The death toll is high and the racial slurs fly in Infidel, Pornsak Pichetshote and Aaron Campbell’s horror series about a murderous presence that seems to feed on hatred. But to paraphrase one of Infidel’s characters, in a room full of shadows, writer Pichetshote is obsessed with the light. While a literal specter of bigotry hangs over much of the book, claiming the lives of many members of Infidel’s multicultural cast, Pichetshote writes with a deep empathy that’s likely to cause readers to repeatedly reassess their basic assumptions about his characters. Infidel’s content is often shocking, but Pichetshote writes an intensely humanist horror story with a light at the end of its tunnel.

Infidel’s plot revolves around two lifelong friends and women of color, Aisha and Medina, who both live in an apartment building where a mysterious bomb blast recently killed several people. Both grew up in the Muslim faith, but have taken different paths in adult life. Aisha still dons a hijab, takes comfort in prayer, and makes excuses for the casually racist opinions espoused by Leslie, her boyfriend Tom’s mother. Medina is more overtly radical. “Racism’s a cancer that doesn’t get cured,” she tells Aisha. “The best you get is remission.”

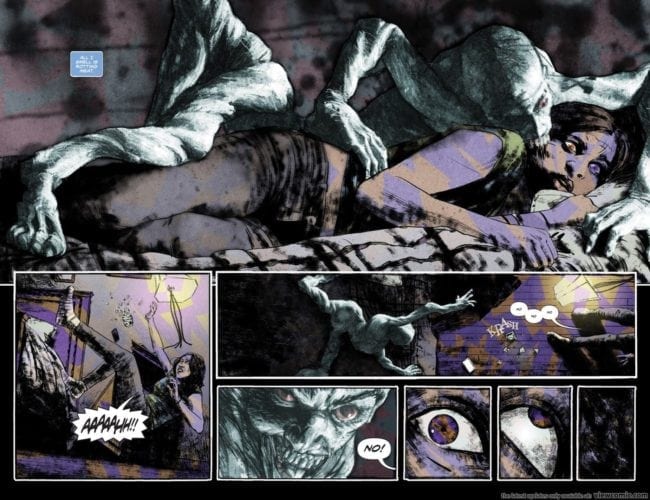

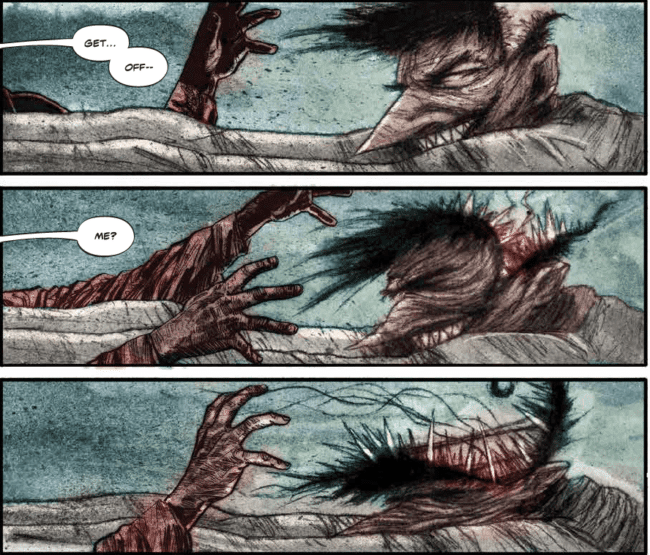

Aisha and Medina’s lives are upended when the aforementioned spirit begins intervening first in Aisha’s life and then in the lives of other residents of their building. The presence takes the guise of freakishly deformed creatures who spout racial epithets and causes those it appears to to commit violent acts. As the spirit continues to wreak havoc, our protagonists set out to determine how it came to be and how to vanquish it.

Infidel marks a surprisingly delayed comics-writing debut for Pichetshote, best known for editing critically acclaimed mid-2000s Vertigo titles like We3, Seaguy, and Sweet Tooth. One might expect Infidel to be a highly personal book for him, and clearly the concepts of racism and cultural (mis)understanding are close to his heart. But in many ways Infidel is a very selfless work. Pichetshote, who is Asian-American, has noted in interviews that he did extensive research to accurately portray the varying intersections of racial, religious, and gender identities represented in Infidel’s cast of characters.

His legwork pays off. Aisha, Medina, and multiple other characters in the book feel lived-in, genuine, and very complex. Pichetshote likes to keep his audience guessing by challenging any preconceived notions readers may jump to, even about characters whose identities are less marginalized than, say, Aisha’s. (For example: if you think the casually racist old white lady is going to be the main antagonist, Pichetshote nips that one in the bud surprisingly quickly.)

His legwork pays off. Aisha, Medina, and multiple other characters in the book feel lived-in, genuine, and very complex. Pichetshote likes to keep his audience guessing by challenging any preconceived notions readers may jump to, even about characters whose identities are less marginalized than, say, Aisha’s. (For example: if you think the casually racist old white lady is going to be the main antagonist, Pichetshote nips that one in the bud surprisingly quickly.)

Campbell brings the story to visual life with a well-pitched blend of astute minimalist realism and truly unsettling horror. He echoes artists like Michael Gaydos and Michael Lark in his ability to render highly expressive and distinct characters through economical line work and effective use of black. Appropriately, his portrayal of the sinister presence that stalks the characters seems to come from a different artistic world entirely. The sickly and twisted spirit, rendered in a painterly style by colorist and editor Jose Villarubia, recalls the disturbingly brilliant apparitions summoned by artists like Dave McKean and Bill Sienkiewicz. Campbell is an ideal creator both to sell you on Pichetshote’s characters as very real, believable people, but to also drive home Infidel’s many visceral moments in truly memorable fashion.

Villarubia’s coloring work is excellent, working from a gritty palette with pops of bright color in low-key conversation scenes and then breaking out into garish riots of color in the hallucinatory sequences. Jeff Powell’s lettering work is also effective, particularly in the nightmarish scrawls of racist babble that stagger across the page whenever the spirit appears.

Infidel’s only real flaw is that certain characters introduced later in the story pale in comparison to the much strongr character-building Pichetshote has done in the early going. Aisha is sidelined about one-third of the way through the book, and a flurry of what seemed to be mere supporting characters get promoted to major players for the story’s middle stretch. But compared to Aisha, Medina, Tom, and Leslie, we know little about these characters. The extended cast includes even more unique cultural identities that might be mined for further insights or interesting character work, but some of them feel more like generic plot movers than fully realized characters.

Infidel’s only real flaw is that certain characters introduced later in the story pale in comparison to the much strongr character-building Pichetshote has done in the early going. Aisha is sidelined about one-third of the way through the book, and a flurry of what seemed to be mere supporting characters get promoted to major players for the story’s middle stretch. But compared to Aisha, Medina, Tom, and Leslie, we know little about these characters. The extended cast includes even more unique cultural identities that might be mined for further insights or interesting character work, but some of them feel more like generic plot movers than fully realized characters.

The horror genre is at its most potent when it attempts to advance understanding of our humanity or to empower its audience to confront its own fears. Infidel does both, encouraging readers to think twice before jumping to conclusions about its characters and pushing us to confront the biggest fear in today’s society: fear of the other, the fear of the humanity we rush to deny in those we don’t fully understand. Infidel will disturb you, but it’s may also send you out with a newfound sense of faith in humanity.