A lot of "graphic novels" coming out from major publishers these days really seem to be variations on the graphic memoir. A cynic might say that many of them derive their hook from being about death, illness, abuse, tragedy, etc. An alarming number of them have come from first-time long-form cartoonists and are aimed squarely at the sort of mainstream reader who enjoys this sort of confessional, miserabilist but ultimately triumphant story about tragedy and unfortunate circumstances. I'll rattle off a few titles in this vein: Cancer Vixen, Stitches, The Impostor's Daughter (perhaps the most egregiously manipulative example of this sub-genre). As someone who has long found autobiographical comics to be rewarding on any number of levels, some of these books feel like a distressingly cynical way to make money on the part of the publishers. Life and death is big business, after all.

That's why it was so refreshing to read Ellen Forney's Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, & Me. It's less a story than it is a therapy journal comic, but Forney's instincts as an entertainer kick in even on the dreariest of pages. It's about her experience being treated for bipolar disorder (aka manic depression). Forney has plenty of alt-comics bona fides, from her delightful Tomato comic in the '90s, her hilarious childhood memoir Monkey Food, the amusing short story collection I Love Led Zeppelin, to Lust, her collection of clever illustrations for The Stranger. She's a comics lifer, even if much of her recent output has been as an illustrator. This is by far the longest story she's ever done, and while the book wobbles at times, the sheer attractiveness of Forney's line and her willingness to pour her heart out on the page gives it momentum.

What also sets the book apart from similar fare is Forney's exploration of how mental illness's possible connection to creativity. When diagnosed, she almost glibly notes that she's joined the "Club Van Gogh" of bipolar artists and writers. And as the first couple of chapters of the book illustrate, cycling through the manic phase of her illness initially gives her a constant feeling of exhilaration. Every idea is brilliant. Every person met is a chance for a memorable sexual encounter or opportunity for a magical adventure. Everything is a million miles an hour, and she sweeps up everybody into her wake, while every choice she makes has the potential to start a personal, artistic or political revolution. Of course, the down side of mania is that it potentially leads to poor decision-making, narcissistic behavior, and a general inability to really focus.

Of course, in the moment, as Forney relates, it's akin to being on long-lasting crystal meth. Only the crash that follows lasts for weeks or months, and it gets worse as one gets older. With the story told in retrospect, Forney does pile on her slightly younger self and plays up her more foolishly stubborn decisions regarding her lifestyle and health. For example, Forney opts to eschew medication at first, "working" during her up cycle on some crazy tangential projects. Forney spends a lot of time in the early goings of this book on her sillier exploits. I'm not sure if this is because she wanted to balance the darker portions of the book with lighter fare, or if she found anecdotes like doing a pornographic photo reference shoot (for Eros Comics, natch) where she and two friends pretended to be a "grrl band" in a dressing room amusing in their own right. As a reader, it felt like a little of both; Forney may not quite be an exhibitionist, but she's certainly an oversharer. She's someone who's always had crazy stories to tell even while growing up, and to a degree her own life was influenced by those experiences, such that she went out of her way to do crazy things both for the moment itself but more importantly for a chance to tell someone about them later.

That urge is what makes Forney such a charming storyteller. The problem that she faces in the book is that while she recognizes that she was unbalanced, she views that as the source of her creativity. Some of the anecdotal research she does indicates that some artists indeed linked their agony to their creativity, like Edvard Munch. Like many, she also worries that medication would change her personality, a stance she clings to until she enters the worst depressive phase of her life. Then, and only then, is she ready to listen to her psychiatrist regarding medication, a tenuous process that takes years to properly figure out. It is also one that she subtly sabotages, as she withholds from her therapist her continued pot smoking and refuses to consider doing things like yoga. Again, she stacks the deck narratively against her younger self, but it eventually becomes clear why she must do so.

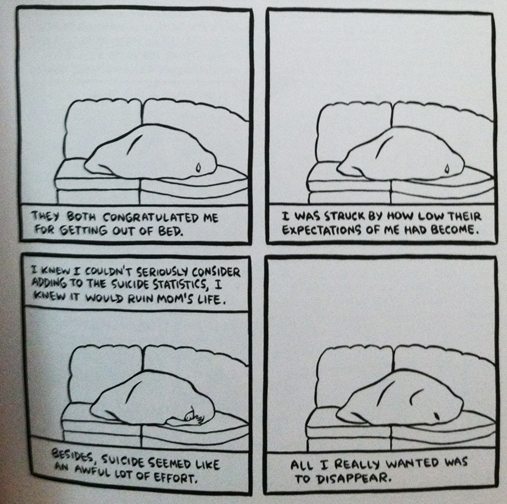

Forney switches back and forth between a simplistic, almost stick-figure style; her familiar smooth and cartoony style; and the occasional highly naturalistic drawing designed to jolt the reader. If the first third of the book is a roller coaster going straight up, then the next third is that same ride plunging downward for an impossibly long time. Here, Forney shares her actual journal sketches from that time, drawn as she attempted to capture the precise feelings of depression, anxiety, and despair. She opens the fourth chapter in a minimalist style as she uses fourteen borderless panels to document her journey from her bed to her couch. During her deepest depression, this is about as far as she could make it some days. This is a journey that actually moves both her mother and therapist to congratulate her, a compliment that tastes bitter in Forney's mouth. Forney's sketchbook drawings are remarkable, capturing the ugly, distorted feeling of depression with an almost visceral level of rendering.

Most of the rest of the book can be described as Forney desperately trying to get off that rollercoaster and lay down her own, more level track. There's a sense of her desperately trying to make connections, even as she isolates herself as a result of the depression (a very common phenomenon). Even if she feels unworthy of the attention of her friends and loved ones, she still seeks "company" in writings about depression. The simple act of finding a way to feel less alone is the foundation for her recovery. Her sessions with her therapist are for a while her only moments of relief, offering a space to ward off the immobilizing grip of depression. Certain techniques more commonly used for other disorders (like a bunch of tricks from cognitive behavioral therapy) are also part of the story.

However, the balance of the book concerns the tricky, uncertain, and ever-evolving relationship Forney has with her medication. Toward the end, there's a stunning section where she goes into detail regarding each of the medications she takes, their positive effects, and their side effects. Lithium, the oldest of all medications for bipolar disorder, can cause severe rashes and memory loss. Other medications affect her blood counts. For every individual, finding the right combinations seems less like a science than an art. The fact that Forney continued to smoke pot and keep it from her therapist may or may not have contributed to issues like memory loss, but the reason why she concealed it ties into something she doesn't specifically discuss in the book, but which is there throughout: a fear of judgment and criticism.

Forney worries about people finding out that she's "crazy," until she owns her illness and gets support. She relates a number of incidents where people rightly call her out for being self-absorbed. She reluctantly tells her therapist about a weekend where she manically did cocaine, fearing embarrassment and judgment. Her therapist sagely replies, "I'm your doctor, not your parent." When Forney finally confesses that she is a pothead, she does so after realizing that whatever reasons she had for smoking pot (and there were many, even if some of them were a rebellion at sharing every inch of herself with her therapist), it's in some ways the last bit of track she needs to lay for recovery. All along, she finds ways to reconnect with people, finding understanding friends who know there are times that Forney isn't really capable of going out and doing something but instead needs someone to quietly be with her.

When Forney finally manages to level out, she's able to continue to use her formidable work ethic to return to that question of the relationship between mental illness and creativity. Her conclusion is that while creative people tend to be more susceptible to mental illness, the illness itself is not the cause of the creativity. Indeed, Van Gogh's paintings came during lucid periods, not during the depths of his depression. As Forney discovers during her own journey, it's an act of sheer will just to get out of bed, much less create a masterpiece. Certainly, leveling out allowed her to draw this 240-page comic, as well as to illustrate Sherman Alexie novels and release a couple of collections through Fantagraphics. She's a far more prolific and productive cartoonist now than when she was untreated. Forney notes, "I'd say my creative thought process is there whether I'm manic or stable ... maybe I have to believe this but ... stability is good for my creativity."

Having to believe this is a fact colors her actions and beliefs in retrospect. Yoga is now an important part of her life, so she depicts her initial opposition to it as foolish. Smoking pot ultimately proved to be harmful, so she depicts herself as stubborn and foolish in hiding it from her therapist. Glamorizing her mania and ignoring the effects it had on others is depicted as self-absorbed and selfish. The present rewrites the past, even if Forney honestly tries to confront some of these issues and talks about how she sometimes misses her manic states--just not at the cost it eventually incurred. Indeed, when she started therapy, she was no longer able to enjoy the manic states and was starting to have trouble differentiating between a "real" good mood and being elevated by illness. This kind of revisionist storytelling is only natural when one reaches a particular stopping point in telling one's own stories. The conclusions she came to may well have been completely different if she started writing the book immediately after finding a balance, if she wrote it during therapy, or if she decided to write the book ten years from now.

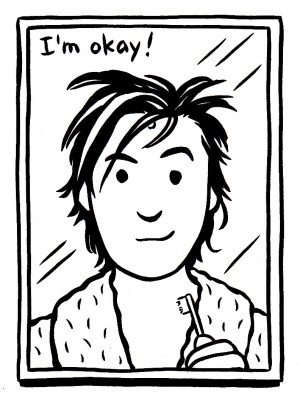

She concludes the book by saying "I'm okay!" as she draws a piece that literally addresses the issues I bring up here: talking to her younger self just after she was diagnosed, assuring her that everything will be OK. That last, assuring page is well-earned and far from glib, because the one thing Forney gets across in this book is that therapy is incredibly hard, transformative work. It's harrowing and forces one to reevaluate every aspect of one's life because old paradigms are crumbling. Forney went through that gauntlet and earned a hard-won stability that has allowed her to transfer the sheer effort needed to make it through therapy into her life and art. Marbles is not only a testament to that journey, but it's Forney's own way of providing "company" for others.