I was initially drawn to the Japanese edition of Hirohiko Araki’s Manga in Theory and Practice because of the two dudes looking like they were about to kiss, on the cover. They looked like sophomore versions of the Joestar family Araki is best known for creating, and I thought this was a pretty major coup of transition from homosocial straight to homosexual as far as mainstream manga was concerned.

Unfortunately for at least this reviewer, Araki doesn’t come out, nor do his characters. No cool 'ships…no secret past in yaoi. Manga in Theory and Practice is the practical vehicle for manga knowledge that its title advertises and Viz’s English edition provides a more sober cover and its raw translation is, for better or worse, un-calibrated for American readers.

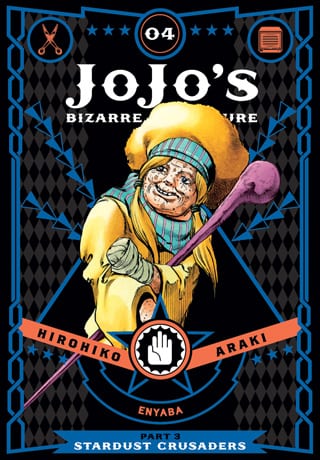

Hirohiko Araki was born in 1960 and has Type B blood, which I learned from Men’s Non-No (a populer Japanese men’s lifestyle magazine), which is to say Araki isn’t just a cartoonist but a sort of media personality; unusual in a camera-shy mangaverse. Yet his ability to talk about himself is a good indication of how unique he is and makes his style immune to imitators. Araki doesn’t teach you how to draw like him, but he does give us a clear picture of how he himself consumes manga and related media (anime, action films). His guide to manga comes replete with hand-drawn bullet journal-style progress charts, digital clip art, and samples of beautiful and wild storyboards from his best-known JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, which all demonstrate to the reader what they need to know about one very specific kind of mangaka: Hirohiko Araki. To a JoJo megafan…reading this book will not be unlike going to the Bubba Gump Shrimp Company; just fine for someone who wants shrimp and maybe for Mikelti Williamson if he’s feeling blue, but it will be a real treat for die-hard Forrest Gump fans.

He opens with the subtitle, “Returned to the Envelope Unread,” which reads as clumsily as he claims his failed submissions were in the beginning of his career. It is telling that he can’t describe his failures very well, because the leadfooted tone disappears when Araki starts discussing his triumphs. He is as good at talking about his greatness as he is poor at talking about his shortcomings, so I’d caution taking him too seriously when he waxes humble: His precision and planning behind proud achievements is as important on the confidence, even hubris, required to start any career in the arts. Araki’s methodology will do nothing if not impart confidence in craft. He calls his methodology the “Golden Way.”

As if clapping dust off his sleeves, he reverses hindsight and begins the methodology of The Golden Way with his next lesson: “Make Them Turn the First Page!” This is the breathless style Araki has become known for, the type of narrative he repeatedly endorses in the book. He cites examples from his own archive as well as from the classic Manga Canon (e.g. Dragonball Z). But the operative word in Araki’s guide book is “practice.” He repeatedly tells us to parse our favorite mainstream media, to understand narrative formulas and stylistic tropes that can work for readers when they start laying the groundwork of their own new works. He demonstrates by deconstructing his own favorite manga, some of which will be esoteric to anyone who doesn’t trawl in Japanese-language anime. Araki loves Hollywood action films, so he also cites a fair bit of North American tentpole productions: Terminator 2, The Godfather II, Kick-Ass…2. (It’s astonishing actually, how many sequels he deconstructs.)

The through line in all successful franchises, to Araki, is a strong goddamn character. This cannot be over-emphasized. The emphasis reflects Araki’s success with the dynastic narrative of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventures, if also the general direction toward which the manga paradigm has shifted. He goes so far as to say that in extreme examples, “compelling characters negate the need for story or setting.” As someone who has only ever failed to explain Araki’s storylines to the uninitiated, I daresay Araki doesn’t lie.

Because he uses Sazae-san (about a housewife, c.1948) and Chibi Maruko-chan (about a little girl, c.1986) as early examples of strong character-driven manga, it comes as a bit of a surprise when Araki advises on whether and how to include “female characters” in a story. He reassures us, in the year of our lord two thousand and seventeen, that: “Nowadays both men and women can become heroes. Up until around the 1980s, male characters had to be dynamic and take action and female characters had to be delicate and passive. But now, that’s no longer necessary.”

And on the one hand he says you can have a “macho female” like Sarah Connor in Terminator II, but: “I don’t pay any attention to the difference between men and women, aside from possibly setting them apart through clothing or makeup or sometimes including observations based on women around me, like when I’ve wondered How long is she going to dry her hair? or What is she doing in the bath for an entire hour?”

Finally, even though female characters can look and act like male characters, unless you have an urgent erotic message to tell, you might try to keep your story single-gendered. “As long as your characters are appealing, you could get away with a world of all men. You have nothing to fear.”

So in sum: a good manga requires no story, no setting, and no women.

…

The second half of Manga in Theory and Practice focuses on the more technical elements of manga drawing and style. Here again, he emphasizes the importance of reading canonical manga and learning from what you like. He cites Shigeru Mizuki and Kazuo Umezu to counterpoint emphasis of backgrounds versus emphasis of facial expression. So the trick is to lean in, but then not too hard, for therein lies the trap of mimicry and then derivative copying, which no one wants. Except maybe where it concerns guns.

As a translator, I hate to point out seams in translated English, and this one has less to do with the language than culture, but: the section titled “How to Draw Guns” feels a little irresponsible for an American audience, especially when Araki says that in the name of verisimilitude, in order to fully understand how firearms work, one should try one out. When he advised the reader to dismantle a gun and see how the bullet is fired when the trigger is pulled, I found myself saying out loud, “please do not buy a fucking gun,” to the imaginary teenage American reader. This gives whole new meaning to the phrase “trigger warning” and I’m not imparting it in hindsight, because if anyone can spot a fake-looking gun in a manga, it would probably be an American anyway. But please, don’t buy a fucking gun to become a better cartoonist. Araki is merely using guns as a example of something that personally drives him crazy when executed poorly. The point is that technical details of complicated machinery require extra research. He also explains how to articulate air and fire and suggests paying close attention when outdoors. So, warning: to depict nature one must also go on long walks.

In conclusion, Araki wants readers to know about his Golden Way to manga craftsmanship, without feeling beholden to any narrow specifications of what it means to make manga, and yet he wants only the best, most long-running manga out of you. In short, he has good ideas for how to make successful manga, but his ideas of success could use some qualifying. This is one lesson not taught in his art of mangacraft, perhaps better suited for his editors: know your reader. When Araki talks about sending his first winning submission to a shonen weekly at the age of sixteen, I can picture someone of the same age reading Manga Theory and Practice. They may be startled to see he had mastered a style so early on, but rather than be intimidated, a young reader will almost certainly be encouraged to start writing immediately. And that’s what makes Araki so special: he has a voice that is easy to relate with as a young reader. But then in his conclusion he says good writing is like drinking a fine single malt Scotch. I picture the 16 year old, emboldened to draw manga, studying guns, gulping a glass of Balvenie and spitting it out, confused. There’s some solace in knowing the teenager will know how to depict it accurately now.