Matthew Thurber's INFOMANIACS is my choice for best comic of 2013. Thurber is perhaps the funniest cartoonist working today, though in more of a narrative sense rather than the gag-built work of cartoonists like Michael Kupperman, Lisa Hanawalt and Sam Henderson. That said, INFOMANIACS has a looser and sillier structure than his previous book, 1-800-MICE. The latter book, originally published in comics form, had the narrative structure of a serial, with multiple and intersecting plots that were pulled together ever tighter as the story went along.

INFOMANIACS begins as a mostly improvised web comic, and its page-to-page structure reveals how Thurber tries to end each page or every couple of pages with a definitive gag and punchline. Thurber uses visual gags to some degree (simply the way he draws his characters is amusing), but he loves diving into puns, bon mots, and clever references that still manage to resonate with the story's themes. Both books use deadpan descriptions of absurd ideas rooted in science and medicine. And while INFOMANIACS has the feel of a shaggy dog story (it doesn't so much end as it just stops), it nevertheless gives a thorough airing of all the various aesthetic, cultural and political critiques that resonate throughout Thurber's work.

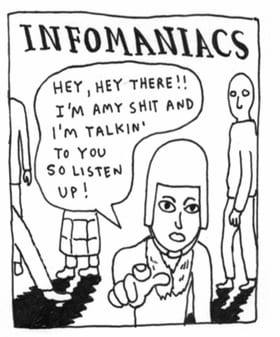

Let's unpack all of that a bit. Thurber begins INFOMANIACS in media res, introducing the reader to protagonist Amy Shit, the subway-dwelling eco-rapper who brings us into one of the nominal plotlines: an "internet serial killer" on the loose. Each of these first few pages introduces a major character in a loose manner, as the second page introduces parallel protagonist Ralph (a student), and connecting figure Dr. Albert Radar (Ralph's therapist and Amy's bandmate). I'm not sure if Thurber used a different kind of tool to draw the first six or seven pages of the book, but the quality of his drawing is entirely different than the rest. His panels are more cramped, his figures are smaller, and his line is wobblier. There is spontaneity in these pages, to be sure, but it feels dashed-off, as though Thurber was throwing ideas at the wall to see if anything would stick.

Those characters, the image of a knife-like cursor coming out of a screen and the concept of the Man Who Has Never Seen The Internet must have stewed in Thurber's mind for some time, because according to the artist's date on each strip, there was a five-month delay between the last rough page and the first section that actually has jokes in addition to odd concepts. Indeed, the concept of the SmartPencil (with a sales patter that would make Apple blush, including bits like "pinktip (TM) eraser-mouse") is the first minor salvo in Thurber's book-looking strafing of the internet and internet culture. The art from here on art is Thurber's more typical style, mixing a clear, thin line with dense cross-hatching. The way he flips between the two creates an environment that at times feels desolate and lonely (the minimalist style) and cramped and claustrophobic (the dense style).

Those characters, the image of a knife-like cursor coming out of a screen and the concept of the Man Who Has Never Seen The Internet must have stewed in Thurber's mind for some time, because according to the artist's date on each strip, there was a five-month delay between the last rough page and the first section that actually has jokes in addition to odd concepts. Indeed, the concept of the SmartPencil (with a sales patter that would make Apple blush, including bits like "pinktip (TM) eraser-mouse") is the first minor salvo in Thurber's book-looking strafing of the internet and internet culture. The art from here on art is Thurber's more typical style, mixing a clear, thin line with dense cross-hatching. The way he flips between the two creates an environment that at times feels desolate and lonely (the minimalist style) and cramped and claustrophobic (the dense style).

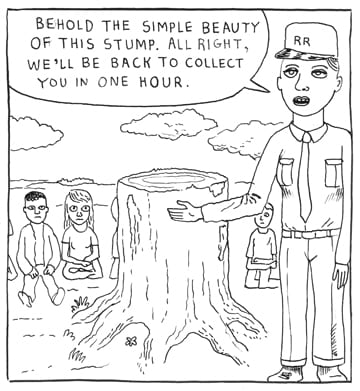

Poor Ralph is addicted to the internet and is unable to remember how to open up a door without googling it first. Radar then has Ralph sent off to Reality Rehab, a work camp for those addicted to the internet. This entire sequence is just one example of Thurber coming up with an idea and riffing on it for a few pages. The parody of rehab culture is hilarious, especially the complicated "guerrilla internet" that the campers use, complete with human "search bars", "browsers", "results runners", etc. Later, Ralph discovers the "Download Club", which substitutes conventional porn for watching bacteria reproduce (including, of course, a "money shot"). During the course of the book, Thurber seems to be working to entertain himself above all else. When he gets tired of an idea, he either switches to another character or simply writes the idea out of the book. Reality Rehab could make up an entire book, but Thurber moved on when he wanted to explore other ideas.

Poor Ralph is addicted to the internet and is unable to remember how to open up a door without googling it first. Radar then has Ralph sent off to Reality Rehab, a work camp for those addicted to the internet. This entire sequence is just one example of Thurber coming up with an idea and riffing on it for a few pages. The parody of rehab culture is hilarious, especially the complicated "guerrilla internet" that the campers use, complete with human "search bars", "browsers", "results runners", etc. Later, Ralph discovers the "Download Club", which substitutes conventional porn for watching bacteria reproduce (including, of course, a "money shot"). During the course of the book, Thurber seems to be working to entertain himself above all else. When he gets tired of an idea, he either switches to another character or simply writes the idea out of the book. Reality Rehab could make up an entire book, but Thurber moved on when he wanted to explore other ideas.

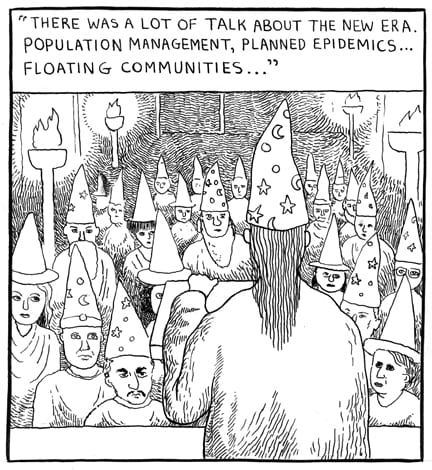

In particular, he seemed eager to explore familiar ground in a different manner. Common Thurber themes include critiques of global capitalism, the corporation as a variation on a religious cult and/or conspiracy, the ways in which culture is debased to merely viewing spectacle, and how ecological concerns inform our everyday life. Of course, he addresses these issues in over-the-top and frequently loopy ways. Entrepreneur and CEO Victor Valkyrie (the villain of the piece), controls both culture and the economy by running a successful social platform called Entirenet. It's essentially the worst nightmares regarding the loss of net neutrality in one crazed package, as he and his followers (the Merlin League, where they must all dress up as wizards and wear beards) eat cupcakes that are supposedly made from the brain of the only man who hadn't seen the internet. This is also an example of Thurber finding ways to connect characters and concepts introduced early in the book; these sorts of callbacks have a long-form improv quality to them, and they are continued throughout the book.

In particular, he seemed eager to explore familiar ground in a different manner. Common Thurber themes include critiques of global capitalism, the corporation as a variation on a religious cult and/or conspiracy, the ways in which culture is debased to merely viewing spectacle, and how ecological concerns inform our everyday life. Of course, he addresses these issues in over-the-top and frequently loopy ways. Entrepreneur and CEO Victor Valkyrie (the villain of the piece), controls both culture and the economy by running a successful social platform called Entirenet. It's essentially the worst nightmares regarding the loss of net neutrality in one crazed package, as he and his followers (the Merlin League, where they must all dress up as wizards and wear beards) eat cupcakes that are supposedly made from the brain of the only man who hadn't seen the internet. This is also an example of Thurber finding ways to connect characters and concepts introduced early in the book; these sorts of callbacks have a long-form improv quality to them, and they are continued throughout the book.

Regarding ecology, Thurber addresses these issues in a typically playful manner, by showing us a recording session with Amy Shit and her back-up rappers, the Climate Game-Changers. Their song is called "Global Chillin'". In a two-page sequence, each member of the band (including anthropomorphic members like Mousey B Junior, God Snake, Cat Lady and Tuxedo Laughing Gas) gets a verse in. Therapist Dr. Radar talks about "This new talking cure which they call it freestyling", which is yet another clever throwaway line. Amy's rough and tumble punk, eco-activist persona is as tidy a package of a character as Victor Valkyrie is, only with all of his values reversed. Thurber treats both of them playfully and with a touch of the absurd, which steers him clear of didacticism.

Regarding ecology, Thurber addresses these issues in a typically playful manner, by showing us a recording session with Amy Shit and her back-up rappers, the Climate Game-Changers. Their song is called "Global Chillin'". In a two-page sequence, each member of the band (including anthropomorphic members like Mousey B Junior, God Snake, Cat Lady and Tuxedo Laughing Gas) gets a verse in. Therapist Dr. Radar talks about "This new talking cure which they call it freestyling", which is yet another clever throwaway line. Amy's rough and tumble punk, eco-activist persona is as tidy a package of a character as Victor Valkyrie is, only with all of his values reversed. Thurber treats both of them playfully and with a touch of the absurd, which steers him clear of didacticism.

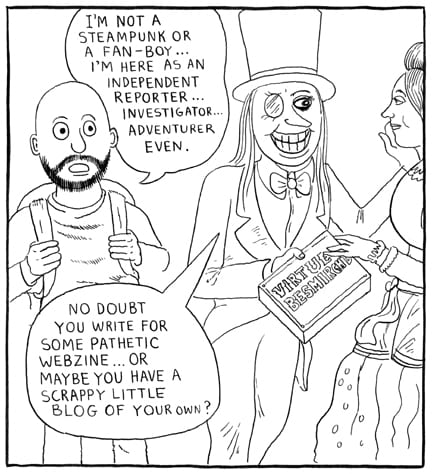

All of this action occurs within the first forty or so pages of the book. From there, Thurber creates different kinds of spectacles for Ralph, as he's first busted out of Reality Rehab, goes to an organic server farm featuring the edible internet, and then eludes the authorities by joining the CIA and its "micro-agency", the ATF: the Anthropomorphic Task Force. Longtime Thurber fixture and anthropomorphic horse Mr. Colostomy is one of those agents, who sends Ralph on a mission to spy on Valkyrie. Despite his wealth Valkyrie isn't very happy, having to deal with his son's steampunk obsession and agents who demand that he listen to their dubstep albums as a form of payment. Thurber almost turns him into a sympathetic character, despite the vicious lampooning of his libertarian politics.

All of this action occurs within the first forty or so pages of the book. From there, Thurber creates different kinds of spectacles for Ralph, as he's first busted out of Reality Rehab, goes to an organic server farm featuring the edible internet, and then eludes the authorities by joining the CIA and its "micro-agency", the ATF: the Anthropomorphic Task Force. Longtime Thurber fixture and anthropomorphic horse Mr. Colostomy is one of those agents, who sends Ralph on a mission to spy on Valkyrie. Despite his wealth Valkyrie isn't very happy, having to deal with his son's steampunk obsession and agents who demand that he listen to their dubstep albums as a form of payment. Thurber almost turns him into a sympathetic character, despite the vicious lampooning of his libertarian politics.

What's surprising about the book is that despite all of the unrelenting silliness on page after page, the plot actually starts to tighten up and the relationships between characters become clearer. While doing that, Thurber continues to throw in new characters and concepts, like the talking worm who lives in Dr Radar's hat, Amy's brother Ned who smashes technology, a San Diego Comic-Con that lasts a month and takes place on a mountain, etc. There are more throwaway gags, like an airline whose planes never crash because they are held aloft by the sky god every passenger must worship or steampunk accessories like mints that make one's breath smell like tuberculosis "without the annoying fatal qualities." The relationship between Amy and Ralph is revealed in the book's climax, and while it doesn't make complete sense to even the characters in the book, the ways in which one character's adventures affect the other's is clever, especially in retrospect. Thurber suggests that culture and identity is all a matter of role playing, and that the real struggle is finding a way to determine one's own role.

What's surprising about the book is that despite all of the unrelenting silliness on page after page, the plot actually starts to tighten up and the relationships between characters become clearer. While doing that, Thurber continues to throw in new characters and concepts, like the talking worm who lives in Dr Radar's hat, Amy's brother Ned who smashes technology, a San Diego Comic-Con that lasts a month and takes place on a mountain, etc. There are more throwaway gags, like an airline whose planes never crash because they are held aloft by the sky god every passenger must worship or steampunk accessories like mints that make one's breath smell like tuberculosis "without the annoying fatal qualities." The relationship between Amy and Ralph is revealed in the book's climax, and while it doesn't make complete sense to even the characters in the book, the ways in which one character's adventures affect the other's is clever, especially in retrospect. Thurber suggests that culture and identity is all a matter of role playing, and that the real struggle is finding a way to determine one's own role.

Like in 1-800-MICE, Thurber seems disinterested in a pat denouement, preferring to end each book suddenly. The former book concludes with an explosion and a couple of characters floating away. Similarly, INFOMANIACS concludes with an explosion and a deft finish with a plot device. The last page features a couple of characters once again floating away in a balloon, giving it an almost non sequitur happy ending. The way Thurber structures the book is perhaps its greatest strength, as there's a kind of narrative nimbleness that switches scenes or introduces new ideas a beat ahead of the reader getting tired of the old one. There's a balance of dada culture-jamming absurdity, rock-solid gags (a file downloaded from the internet becomes a file used to cut through prison bars) and fluid action sequences that give the book a sense of urgency and forward movement. It's not as striking and original an achievement as the more intricate and narratively dense 1-800-MICE, but INFOMANIACS succeeds by playing to Thurber's strengths as a humorist without sacrificing the complexity of his thematic interests.

Like in 1-800-MICE, Thurber seems disinterested in a pat denouement, preferring to end each book suddenly. The former book concludes with an explosion and a couple of characters floating away. Similarly, INFOMANIACS concludes with an explosion and a deft finish with a plot device. The last page features a couple of characters once again floating away in a balloon, giving it an almost non sequitur happy ending. The way Thurber structures the book is perhaps its greatest strength, as there's a kind of narrative nimbleness that switches scenes or introduces new ideas a beat ahead of the reader getting tired of the old one. There's a balance of dada culture-jamming absurdity, rock-solid gags (a file downloaded from the internet becomes a file used to cut through prison bars) and fluid action sequences that give the book a sense of urgency and forward movement. It's not as striking and original an achievement as the more intricate and narratively dense 1-800-MICE, but INFOMANIACS succeeds by playing to Thurber's strengths as a humorist without sacrificing the complexity of his thematic interests.