Karl Marx famously noted of history that events and figures reappear “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”. In fact, as is driven home in Derf Backderf’s Kent State, an exhaustively researched graphic novel on the massacre of students by Ohio national guardsmen in May of 1970, it repeats itself ad infinitum, but merely as tragedy.

The slaughter of students at Kent State is now the stuff of Boomer lore and pop culture (the book’s subtitle, Four Dead in Ohio, is the damnably catchy hook of “Ohio”, the famous song written by Neil Young and recorded by CSNY only two weeks after the killings), but from the first page to the last, Backderf is on a mission to remind us that there is simply nothing new under the sun. While the book was designed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the massacre, which took place only a few dozen miles away from his childhood home when he was all of ten years old, he had no way of knowing that it would become intensely, unforgettably relevant again only a few weeks after that anniversary when the country exploded into an uprising against white supremacy and police brutality sparked by the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota by cops.

The details of the story ought to be burned into the brain of Boomers and even a lot of Gen Xers, but for younger readers, it might be quite a revelation to learn that over a dozen students at an unassuming Ohio university were mowed down by armed amateur soldiers, resulting in four deaths and a handful of permanent, crippling injuries. While tensions were high over recent labor strikes, street actions, and student protests against the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the day’s protest had been peaceful, and fewer than half of those shot by the guardsmen were even involved; many were simply walking to and from classes on a day when the campus was open despite calls to shut it down.

The fact that the students were required to be in a situation where their lives were endangered is only one of roughly a thousand details that echo through time and seem even more relevant now, in the light of nearly identical behavior by cops during the current uprising, than the author ever intended. Absurd rumors of organized, violent gangs of terrorists prowling the towns; police and military forces led by self-aggrandizing incompetents whose only solution is to escalate; protesters being herded into traps where they can be brutalized with no chance for escape; a compliant media repeating the lies told by those in authority to escape culpability; property being valued over human life; it’s all depressingly familiar, to the extent that the police today are literally using identical tactics as the Guard used a half-century ago.

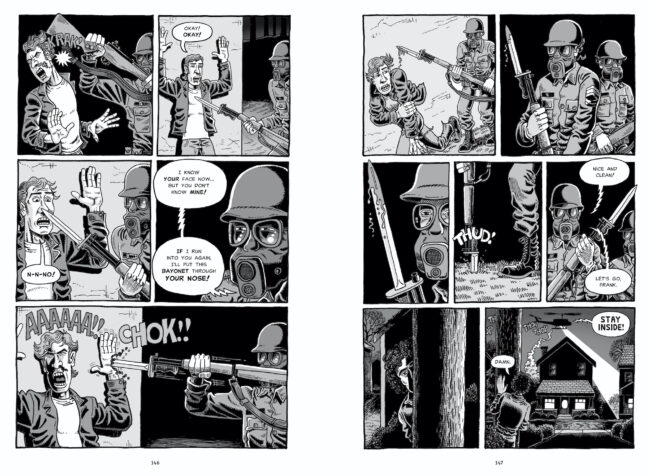

Backderf’s narrative, rendered with great detail in his familiar exaggerated style and thoroughly detailed in every panel, sometimes gets a bit heavy-handed. The dialogue, except when drawn from actual contemporary accounts, tries to compress a lot of background information, with the result that it often feels like he’s trying to catch the reader up on what happened in a previous story they hadn’t bothered to read. His deep dive into the background of the political situation that led to the massacre is informative but sometimes intrusive, and there’s never a moment that allows for rest and the ability to absorb the players as real people. The only time the story is allowed to breathe is at its end, in the manner of so many biopics that cram a little too much information in at the expense of its characters’ depth.

Backderf’s narrative, rendered with great detail in his familiar exaggerated style and thoroughly detailed in every panel, sometimes gets a bit heavy-handed. The dialogue, except when drawn from actual contemporary accounts, tries to compress a lot of background information, with the result that it often feels like he’s trying to catch the reader up on what happened in a previous story they hadn’t bothered to read. His deep dive into the background of the political situation that led to the massacre is informative but sometimes intrusive, and there’s never a moment that allows for rest and the ability to absorb the players as real people. The only time the story is allowed to breathe is at its end, in the manner of so many biopics that cram a little too much information in at the expense of its characters’ depth.

But he can’t be faulted for trying. For obvious reasons, Backderf focuses heavily on the four students who died: the determined activist Allison Krause, the reluctantly radical musician Jeff Miller, the kindly and apolitical Sandy Scheuer, and Bill Schroeder, an ROTC officer in training who was saved from being shot in Vietnam by getting murdered by his own countrymen. Villains also emerge; while it’s never been determined – thanks to plentiful lies and obfuscations by officials – who fired the deadly shots, plenty of blame accrues to the out-of-control guard commander Robert Canterbury, a washout pogue who seemed determined to make every aspect of the situation worse. Particularly unforgettable is Kent State student Terry Norman, a professional snitch for the FBI who was well-known on campus for his aggression and incompetence. The book’s length still doesn’t allow them to emerge as naturalistic figures, but their presence alone is an illustration of what a complete disgrace it was that any of this happened to begin with. Backderf takes pains to illustrate that the victims weren’t the savage revolutionary Weathermen they were made out to be by the authorities, but even if they had been, they wouldn’t have deserved to be shot dead on the ground for protesting an immoral war.

Once the shit really starts to come down, Backderf compresses the narrative action beautifully, almost constituting another book within a book that has all the desperate energy, exhausting adrenaline, and overwhelming, enervating tragedy of Paul Greengrass’s similarly themed film Bloody Sunday. It reduces time to a stretched-out moment (thirteen seconds, in fact, during which the guardsmen rained 67 bullets on the helpless crowd) that justifies all the buildup that’s come before. It’s a truly alarming and cathartic conclusion that makes up for the occasional clunky moment that precedes it.

Once the shit really starts to come down, Backderf compresses the narrative action beautifully, almost constituting another book within a book that has all the desperate energy, exhausting adrenaline, and overwhelming, enervating tragedy of Paul Greengrass’s similarly themed film Bloody Sunday. It reduces time to a stretched-out moment (thirteen seconds, in fact, during which the guardsmen rained 67 bullets on the helpless crowd) that justifies all the buildup that’s come before. It’s a truly alarming and cathartic conclusion that makes up for the occasional clunky moment that precedes it.

What Backderf couldn’t have anticipated, though, in anything but an abstract and theoretical sense, is how deeply and profoundly his approach, and his admirable exploration of the particulars of the massacre, from the tense confrontations that preceded it to the legal and cultural wrangling over its legacy that followed, would resound upon Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio’s release. It is this determination to make a whole living world out of an event that is often presented in the form of a single still photograph that often carries nothing but Boomer nostalgia. By buying into the details so heavily, he makes a story that means something more today – and serves as a warning as we see the story repeated, again and again, every day, always as tragedy.