We can only explain the surreal nature of coming across Zippy the Pinhead for the first time in the comics page of a local newspaper by pointing out that it shared the page with Beetle Bailey, Garfield, and The Family Circus. By contrast with those strips, Zippy was topical, refined, and weird as hell. The repetitions, juxtapositions, and coinages of Zippy's linguistic tics were hilarious and contagious. These aspects of the strip touched on the disaffection one felt when opening the newspaper and experiencing the disjunction between life at that moment in time and the official discourse of advertising and the news. The immediate question posed was: How did this get here?

Bill Griffith's new compendium, Lost and Found: Comics 1969-2003, partly sets about answering that question, compiling early and out-of-print stories unknown to even the avid Zippy fan. Griffith’s autobiographical introduction traces his seduction from painting into the base art of cartooning, his origins in the underground comics scene of the ’70s and the stages of his work, culminating with Zippy's near-breaches into the cultural mainstream. There are vignettes of hanging backstage with Manhattan Transfer and a healthy amount of dirt on the circa early-’70s San Francisco cartoonist scene. A major subplot is the quest to get Zippy on celluloid (perhaps starring Randy Quaid!). After a series of awkward meetings in Hollywood, strange coincidences, and rewrites, the cartoonist concludes: "I think I now know why a movie was never made ... it was because I couldn't relinquish control of Zippy. In the end, I couldn't compromise." A twist of fate led to Zippy being sought out by William Randolph Hearst's grandson for the San Francisco Examiner, and later reaching a national audience through King Features Syndicate. And with that, Griffith turned his energy away from the languishing underground and towards making Zippy a daily blast of the subconscious.

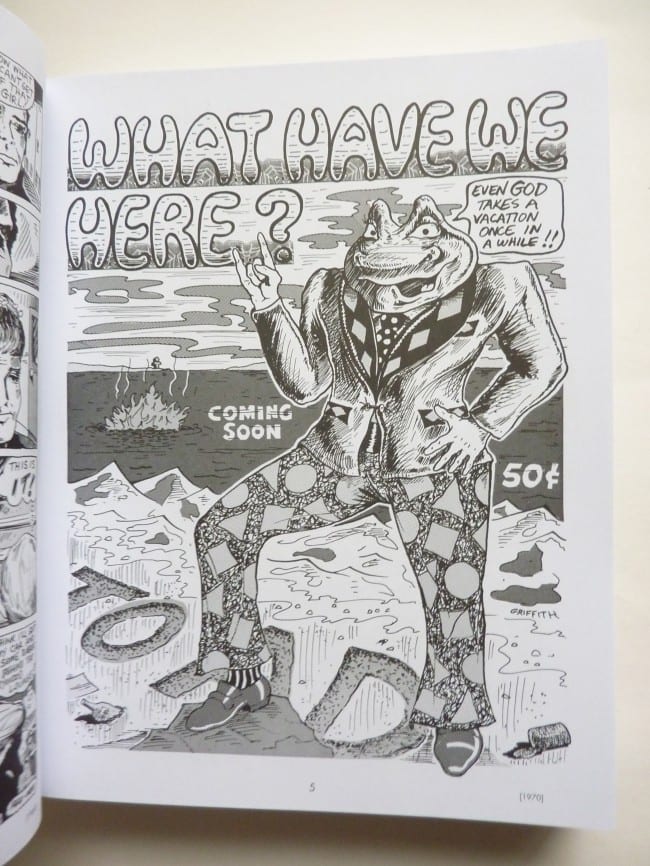

While the introduction tantalizes us with the path not taken of a Zippy blockbuster, Lost and Found wishes to present, in completist fashion, all the other avenues that Griffith actually did stroll down. It is educational to see the evolution of Griffith's killer crow-quill line, and his abandonment of a sometimes clumsy and thick outlining style. No matter what period, the panels always brim over with the data of a barely reigned-in imagination.

According to the talking cat on page 239, Zippy is Griffith's "best character." But by the mid-'70s Griffith had generated a small cast of regulars he used in his strips (appearing in anthologies like Arcade and Griffith solo titles such as Tales of Toad) to inhabit and refract popular culture. Characters such as Mr. Toad, Claude Funston, Cherisse Fisk, and eventually Zippy, are the players in the ‘70s strips, which account for two hundred pages of this tome. These stories usually begin as familiar pulp pieces—a romance, western, or detective story—and wind up messily deconstructed through the anarchic wordplay and antics of Griffith's troupe. A novel's worth of Mr. Toad strips is here. Toad parades his bad attitude as a painter, a porn actor, and a vaudeville performer. A number of fabulously carnal strips, many from the Griffith co-edited series Young Lust, are a revelation, especially if your existing mental image of Griffith was of the ultimate intellectual cartoonist. Cut-out porn stars Randy and Cherisse test whether one can get turned on by two-dimensional images, some muscle-bound heroes duke it out on Mars in a Richard Corben parody, and Hopalong Cassidy must have done something to deserve the skewering he receives at the hands of two lingerie-clad she-bandits. Not to be missed are Claude Funston's gauche but well-intentioned misadventures with strippers, sheep, and Tammy Faye Baker. A smattering of interview strips with such figures as Mike Judge and Tom Jones round out the book.

According to the talking cat on page 239, Zippy is Griffith's "best character." But by the mid-'70s Griffith had generated a small cast of regulars he used in his strips (appearing in anthologies like Arcade and Griffith solo titles such as Tales of Toad) to inhabit and refract popular culture. Characters such as Mr. Toad, Claude Funston, Cherisse Fisk, and eventually Zippy, are the players in the ‘70s strips, which account for two hundred pages of this tome. These stories usually begin as familiar pulp pieces—a romance, western, or detective story—and wind up messily deconstructed through the anarchic wordplay and antics of Griffith's troupe. A novel's worth of Mr. Toad strips is here. Toad parades his bad attitude as a painter, a porn actor, and a vaudeville performer. A number of fabulously carnal strips, many from the Griffith co-edited series Young Lust, are a revelation, especially if your existing mental image of Griffith was of the ultimate intellectual cartoonist. Cut-out porn stars Randy and Cherisse test whether one can get turned on by two-dimensional images, some muscle-bound heroes duke it out on Mars in a Richard Corben parody, and Hopalong Cassidy must have done something to deserve the skewering he receives at the hands of two lingerie-clad she-bandits. Not to be missed are Claude Funston's gauche but well-intentioned misadventures with strippers, sheep, and Tammy Faye Baker. A smattering of interview strips with such figures as Mike Judge and Tom Jones round out the book.

The author gradually enters this fractured universe as a bit player, then as observer/participant. He eventually breaks with the medium's rules to not only address, but to give orders to the audience. He portrays himself as a subjective, unreliable narrator, and as a slightly uptight, obsessive guy. In "Cast of Characters" from 1980, Griffith (consigned to a hilarious "Underground Cartoonists Retirement Center") is confronted by his own creations. Each one declares itself to be one aspect of the author's conflicted identity. Mr. Toad is a "domineering father figure," Claude Funston is an expression of his "frustrated libido," Cherisse Fisk an "engulfing bourgeois bitch." These experiments emphasize that he has a point that he wants badly to make clear to you the reader: that the crazy world represented is the one you live in. Only Zippy seems external to Griffith's psyche, arriving separately on a beam of light with the utterance, "I represent a sardine..."

Zippy is a holy fool, an innocent. He has a simple relationship to the modern culture that so disgusts and fascinates Griffith: he is distracted and excited by it. "Life is a blur of Republicans and meat," quoth Zippy. With his short attention span, irrational appetites and unquestioned assimilation of slogans and sound bites, Zippy is an average American citizen. Zippy's influence on the culture at large can be charted by the ubiquity of the phrase, "Are we having fun yet?" His heyday in the ’80s and ’90s was a direct reflection of the absurd consumer culture that was rapidly becoming inescapable. Griffith uses every tool at his disposal to get across the strangeness of this, and his body of work charts the progress of irony over the last four decades. For the compulsive Zippy reader who spent the ‘90s stumbling around muttering "Boutros Boutros-Ghali," the book points out just how much more inured to absurdity we have since become.

Lost and Found is the sort of retrospective project that begs summary statements. The introduction reads like a compressed memoir. The book, while extremely dense and a bit overwhelming to read, testifies to Griffith's heroic output of underground comics, and his commitment to a lifetime of making work that is challenging, inventive, and beautifully drawn. His signature narrative discombobulation and linguistic elasticity unite all these disparate pieces into a cohesive statement of surprise and protest. It is ridiculously quotable. Also, it is very funny. Lost and Found delivers wholesale entertainment value with a socially redeeming dose of satire.