1.

Legs, eyes, head, boat––This is the opening gambit, a wordless passage of largely stacked frames. A boy on a stationary boat observes the approach of three boats carrying military personnel.

It’s the army patrol. He launches a small rock at one boat. The rock misses and plops into the water.

When an armed guard raises his weapon in threat, the boy flees.

The backdrop is implicitly either Dal Lake or River Jhelum, a scenic waterway that runs through Srinagar, the Kashmir Valley’s summer capital. The attack is perfectly reasonable. No one wants his or her paradise on earth turned into a police state.

“Tell me, what was Kashmir like in your time?” So Ali, a young tearaway, asks Mushtaq, the stone-throwing boy of the book’s opening sequence, now a prematurely middle-aged and god-fearing Muslim rather than fearsome rebel.

Sitting in the dark but calm shadows of his prison cell, Mushtaq begins to tell the story of his life to Ali, from his birth in 1971, through his radicalization and then his incarceration and reconciliation. His story is also meant to be the story of Kashmir, personified, over the previous thirty-five or so tumultuous years.

These two passages of rebellion and incarceration illustrate the central motivations of Kashmir Pending (2007), a graphic novel by Naseer Ahmed and Saurabh Singh. Based on a true story, the novel charts the life and transformation of a Kashmiri Muslim called Mushtaq, an insurgent who gives it all up to run a tea stall. The novel was published in New Delhi by Phantomville, a now defunct press co-founded by graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee and filmmaker Anindya Roy, both of whom also contributed to the production of the graphic novel. Through Mushtaq, the novel, which is largely documentary in graphic format and execution, grapples with the issue of political impasse in contemporary Kashmir, namely that many Kashmiris want to secede. Specifically, then, Kashmir’s political recognition as an autonomous state is what’s ‘pending’ in the region, as it is in Ahmed and Singh’s novel.

Before moving on, it’s vital to understand that any scrupulous commentary about Kashmir, published or spoken, is a hazardous project. In India, openly questioning the state hardline––that Kashmir is an integral part of India––is simply not done. You’d be called crazy for doing so. You could be accused of seditious intent and threatened with a fine or jail time, as internationally fêted writer Arundhati Roy recently discovered on speaking out. Or, if you are Prashant Bhushan, a top-order rights activist and lawyer advocating plebiscite in Kashmir to determine what Kashmiris want, two right-wing goons will walk into your Supreme Court lawyer’s chambers in New Delhi, drag you to the floor, and brutally kick you in the chest. Likewise, the state closely manages voluble activists and observers of Kashmir, foreign and Indian, as in the case of David Barsamian, a lefty US radio-journalist who was recently deported on arriving in New Delhi. Similarly, Gautam Naulakha, civil rights activist and Convenor, International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Kashmir (IPTK), was deported to New Delhi on arriving in Srinagar. In other words, Kashmir Pending is an inherently brave enterprise by virtue of its very existence, which also calls for the courage to fully grab and cogently address, however thorny, the problem.

2.

Kashmir is the commonest name for what is actually Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), a north-western Himalayan territory that straddles snow-capped mountains, gorgeous rivers, and stunning views of fog and mist rolling across valleys. Kashmir consists of five regions––Jammu, the Kashmir Valley, Ladakh AND Azad Jammu and Kashmir and the Northern Areas––of which India controls the first three under the banner “India-controlled Jammu and Kashmir” (IJK). Pakistan controls the latter two under the banner “Azad” or “Free” Jammu and Kashmir (AJK). A small area called Aksai Chin is occupied by China. IJK and AJK are collectively referred to as Kashmir (J&K), and the genesis of the ‘Kashmiri problem’ typically dated to August 1947, the year the Indian subcontinent threw off British rule and divided into India and Pakistan.

Late in 1947, during communal massacres between Muslims and Hindus and fighting between army, militia, and citizens, the princely state of Kashmir was incorporated, not into Pakistan, but India. Still, the absence of a plebiscite remained a sticking point. The U.N. prescribed referendum, which India promised but reneged in fulfilling, would have identified whether Kashmiris wanted to join India or Pakistan, or secede and form an independent state. Thereafter, India and Pakistan fought several wars over Kashmir’s rightful ownership. In 1949, following a truce, Kashmir was respectively divvied between India and Pakistan controlled territories, India acquiring the most valuable and scenic chunks. Subsequent wars in 1965 and 1971-72 slightly altered these borders, ending in the 1972 ceasefire. More recently, in 2001, 1 million Indian and Pakistani troops were deployed across each other at the Kashmiri border known as the Line of Control (LoC), whereafter Kashmir has become the most militarised micro region in the world.

Beyond this plum role in the cross-border tug of war, Kashmir is also the site of an internal conflict between the Indian state and Kashmiris fighting for independence. Generally speaking, Kashmiris in the Kashmir valley are more likely to support secession than those in Jammu and Ladakh. For unlike Jammu (largely Hindu) and Ladakh (largely Tibetan Buddhist), the Kashmir valley is dominated by Muslims, who commonly view the mainly Hindu India as a natural enemy. This fracture alone has made the Kashmir valley the natural homeground of two linked affections––autonomy and pro-Pakistan bias, both of which unavoidably link to insurrection.

The most efficient upwelling of the past two decades began in 1989, a watershed that many consider the natural outcome of government coercions from two years earlier. In 1987, the political party that actually lost the Kashmir legislative elections, but which parroted the government hardline on Kashmir, was declared the winner. Government officials pitched in to make this possible, while to suppress reaction, two key members of the originally winning party were incarcerated without trial. These were the party’s leader and election manager, both of whom acquired military training and ordinance during subsequent exile in Pakistan. On returning to India in 1989, one became commander-in-chief of the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM), Kashmir’s most powerful insurgent movement, armed and funded by Pakistani military authorities. The other became a leading member of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a pro-autonomy guerrilla movement that kicked off insurgency in the Kashmir valley.

Retaliation followed swiftly. Almost overnight, in 1989, the India government turned the alpine Kashmir valley into a police state, rife with curfews, forced police entries, and military supremacy. Since then, an estimated 80,000 resident Kashmiris have died. Accounts gathered by civil rights societies report human rights violations by the police and military that include gang rape and forced disappearances. In 2007, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) in Kashmir claimed 10,000 people have disappeared in Kashmir since 1989, largely abducted by the Indian army, which labels them foreign guerrilla fighters. Finally, this year, the State Human Rights Commission (Kashmir) admitted the existence of some 2730 bodies in unmarked graves across three Kashmir districts. More than 500 of these bodies were identified as local Kashmiris, not foreign insurgents. Making a fitting corollary to the graves are the officially-estimated 1500 Kashmiri women (6000 reported by civil groups) dubbed “half-widows”, half because their disappeared husbands have yet to be pronounced dead. This uncertainty disqualifies them from ex-gratia compensation and re-marrying for seven years and prevents them claiming property rights—a predicament that marks only one facet of the limbo at large latent in Kashmir Pending’s narrative.

3.

Because Kashmir Pending is set smack in the middle of Kashmir’s difficult political history since the 1970s, one might presume that the events, strategists, and executors of insurgence in the book allude to recognizable real-life counterparts. However, barring one date, the narrative neither specifies the timeline nor identifies real names of organizations and their leaders. The story is driven by Mushtaq, who in Chapter 1 is a veteran inmate of Srinagar Prison, where he one day he meets young Ali, newly transferred from a high security prison.

Mushtaq is a native of downtown Srinagar.

He was born in 1971, which marked the conclusion of the Indo-Pakistan war (1970-71), the consequent secession of East Pakistan from Pakistan, and the founding of Bangladesh with India’s help. The book depicts his happy childhood against a restless backdrop of perennial political unrest. Mosques were settings for anti-government speeches.

Collisions between locals and police broke out during street protests. Pakistan, which had always represented a kindred spirit, newly became a political magnet. The Indian state assigned Kashmir to BSF (Border Security Force) control. Presumably, this is 1989, the year insurrection was set into motion. Door-to-door searches, police abductions, witch-hunts, and public killings of civilians became common law.

Prohibitions on listening to Pakistan radio took effect. Finally, in the wake of state-endorsed power cuts, water shortages, and police attacks on hallowed Muslim sites, civilians broke rank and began taking cogent steps.

This traumatised milieu sets the scene for Mushtaq’s concrete transformation in Chapter 2 from a fiery sixteen-year old who dabbles in violent protest to local hero after his first brief stint in prison.

In Chapter 3, Mushtaq makes contact with the leader of a pro-independence movement, enlists in a clandestine group, and later crosses into Pakistan-administered Kashmir where he trains in military soldiering. Quickly disillusioned with his cohort and troubled by the rise of a different group called the K force, Mushtaq alone makes for Afghanistan where life among Afghan fighters resuscitates his former idealism. Later, in Chapter 4, Mushtaq returns to Srinagar, where he is redrafted into Kashmiri resistance, now fully subsumed under the K force, Srinagar’s unofficial administrator. Infighting, K force treachery, and the killing of his close friend Aziz collectively resolve Mushtaq to give up rebellion. The Endgame chapter depicts the defining moment, which occurs at a military checkpoint. Mushtaq, loaded with a bagful of grenades, has to choose between escape at the cost of killing a few police officers or capitulation. He relives his first hatred of the police when as a boy he had thrown rocks at them. This time, he opts for surrender and is jailed.

The epilogue covers Mushtaq’s life post-prison. One day, he meets the newly released Ali who is readying himself for a suicide-bombing mission. Mushtaq’s life is tamer. He owns a small tea and snack shop where he regales clients with stories about his violent youth. In camera, he recollects old conversations with Ali, who for him represents the tragedy of Kashmiri youth brainwashed into espousing force. Here, Mushtaq’s declaration “I do not want any more innocent lives to be lost in the cross fires of my war” neatly concludes the novel’s evolving principle of pacifist resistance.

4.

The drawing in Kashmir Pending is documentary and iconic. Many panels are pointedly reminiscent of photographic stills familiar from headline stories, some an obvious outcome of freehand artwork by the artist Saurabh Singh based on photographs taken by the writer Nasser Ahmed.

This prototype generates effects analogous to a neutral scrapbook of events, which is rather odd coupled with what is ostensibly a personal narrative of rebellion and renouncement.

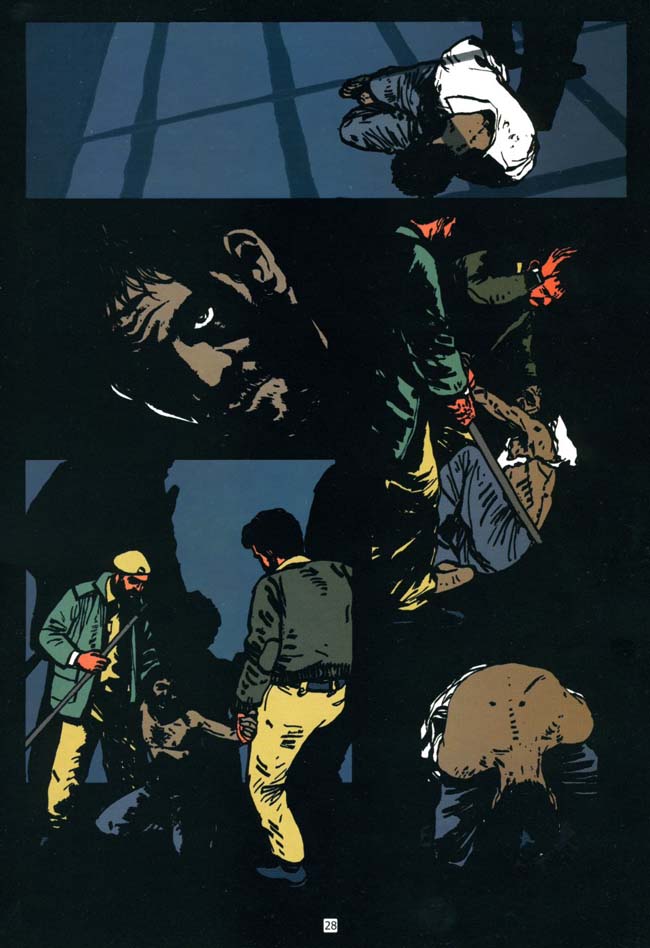

Nonetheless, according with Mushtaq’s dark account, the drawing obeys a surfeit of black. In some instances, severe line and pure shadow combined with minimal modelling remind emphatically of Mike Mignola’s Hellboy atmospherics. This formal preference is especially effective in scenes of extreme violence and bodily pain, such as Mushtaq’s first encounter with prison and torture.

In general, however, figures and background are rigidly bound by inelastic black outline steeped in initially arresting, even pleasing, dark, saturated colour. Solid orange, green, mustard, charcoal grey, and red provide surface immediacy, explicitly effective in Chapter 1’s opening panels. River Jhelum is a tomato red plane, Srinagar a city inked in black on its shores. The minimal palette in this passage seems to evoke the paradox of prettiness and dread before the story fast tracks to ugly. Decisive colour contrast, gradually darkening gutters, combined with some shifts in scale and perspective, from close-up and full body shots to overhead views and low angles, occasionally across panels within a single page, provide numerous visually intense doses.

Some scenes, such as a man shot and killed by police fire, are cleverly designed to capture the sensory fracture Mushtaq experiences in witnessing violent death at close range.

Eyes see spent shells. Eyes fix on shattering body. Dying man hawks and spits in the throes of death. Mouth screams in lone anguish. These images are also among the book’s most memorable scenes. They inject a welcome psychological zest into the flat documentary framing, which adeptly reports on spaces and scenes but does not incarnate or distinguish the primary subjective position, i.e. Mushtaq.

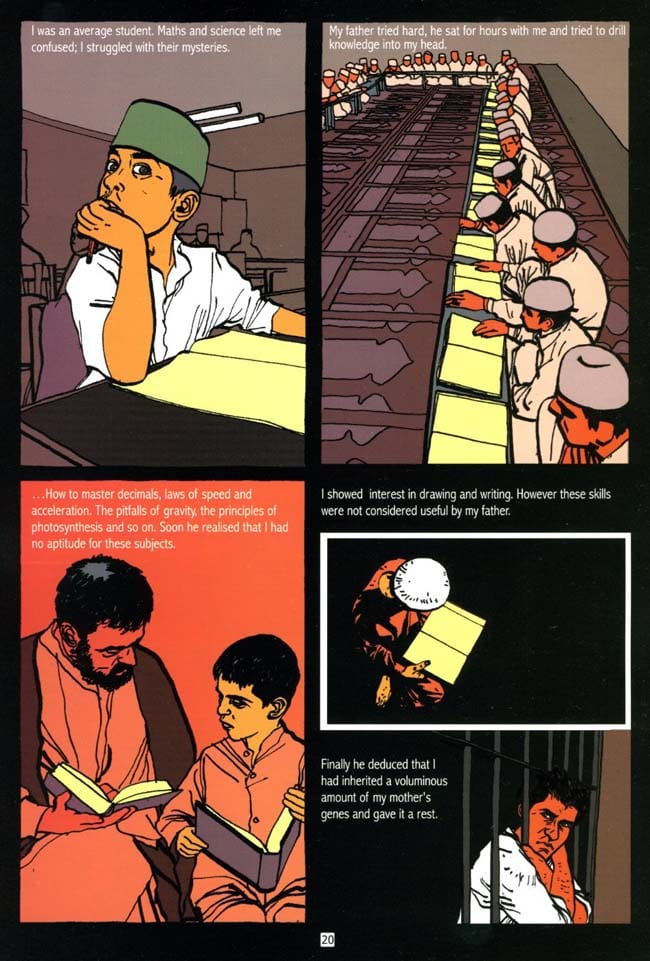

Weak characterisation is perhaps most acute in how characters look. Minor facial and physical distinctions play out only nominally in favour of anatomical coherence. Mushtaq, for instance, is a good looking man in his late 30s, lips gravely set, eyes intensely fixed on what we should understand as inner turmoil––but then so are so many other male characters in this book, including Mushtaq’s father.

In contrast, panels featuring clusters and crowds, such as protesting crowds, students bent over desks, and uniformed police standing guard, end up decisively more vivid and descriptive than portrayals of individual characters, barring some exceptions that literally pop out of the page. Chapter 2’s opening panel, for instance, is a touching portrait of a very young Mushtaq eyes-wide dreaming bored out of his skull at school. It’s also one of very few moments in which detail trumps visual uniformity, which as it hastens reading also flattens and abbreviates Mushtaq’s evolving psyche, and through it how he sees the world. All things considered, a vastly slower pace teasing out details expressed by a more flexible graphic style across varying content––history, locale, and social–-would have definitely made for a more engrossing read. Instead, the dark world and cookie cutter aesthetic barely lets characters show their true colours, let alone adequately speak their minds.

From the outset, Mushtaq’s testimony is all too clipped. Scant dialogue and non-existent sound effects in what is a very noisy world of protest, guns, and violence frames Mushtaq almost as a flaneur, only spasmodically susceptible to the messiness of direct verbal contact. Pithily expressed and emotionally anonymous, his world is a catalogue of almost mute pictures. This effect might be intentional and well meant, though given the highly selective press coverage of the region why presume that readers, even Indian ones, know very much about Kashmir. Beyond this is all happening in Kashmir one never gets a comprehensive sense of physical environment, cultural complexity, or the urgency of limboland Kashmir, which is ill-understood even among many newspaper reading literate Indians outside the region.

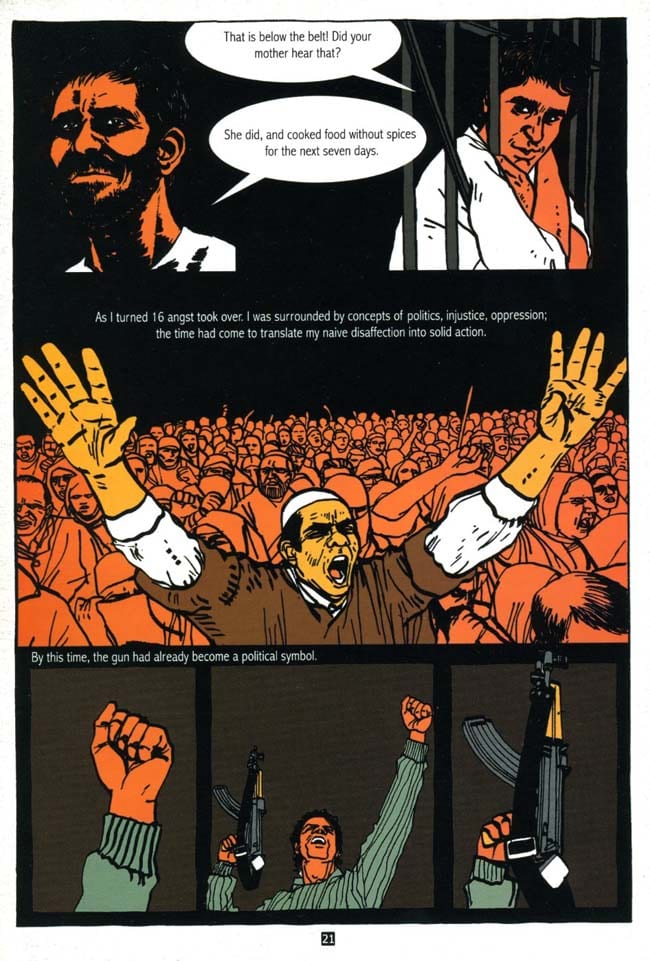

For starters, Mushtaq could have fully exploited the space opened up by Ali’s question, “Tell me, what was Kashmir like in your time?” and articulated history and politics as precisely as possible. Instead, his reserve––constituted by minimal dialogue, whittled down descriptions, and bridled emotion––not only fails the question, thereby showing up Ali as a hollow narrative device rather than a full-fledged character. It also obscures the causes of Kashmiri insurgence. Likewise, simply indicating the overlap of Mushtaq’s active rebellion at the age of 16 and the rigged elections of 1987 would have edged his generic account of political woe with the importance of present-day provenance. Here, achieving immediacy is important, firstly because Kashmir’s problem is too severe and tragic to make do with woolly parallels. Secondly, specificity helps to maintain the purity of character motivation. One representative panel shows the easy bleed between reading rebellion as unwarranted violence. The image features angry crowds. At the centre is a screaming man wearing a characteristic topi, a cap worn by Muslim men.

Mushtaq’s caption says, “As I turned 16 angst took over. I was surrounded by concepts of politics, injustice, oppression; the time had come to translate my naïve disaffection into solid action.” The caption is true in feeling, as are so many statements Mushtaq makes, but it lacks the vital details that would justify Kashmir’s gripe, as well as his own in his capacity as an angry Kashmiri.

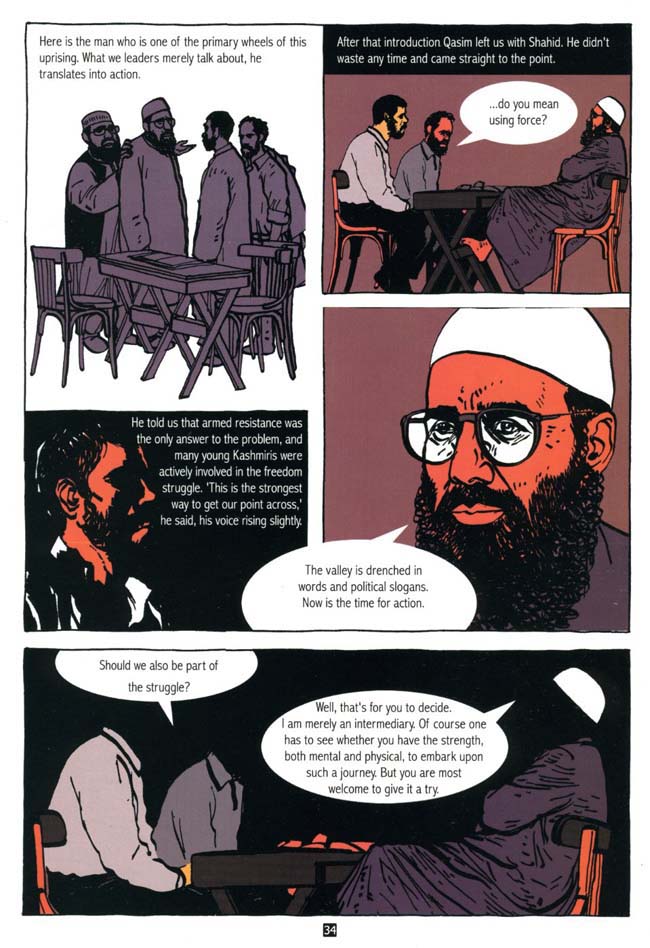

The same goes for ideology. It’s everywhere but feels tacked on, mainly because key characters lack human depth. Shahid, for instance, Mushtaq’s most important interlocutor in the road to active armed resistance merely declares his position on armed resistance without preface or ekphrasis.

“The valley is drenched in words and political slogans. Now is the time for action.” If the sloganeering is spot-on, the laconic dialogue plays down the scary appeal of demagogues. One might easily equate insurgence with gratuitous anarchy. In fact, Shahid is most likely a stand-in either for the election manager or the leader of the party that originally won 1987 elections. Both later went on to head up Kashmir’s insurgent movements. Making that link, or suggesting a possible one, without having to name organizations, would have made for a fantastic eureka moment, evoking an instant bond with Mushtaq’s angry young man character and consequently redeeming the good things about insurgency in Kashmir.

Other types and situations also await a more human shape and audible voice. But in Mushtaq’s narrative, encounters between protestors and police are portrayed as silent iconic scuffles devoid of speech and sound effect. Likewise, the quiet scene of inquisition by police outside people’s homes is at odds with the daily siege Kashmiris endure. There are many such real-life reports. Take the story of Bilquees Begum, a woman whose husband disappeared before her eyes on July 20, 2003. There was a wedding party at their house. The army knocked on the door, flooded the house, disrupted the party, and asked for the eldest son of the family to step out of the crowd. This happened to be Bilquees’s husband Ahmed, who was taken for questioning with the promise he would return the following day. He never did. Bilquees has not been silent. She has looked for her husband, asked questions, protested, and gathered legal documents recording the disappearance. Her story has recently made it to the pages of The Huffington Post in a story by Mallika Kaur. A different, plainly horrific, by-product of military occupation features in a well-circulated incident of members of the Indian army gang-raping 30 women in Kunan-Poshpura in the Kupwara district of the Kashmir valley.

Transcendent sovereigns––that’s the factual status of India’s military in Kashmir, in light of which Mushtaq’s portrayal is shockingly deadpan (Fig.7). “Troops could arrest, kill or rough up any person on mere suspicion. The state was under the direct rule of New Delhi and the army was teethed with enormous power.” Both these statements couldn't be more exact were they not attached to two terror-inducing acronyms. Indeed, Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), operative in Kashmir since 1990, and the Public Safety Act (PSA) grant the military the power to shoot to kill and arrest anyone on mere suspicion. They also exempt military personnel from persecution for extra-judicial crimes, rape, torture, and illegal detentions, which writer Pankaj Mishra in a piece in The New York Times described as making “the excesses at Abu Ghraib seem like a case of high spirits.” Together, AFSPA and PSA are double-edged swords. They licence a trigger-happy military and provide India a veneer of protection against contravention of international law, such as the Geneva Conventions.

4.

Any historical reportage is bound to highlight some stories over others. But Kashmir Pending’s allergy to joining the dots between the nuts and bolts (dates and names) of state suppression, an absent plebiscite, and full-blown insurrection makes room for very dodgy conclusions. Surely, Mushtaq and his cohort are no more than a bunch of pesky (Muslim) militants, and good on Mushtaq for quitting that terrible business. Personally, little else is inferable from the depictions of long tunics, beards, white headgear, and scenes of praying militants. Prefaced earlier by scenes of prayer and protests within mosques, Mushtaq’s insurrection easily translates as the natural extension of Islamic pathology (Fig.6). This is a commonplace assumption, no less in India where even Kashmir’s genuinely secular pro-autonomy movements have been tarnished by equation with Islamic terrorism.

Kashmir is more or less a police state within the world’s most populous democracy. These two facts free-float in Mushtaq’s account, though lacking cataclysmic synapse Kashmir, despite its unique political predicament, sinks like dead weight into the general ruck of upheaval in the world. To shock and teach (or to what end is a story of bad becoming good?), Kashmir Pending’s tableaux of guerrilla warfare must first invite empathy, probably achievable by a less guarded raconteur, perhaps taking a leaf out of Joe Sacco’s Sacco in Palestine. Sacco’s commentary interspersing conversations with numerous characters closes in on various debates around Palestine and Israeli occupation, with Sacco nowhere invisible when he wants to make a stringent point, or backtrack to clarify fallacies. Led by the casual but keen, and always affected narrator––be it with humour, astonishment, or horror––Palestine becomes a go-to model of quality political reportage that is equally absorbing as a story, in the most conventional sense of the term.

For the most part, I do not see objective documentary graphics and terse personal memoir marrying happily in Kashmir Pending. I expected a more sound depiction of the Kashmir story, and a more credible vision of human decision. Mushtaq ending up running a tea stall is a far too lovely finish to a cup of tea embittered by unmarked graves, hundreds of political prisoners, and decades of militarisation. The narrative provides no prognosis, no active, pointed critique, and no tolling bells for Kashmir. Ending the book on peace (integration) not war (separation from India) robotically snuffs any whiff of controversy and potential backlash. True story notwithstanding, Mushtaq’s eventual pacifism therefore reads less organically than it should. No doubt, Kashmir Pending marks a general peril attending any good-willed reportage on Kashmir but takes no specific risks itself. Clearly, I wanted this book to have done and been much more. This is an unfair criticism of any project that knows itself, and this one surely does. But knowing yourself is not the same as penetrating the world.