There was a time when no country appreciated its comic artists and creators less than Britain, which would represent victory in a crowded field.

This opinion could easily have appeared in the text pages of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's energetic two-decade binge on the intoxicating crank of imaginary fictions, which concluded last year with a hangover. Switchbacking between the styles of several British comics on the way to a final full-stop mimicking 2000 AD, LOEG Volume IV: The Tempest took the opportunity to include eulogies for a set of storied British comics artists and writers from multiple eras, itemizing the disrespect and ruination that came alongside work in the domestic industry's salt mines. Having started out with a readers' awe for the creations, LOEG finished up pondering the indignities inflicted upon the creators, its writer feeling by then that he had endured a few too many himself.

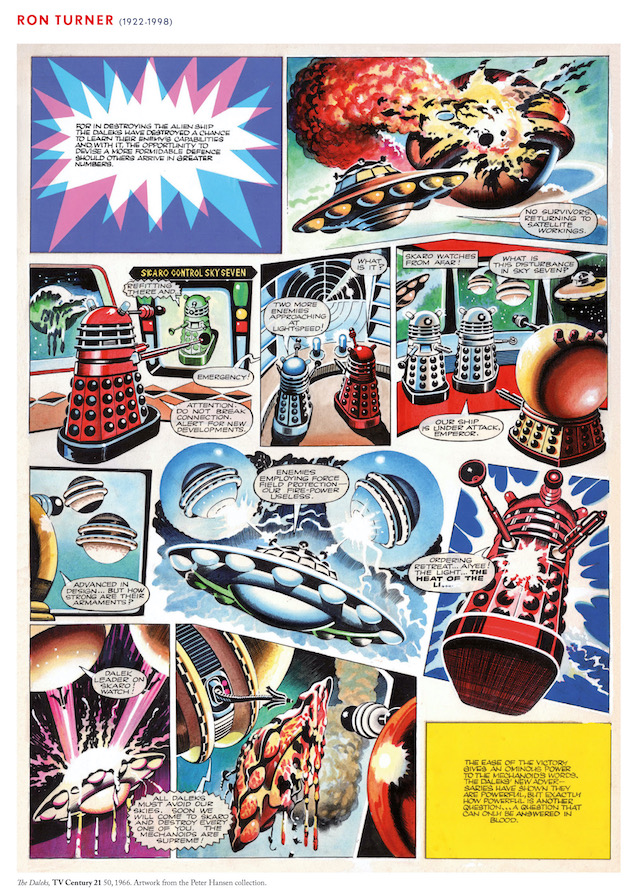

In fact, that opening sentiment comes from David Roach, who carefully phrased it in the past tense while discussing his book Masters of British Comic Art. This hefty coffee-table tome, published by Rebellion, aims to give due appreciation to several of those British creators and many more besides, while corralling the UK's sprawling and eccentric comics history into one coherent chronology. But here too, Roach's text finds space to allude to some unhappy details. About Paddy Brennan, a fixture in humor strips and girls' comics in the 1950s and 1960s, never allowed to sign his name while read by thousands of people, and who died at his drawing board a week before being discovered. About Ron Embleton and Jim Holdaway, colossal talents dead at 57 and 42. About Frank Bellamy, one of LOEG's highlighted cold cases and a legendary Eagle stylist, plenty of whose art was stolen or destroyed.

"This book doesn't dwell on the negative; but it is a cruel industry," Roach told me. "In the mid-2000s I sorted out the old comics art then held in the IPC warehouse, where only work felt to have resale value or worth as capital had survived. It was seen as a commodity, and the art believed to be of no value was burnt. That is the story of British comics until the 1970s, when people like Pat Mills and John Wagner came in, who felt that artists' work was not disposable."

David Roach can tell some of that story from his position as an artist in 2000 AD and elsewhere, but the book is more directly a product of his work as collector and curator. In 2016 he wrote Masters of Spanish Comic Book Art for the publisher Dynamite—something of a dream project, given the influence of Spanish artists on Roach's own art style—and the new book follows a similar structure. Illustrated text chapters outlining the history of the British industry are followed by a lengthy artists gallery presenting individual pages, often from the original boards. But the switch in topic has brought a change of scale, with the new book clocking in at 340 (unfortunately unindexed) pages compared to the earlier book's 270.

David Roach can tell some of that story from his position as an artist in 2000 AD and elsewhere, but the book is more directly a product of his work as collector and curator. In 2016 he wrote Masters of Spanish Comic Book Art for the publisher Dynamite—something of a dream project, given the influence of Spanish artists on Roach's own art style—and the new book follows a similar structure. Illustrated text chapters outlining the history of the British industry are followed by a lengthy artists gallery presenting individual pages, often from the original boards. But the switch in topic has brought a change of scale, with the new book clocking in at 340 (unfortunately unindexed) pages compared to the earlier book's 270.

An expansion was inevitable, since the book attempts to get its arms around the entire sprawling British comics tradition rather than any one tributary: not just the adventure comics, but also newspaper strips, comics for girls, nursery comics, plus the anarchy of the humor titles whose roots lie deep in the nation's ribald cultural soil, and then pull all the threads into the present day.

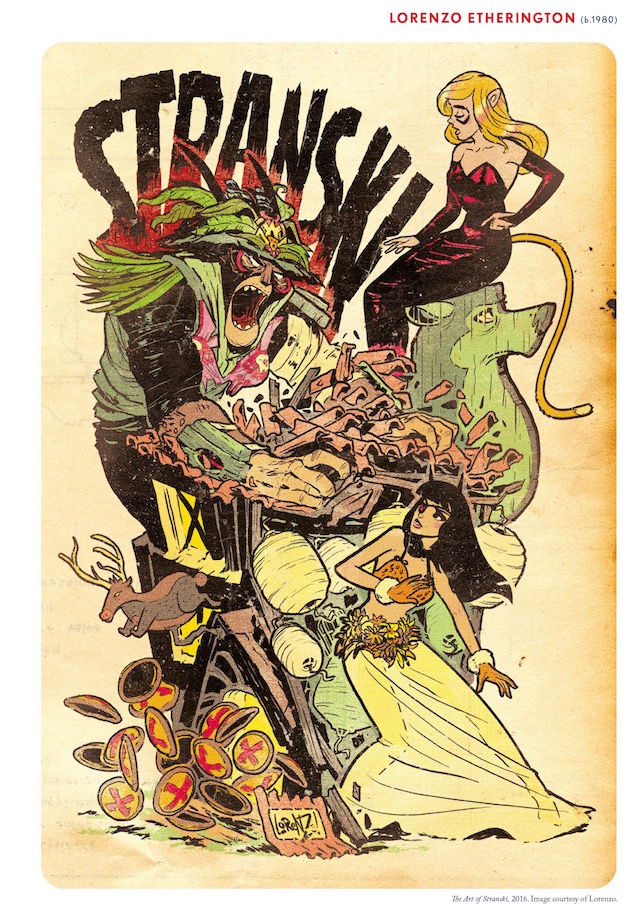

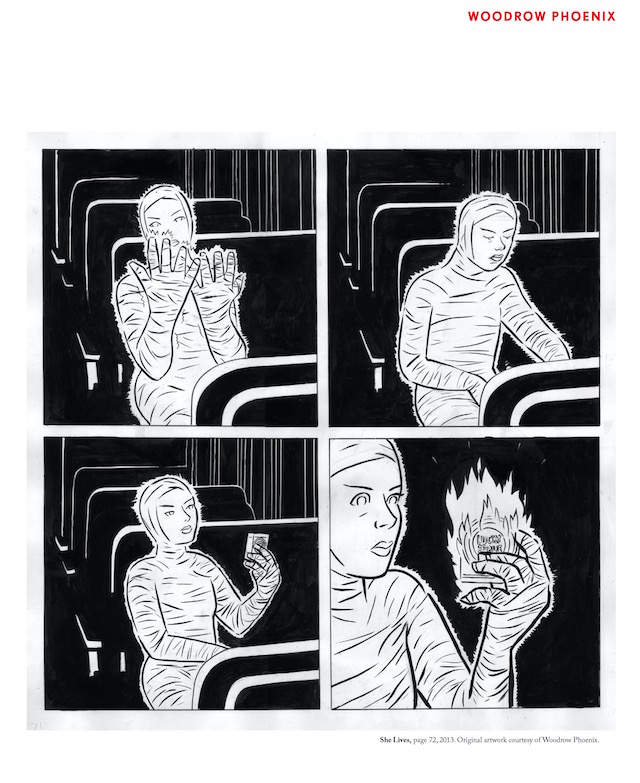

"If you are going to do book on this subject then you have to bring in the genres and strands that are sometimes ignored, since each has had its own geniuses," says Roach. "Including the world of nursery comics lets me show a 1961 page by Gordon Hutchings from Gulliver Guinea-Pig, beautifully drawn on huge pages and deeply eccentric while made for the under-fives. At the other end of the chronology I needed to recognize current individualists like Woodrow Phoenix, creator of the seventy-two page, one-metre square wordless strip called She Lives about the life of the Bride of Frankenstein. Just one copy of this comic exists, and to read it you need Phoenix to arrange a display himself. Only a substantial book could tie these different figures into the one story."

On top of genre diversity, the periods of artistic interbreeding with other nationalities makes defining a unified British comics style harder still. Roach's chronology describes the period in the 1950s and 1960s when Italian and Spanish artists supplied a wealth of comics pages to the then-ravenous British industry through agencies. The author's British and Spanish books navigate around each other in these particular sea lanes. They both emphasize the 1957 trip to London by Josép Toutain of the agency Selecciones Ilustradas with a portfolio of Spanish artists in his briefcase as a moment with drastic consequences for the comics industry in both countries, years before Toutain managed to have his other legendarily impactful run-in with Jim Warren in the US.

On top of genre diversity, the periods of artistic interbreeding with other nationalities makes defining a unified British comics style harder still. Roach's chronology describes the period in the 1950s and 1960s when Italian and Spanish artists supplied a wealth of comics pages to the then-ravenous British industry through agencies. The author's British and Spanish books navigate around each other in these particular sea lanes. They both emphasize the 1957 trip to London by Josép Toutain of the agency Selecciones Ilustradas with a portfolio of Spanish artists in his briefcase as a moment with drastic consequences for the comics industry in both countries, years before Toutain managed to have his other legendarily impactful run-in with Jim Warren in the US.

Roach notes that by the late 1950s UK comics employed the absolute greatest world comics artists. "Not just our own stars, but Alberto Breccia, Hugo Pratt, Dino Battaglia, Gino D'Antonio… The British market was simply that large, an enormous, voracious industry, which needed more comics art than the locals could possibly supply. From then onwards, any talk of a 'British' style has to be a shorthand for various elements mixed from different places, so a book on the subject has to reflect that too."

Any book on the subject written since 1977 also has to assess the role that 2000 AD itself has played on the British comics stage, as a venue for British creators to become recognized and a talent pool for the US industry to access. The Masters book arrives from 2000 AD publishers Rebellion following that company's recent acquisition of a substantial swathe of British comics history, through its purchase of the archives of publishers IPC. Roach proposed the book before those business deals were public knowledge, but Rebellion surely saw the chance to publish a substantial work of curation on the subject of British comics in the context of its spending on the same heritage.

Kevin O'Neill famously did that heritage a favor when he introduced creator credits to the pages of 2000 AD without asking and, as Pat Mills once put it, changed the industry forever. Before that, the wish of publishers to keep creators unidentified guaranteed that the names could go missing. Rebellion's Treasury of British Comics project has been reprinting work from its IPC archives, but even it has been forced to leave some of the artists unnamed, presumably now to stay anonymous permanently.

Kevin O'Neill famously did that heritage a favor when he introduced creator credits to the pages of 2000 AD without asking and, as Pat Mills once put it, changed the industry forever. Before that, the wish of publishers to keep creators unidentified guaranteed that the names could go missing. Rebellion's Treasury of British Comics project has been reprinting work from its IPC archives, but even it has been forced to leave some of the artists unnamed, presumably now to stay anonymous permanently.

Roach's book distils these historical question marks into one page in its artists gallery, a piece of original art by a creator labelled Unknown. It comes from Princess comic, 8th September 1962, a story called "Heiress to Tangurau" drawn in shades of grey wash that represent the New Zealand dusk and also happen to delicately emphasize the orphaned white girl featured in the story. The strip has previously been attributed to Leslie Otway; but Roach disagrees, seeing a different technique, and indeed a different agency, than Otway's at work.

"This artist stands in for the others who were ignored then or forgotten now. I feel affronted by their unacknowledged labor, and by the publishers who insisted upon it being so. This page is by someone working with the Rogers agency, who seems to have been active in girls' comics for a period of years, and their name and life story is lost. This book is partly to recognize these artists who never went to conventions and had no recognition. You haven't heard of them, but here they are."

"This artist stands in for the others who were ignored then or forgotten now. I feel affronted by their unacknowledged labor, and by the publishers who insisted upon it being so. This page is by someone working with the Rogers agency, who seems to have been active in girls' comics for a period of years, and their name and life story is lost. This book is partly to recognize these artists who never went to conventions and had no recognition. You haven't heard of them, but here they are."