Marx: An Illustrated Biography is a remarkable work, with a comics backstory that the two talented collaborators themselves are not likely to have encountered.

We are evidently in a literary era bursting with biographies—perhaps history minus progress has now returned large thoughts to individual lives—and today’s comic artists do not wish to be absent. Philosopher Bertrand Russell (Logicomix) and Congressman John Lewis (March) seem have garnered the most interest (and sales) so far, but older readers will surely recall another, related tradition or set of traditions.

Rius (Eduardo del Rio), at eighty possibly the most prolific leftwing comic artist on earth, brought out Marx for Beginners in translation in 1972, a bestseller launching the “New Beginners” series of books designed mainly but not only for youngsters. This artistic-political-sales phenomenon is an especially important point for comics history. Famed 1940s artist Will Eisner, coming out of retirement with A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories in 1978, is often credited with the first English-language graphic novel, and Art Spiegelman created Maus, the singular graphic novel that brought a Pulitzer to its artist and a version of the art itself to MOMA: together, they arguably made a genre possible. Hold on, though: Marx for Beginners actually appeared earlier, and may very well have had as much impact as either of these had on an evolving, global art form.

But was it a comic? Rius’ art, clear and crisp prose, illustrated by splashy graphics, mostly lacked the essential, sequential-panels format. It reached millions, through dozens of translations, and yet bears an uncertain resemblance to the revolution in comic art kicked off by rebellious 1960s generations and the post-1990 revolutions of Maus, Harvey Pekar’s assorted works, Alison Bechdel's Fun Home, and others to follow. Rius’ share, looking back, was evidently a part of a different tradition or mixed traditions.

But was it a comic? Rius’ art, clear and crisp prose, illustrated by splashy graphics, mostly lacked the essential, sequential-panels format. It reached millions, through dozens of translations, and yet bears an uncertain resemblance to the revolution in comic art kicked off by rebellious 1960s generations and the post-1990 revolutions of Maus, Harvey Pekar’s assorted works, Alison Bechdel's Fun Home, and others to follow. Rius’ share, looking back, was evidently a part of a different tradition or mixed traditions.

Generations ago, famed Masses magazine artist Hugo Gellert produced the woodcut book, Karl Marx’s Capital in Lithographs (1934), which might possibly be seen as the granddaddy of Everything Marx later—just as the woodcut “comic” created by Gellert’s contemporaries (Lynd Ward, et.al.) saw a rapid rise and fall in the US. Since the 1990s, Trotsky, Che (several versions by different artists), Emma Goldman, and a large handful of other classic political revolutionaries have been rendered in today’s comic biography style. Assorted works of popular explanations-with-illustrations have also been made around Marx’s writings. One extremely strange, actual comic-format work, Marx-Engels, The Communist Manifesto Illustrated (from the little Canadian firm of Red Quill) is an extended visual metaphor of modern misery including the misery of Russians under Stalinism, with Marx the persona absent.

None since Rius’ approach, however, have approached the comic form of “life and work” for Marx himself. The subject has been waiting, but no more. On the other hand, this Marx is definitely sui generis in new and different ways, most especially within the comics world itself. Marx: An Illustrated Biography might even be subtitled “Karl Marx For Kids.”

Asked by this reviewer about influences and styles, the collaborators were a bit Delphic. “There was no plan, it just came spontaneously.” But also “Fred [Grivaud], author of Philémon. As far as the drawing is concerned… [Claire] Bretécher, Julie Doucet, to [Marcel] Gotlib.” In other words, pretty much modern French art comics at large. I guess this works, if never entirely losing the schematized result of seeking to capture large and complex issues through a nimble narrative and clever art.

Nobrow happens to be a British publisher, more successful lately with its imprint Flying Eye offering mostly books for youngsters not quite at the “YA” age. Many of their books appear physically large, giving the artist (and writer) the kind of room more normal for young people’s eyes and sensibilities. Marx also has the brilliant use of color that illustrators of young people’s genres count upon and badly need. Maier and London earlier did a Freud bio in similar format.

Ah, but how well can the Marx saga be covered, interpreted, and understood in sixty pages, however large and colorful they may be? This is a crucial question, but perhaps not the only crucial question. There is so much to Marx (think only for Volumes 2 and 3 of Capital!) that no book, comic or otherwise, can hope to capture all of it, and many have failed in the effort. The question facing comic artist/writer is, or I should say seems to me, how will the reader who knows little, and much of that wrong, come away with a useful framework for grasping what Marx was about and why Marx remains important after all this time.

Today’s prose biographies seem to be less scholarly than “writerly,” and that may be a pointer in the direction of Marx: An Illustrated Biography. The bibliography at the end of the comic offers no secondary works, which is surely a curious thing if not necessarily a lapse of acknowledgments. But it can’t be said that the collaborators, Maier and Simon, have made any serious stumbles. The life is told with verve and more than a dash of humor, which may owe more than a little to the backstory of Corrine Maier, a psychoanalyst, writer of a French bestseller mocking corporate culture, and to the nature of her collaboration with artist Anne Simon on an earlier Freud biography that looks and feels pretty similar to this one.

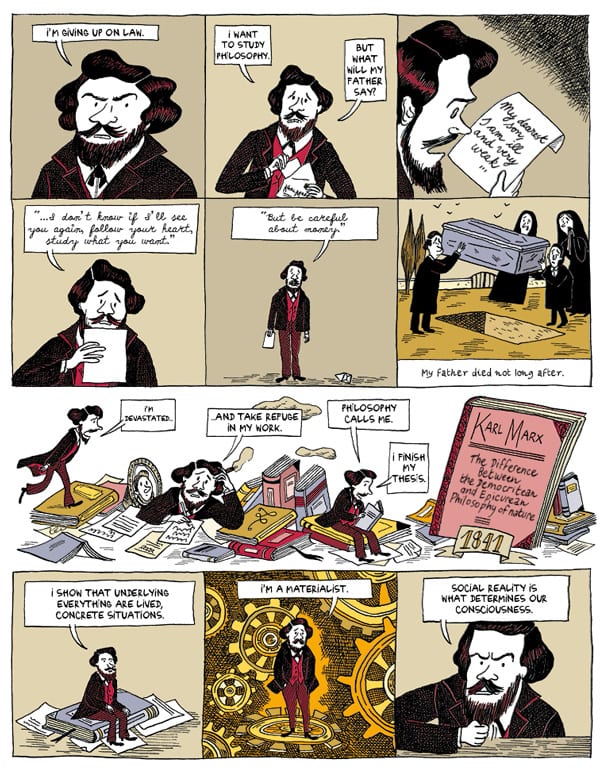

So, Marx. The cerebral young Jew (converted by his father to Christianity), romantic swain wooing the Catholic girl Jenny, rebellious intellectual at the start of a long subversive career, leads well into his life as a wandering visionary revolutionist.

Perhaps because the artist-author combination is reaching for caricature while working heavily on the storytelling, we learn far more about Marx the person than his political and theoretical life’s work. Not that the latter is absent. Some basics of exploitation and profits, for instance, should be convincing to sympathetic readers. Marx’s efforts to create a political mechanism for cross-border solidarity in the International Workingmen's Association (aka First International) look, sympathetically, like the herding of hissing cats—not far from the ideological realities. But the collaborators’ hearts are not really here. As the pair told me, through the publisher: “None of us wanted to do something realistic and boring… We wanted something fresh and creative… There was no plan, it just came spontaneously.”

So: again, it is the life, the trials of the Marx family (not excluding the pregnancy of the maid, while Jenny is off with her mother), the grinding poverty, the devoted daughters, the personal illness and disappointments, that come across in pages otherwise more playful than didactic. That may be not only in line with what should be expected of a biography today, but especially in line with the latest of a popular works on the subject himself, Jonathan Sperber’s well-received Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life (2013).

The last ten pages, rather too condensed for this reviewer’s taste, carry us from the revolutionary’s envisioned socialism (seen cleverly here as hippies smoking dope and having a grand old time) to the mental cogitations of finishing Capital (at least the first volume), personal illness, old age, death, and magical reappearance in the present, wearing a superhero cape and tights. This flying Marx is alive and kicking.

The recapture of a nineteenth century life for a twenty-first century audience of readers under the age of thirty, for whom labor and socialist movements are (almost) a thing of the past, could be no easy task. Even less a task likely to please grouchy middle aged Marxist intellectuals looking for faults and limitations. But young readers are destined to enjoy this book immensely.

Paul Buhle, author of Marxism in the US, interviewed the erstwhile Masses magazine artist Hugo Gellert in his 93rd year, and has collaborated on two “For Beginners” comic art volumes.