In his introduction to this collection of short-form comics journalism pieces, Joe Sacco undertakes a self-professed manifesto regarding the form. In particular, he takes aim at the sacred cows of U.S. journalism — "objectivity" and "balance" — and essentially skewers them as the empty concepts that they truly are. Sacco is careful to note that this doesn't mean that doing research, getting quotes right, and thoroughly investigating claims made in the course of a story aren't important. In fact, he would say that they are essential elements of a good story. What he's driving at is that the concept of objectivity in journalism is impossible because there is always a subjective viewpoint behind every story. This is why he is careful to draw himself as part of the story: not to draw attention to himself as an important figure, but to reveal his biases and point of view as transparently as possible, to let the reader know that there's a person behind the reportage. He quotes Edward R. Murrow saying, "No one can eliminate prejudices--just recognize them." He deftly skewers the idea of balance for its own sake, saying that just because there may be two points of view regarding a subject doesn't mean that the truth lies somewhere in between them. This is the essence of what drives him to report on the things that he does: to give voice to those who are suffering and silenced.

One of the reasons why so-called objectivity is perhaps less important for Sacco is that he's not on a breakneck news-cycle. He generally spends a great deal of time in an area when trying to find his story, which allows him more time to research, get the lay of the land, ask a lot of questions of a lot of people and build relationships. This is a big reason why Safe Area Gorazde and Footnotes In Gaza are masterpieces of both comics art and journalism. It's also why the longer pieces in Journalism are the most interesting. "The War Crimes Trials" (a coda to his work in Eastern Bosnia) and "Hebron: A Look Inside" (a job for Time magazine) are two of the weakest stories in the book. In the former, he lacked the kind of access he wanted in attempting to get across why the genocide trials of key Serbs were so important, which makes Sacco's voice the loudest in a story where other voices need to be heard. This is a weakness that Sacco himself acknowledges in his notes. In the latter story, Sacco claims that he froze up when given a chance to work for Time, and the result was the sort of wishy-washy "balanced" story about Jewish settlers in Hebron that he generally avoids. He even removes himself from the story even as he leaves in his usual conversational narrative captions, giving it that air of objectivity that he also tries to avoid.

Much better is "The Underground War In Gaza", rendered in his usual crisp black & white (the other two pieces are in color, which actually detract from their overall impact), a strip that in just four pages manages to capture the complexity of the situation where houses are being bulldozed because Israeli forces suspect they are complicit in housing contraband & terrorist tunnels. While the Israelis he interviews make a reasonable case, the bottom line is that the average Palestinian citizen repeatedly gets the short end of the stick. There is a chilling quote from an Israeli officer that wraps a ribbon around the themes of much of the book: "If I wanted to see an army without restraint, I should go to Chechnya." This quote defended the actions of his military as comparatively "gentle," essentially saying, "We may be killing some innocents and ruining lives, but at least we're not sociopathic, genocidal killers and rapists." This is obviously cold comfort and reflects an ethical code that is grossly out of whack, but is also a reflection of desperate times.

"Complacency Kills" is another slightly weak story, one that came when Sacco was embedded with a Marine unit. While that process by its nature tends to align journalists with their subjects, Sacco was well aware of that going in and wanted to examine "the tip of the imperial spear." The story gets at the tensions and camaraderie of those Marines in Iraq as they try to do their job against insurgents while trying to remain sympathetic to Iraqi citizens. It's the sort of story (minus flag-waving and easy appeals to emotion) that many have done in different formats, and Sacco acknowledges this while being grateful for the experience. "Trauma on Loan" is more interesting as a sort of journal of frustration for Sacco than as an actual piece of comics journalism; he tries to get details out of two Iraqi men who were abused for no reason by the U.S. military and who decided to sue Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. The two men, hanging out in New York and D.C. and sightseeing while trying to drum up publicity for their case, prove either too traumatized or are simply too tight-lipped to give Sacco anything beyond the basics, despite his painstaking attempts to win their trust.

Much more interesting is "Down! Up!", a story about Sacco observing a group of Iraqis training under two American officers for the Iraqi National Guard. The title is a play on words, referring to the commands of a drill sergeant who makes the trainees do push-ups after one of their many mistakes, as well as a reference to George W. Bush's stated desire for the ING to "stand up" so that "we can stand down." Sacco paints an unflattering but fair picture of the instructors as bullies and tyrants trying to instill potentially life-saving training. The trainees are not especially well-educated or in great shape, and most volunteer to get a paycheck, despite the risk to their lives from insurgents. Sacco essentially gets across the sense that no matter which side these men choose, they are doomed, and he deftly weaves himself in and out of practices and private conversations to get the big picture.

Unsurprisingly, the three longest pieces are the best, giving Sacco room to talk to a lot of people and get a number of different viewpoints. "Chechen War, Chechen Women" is a history of the shocking violence perpetrated by the Russian government and their contract soldier in Chechnya, filtered through the point of view of IDPs--Internally Displaced Persons. These are families shattered by the conflict and taken to live in embarrassing, eyesore tent cities (which the Russians were desperate to get rid of) or converted factories. This hammers home a classic Sacco theme of the powerless being at the mercy of the powerful and finding little. Thanks to 9/11, the Russian government tried to paint this conflict as fighting terrorism, and to be sure, Chechen militants only served to pour gasoline on that particular fire. As always, it's the women, children, and other innocents who suffer, not only from deprivation but from the mental anguish that results from such situations. Aesthetically, Sacco outdoes himself here, capturing the deeply wrinkled faces of the women he interviews, the detail of the squalid tents, the suffocating nature of the tiny rooms, and the bombed-out shell that is the Chechen capital of Grozny. With Sacco, it's always been about the eyes. There's a reason he never shows his own eyes and instead focuses on others--it's a technique that allows the reader to feel like they're looking the person in each panel straight in the eye. When that gaze is with a traumatized man driven to such lengths of insanity as to beat his own family because he didn't recognize them, it's especially unsettling.

Unsurprisingly, the three longest pieces are the best, giving Sacco room to talk to a lot of people and get a number of different viewpoints. "Chechen War, Chechen Women" is a history of the shocking violence perpetrated by the Russian government and their contract soldier in Chechnya, filtered through the point of view of IDPs--Internally Displaced Persons. These are families shattered by the conflict and taken to live in embarrassing, eyesore tent cities (which the Russians were desperate to get rid of) or converted factories. This hammers home a classic Sacco theme of the powerless being at the mercy of the powerful and finding little. Thanks to 9/11, the Russian government tried to paint this conflict as fighting terrorism, and to be sure, Chechen militants only served to pour gasoline on that particular fire. As always, it's the women, children, and other innocents who suffer, not only from deprivation but from the mental anguish that results from such situations. Aesthetically, Sacco outdoes himself here, capturing the deeply wrinkled faces of the women he interviews, the detail of the squalid tents, the suffocating nature of the tiny rooms, and the bombed-out shell that is the Chechen capital of Grozny. With Sacco, it's always been about the eyes. There's a reason he never shows his own eyes and instead focuses on others--it's a technique that allows the reader to feel like they're looking the person in each panel straight in the eye. When that gaze is with a traumatized man driven to such lengths of insanity as to beat his own family because he didn't recognize them, it's especially unsettling.

"The Unwanted" is Sacco's superb piece on the problems of immigration. He travels to his birthplace of Malta, the scene of an immigration laboratory on the verge of blowing up. Malta is a small island in the Mediterranean Sea that happens to be near enough to Sicily for African immigrants to sail there by mistake in overcrowded, barely seaworthy boats. Malta is ill-equipped to handle this kind of population influx, but it's also clear that cultural and racial differences spur much of the mutual antipathy between the Maltese and the immigrants. Having grown up in Miami and seen with my own eyes the horrible treatment that Haitian immigrants often receive after barely escaping with their lives from the economic and political nightmare of that country, I felt a sense of déjà vu as Sacco described the Maltese policy of detaining immigrants in substandard conditions for long periods of time.

Sacco is extremely even-handed in this piece, hearing out the concerns of the Maltese even as they expose their own racism and paranoia. The essential paradox is that they are repulsed by many of the Africans because in their eyes they act like animals, without seeing the irony in how people tend to behave in the manner in which they are treated. Many of the Africans act like criminals because they are treated like criminals from the moment they step on the island. As one more sympathetic Maltese man says, it is their duty as a people to help out those in need: "We're talking about people, not grass." Sacco crucially provides context for the migration in telling the story of one man who fled from Eritrea in Eastern Africa, knowing the government was coming to jail him (or worse), simply for speaking out. The trek he describes in getting from Eritrea to Tripoli makes tales of Mexicans sneaking across the U.S. border look like a birthday party. All that trek earns him is a chance to get in that boat, with no one to navigate it.

Most of Sacco's stories are bleak, but there's often a small kernel of hope. Things might get better for the downtrodden, war might end, tyrants might fall, freedoms might increase. This doesn't usually happen or guarantee happiness, but sometimes a new steady state emerges that doesn't always produce misery. In Sacco's last story in the book, "Kushinagar", there is no hope, in part because the steady state is so thoroughly entrenched. Sacco visits a number of small villages in the titular region of India and spends time with Musahars, the lowest of the low in India's caste system. While there is misery and squalor depicted in each of Sacco's stories, this one details actual starvation and true deprivation. The Musahars cannot find employment in an increasingly mechanized system of agriculture. They cannot usually raise crops on their tiny plots of land, especially since they have to sell that land to pay off debts to banks they had to take out to pay off loan sharks to buy food on credit. The many government subsidy programs are hopelessly corrupt, with money and supplies going to village chiefs and siphoned off for the profit of higher caste members. Some Musahars described digging around in rat holes to get the grain that they steal in order to survive.

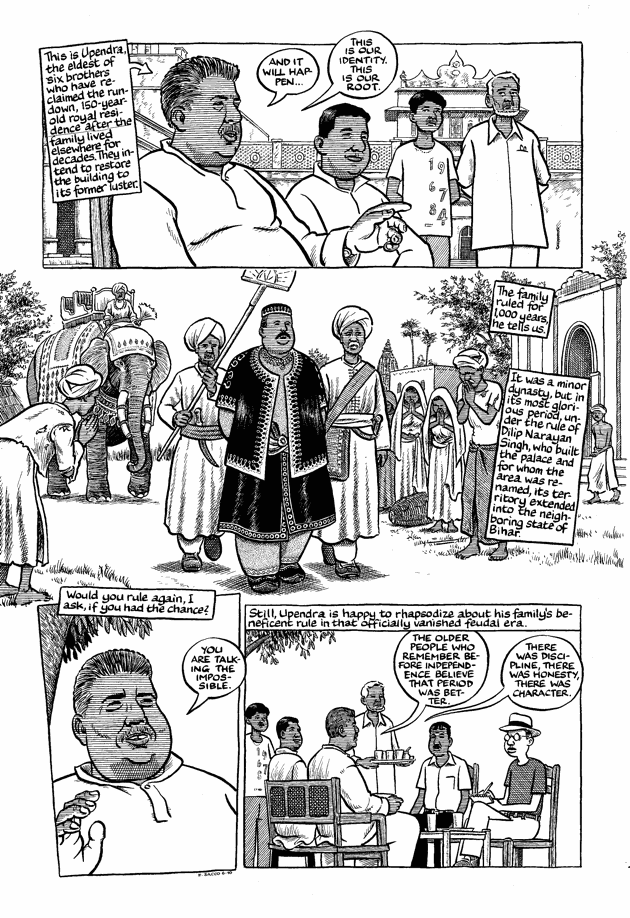

One journalist and weary advocate for the lower caste members, when asked about what will happen to the Musaharsin the future, resignedly says, "It appears obvious that all of them will be dead and they will be part of history." That's a devastating quote, but in a society that builds in such hard-wired differences and allows upper caste members to utterly ignore the law regarding lower caste members, it seems impossible to argue. The way Sacco structures the story is brilliant and serves to build up his case until we reach that one quote. He starts near the end, when the village chief and a gang of thuggish teenaged boys roust Sacco and his translator/guide out of the hut in which he is talking to the villagers. This is the end of the line, because the villagers know that any further trouble would only result in them being punished harshly by the hypocritical chief, who is obviously paranoid about them talking to a Western journalist. Sacco backs up and slowly lets the villagers talk about their conditions, the corruption they face and their total lack of a voice. Sacco then spends time with the fat-cat rajas who essentially get to treat the Musahars as slaves, when they even deign to employ them. It becomes obvious that this isn't a case of a downtrodden people ready to rise up, but rather a populace that has internalized being downtrodden as their fate.

What makes things even worse is the willing blindness of the bureaucrats Sacco speaks to, who are full of solutions for the poor while looking the other way from the corruption that siphons off funds. Sacco leaves off Journalism with a story that's more elegy than simple reportage, a mournful song for the doomed that dryly but pointedly excoriates all of those who could prevent this human tragedy but simply choose not to. It's one of his finest moments as a journalist, a case where the subjectivity of his observations on a given day bears powerful fruit.