet empty new apartment, boxes and still-packed things scattered in front of her. How brightly lit that space is! How far away the door is! How sparse everything seems, even with all your stuff and clutter arrayed out before you! Almost as a counterpart to Deforge’s recently collected webcomic Leaving Richard Valley, which mythologized in its own tender way the places and communities disrupted by rapid high-rise development, Verhoeven captures the feeling of moving into one of those sparkling faceless apartment complexes. Everything around you is new, huge, vacant and impersonal. There’s room enough to call these places your own, make a home for yourself, but it could just as well spit you out, clear you away from memory and occupancy. It’s a setting that Verhoeven characterizes well and is fitting for what her story is ultimately about, people trying to find a definition for themselves in a world too large to feel like anyone else is paying attention.

For readers who call Toronto their home, there will be a lot about Meat and Bone’s depiction of the city that is immediately evocative, from major locations to subtle details. Many of the book’s settings carry some nostalgic intensity just out of circumstance - the old Bloor and Bathurst on page one! RIP Mirvish Village. But what really makes Meat and Bone a special addition to the growing list of great new Toronto comics is the way Verhoeven depicts condo life in the city. There’s an image on page 10 I’ve thought about a lot when I think about this comic, of Anne sitting against a wall in their spacious, as of yet empty new apartment, boxes and still-packed things scattered in front of her. How brightly lit that space is! How far away the door is! How sparse everything seems, even with all your stuff and clutter arrayed out before you! Almost as a counterpart to Deforge’s recently collected webcomic Leaving Richard Valley, which mythologized in its own tender way the places and communities disrupted by rapid high-rise development, Verhoeven captures the feeling of moving into one of those sparkling faceless apartment complexes. Everything around you is new, huge, vacant and impersonal. There’s room enough to call these places your own, make a home for yourself, but it could just as well spit you out, clear you away from memory and occupancy. It’s a setting that Verhoeven characterizes well and is fitting for what her story is ultimately about, people trying to find a definition for themselves in a world too large to feel like anyone else is paying attention.