Originally serialized in 1997 by Shukan Josei, a weekly news magazine for adult women, Moyoco Anno’s In Clothes Called Fat is broken into 14 chapters and an epilogue that track a few years in the life of Noko Hanazawa. Noko is introduced as a compulsive over-eater with a thankless office job and an unappreciative boyfriend of nine years named Saito. Noko finds relief from the pain of the endless hate spewed at her by her coworkers due to her size in Saito, despite his refusal to progress their relationship outside of a few routine visits within the walls of her apartment. Noko’s colleagues revile her as her appearance leads them to believe she is sloppy, and she is frequently cast as the office scapegoat whenever a mistake turns up in the work. Noko turns to repeatedly consuming huge portions of food to quash her anxieties about her status, which causes a rapid weight gain she notes feels like “wearing a leotard of flesh that can never be removed.” This hint at body horror recalls the seminal manga Helter Skelter by Anno’s mentor Kyoko Okazaki, which began serialization in 1995, and which also followed its protagonist on a downward spiral of body dissociation and mutation.

In the world of In Clothes Called Fat, also as in Helter Skelter, a beautiful appearance isn’t just something to strive for; it determines your lot in life. Enter Mayumi, the office sweetheart, who threatens Noko’s already precarious sanity. Beloved in the office despite her questionable work ethic, Mayumi is always flocked by her admiring colleagues and outside of the office men constantly pester her. Her hair is perfect and her underwear is La Perla. Mayumi makes little secret with the rest of the office ladies about her affair with Saito; Noko overhears Mayumi recount their sexual escapades (“vanilla”) while hiding in a bathroom stall eating a candy bar. In this scene, the difference between Noko and her female colleagues is severe in Anno’s hands: while her “normal” (thin, pretty) coworkers are drawn as Anno’s signature wide-eyed waifs, Noko is both inflated and flattened at once, as abstracted as the Michelin man. Here, Noko’s appearance is not just a disruption in her office life, but also a formal disruption of Anno’s josei fashion-plate aesthetic.

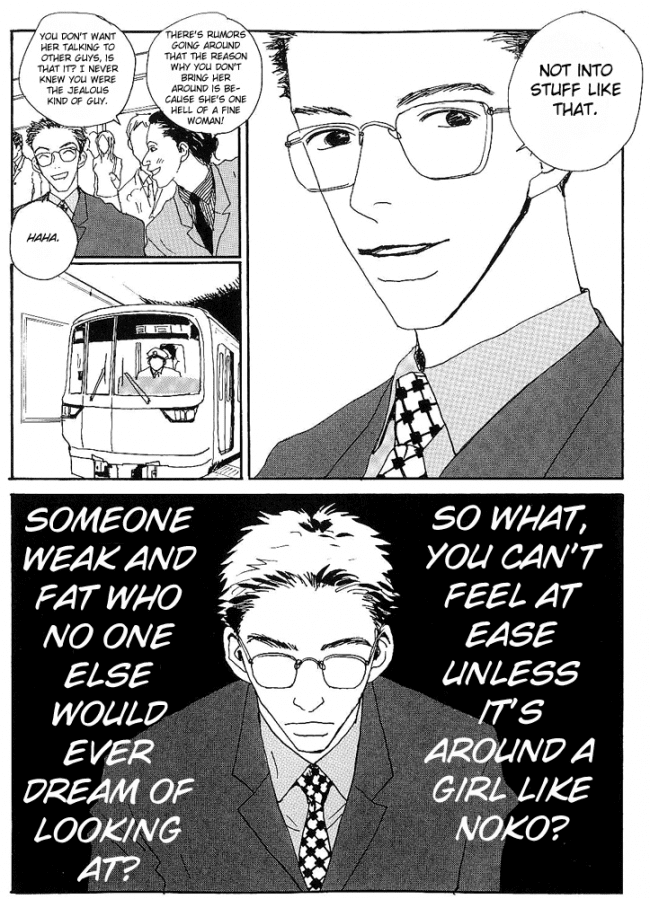

Flesh acts as both commodity and canvas in In Clothes Called Fat. While her boyfriend continues to stray, Noko calls a dating service (“One thing I should warn you about,” Noko explains on the phone, “I am very fat.”). She arranges a rendezvous with an elderly man in a hotel, who pores over her body while explaining his connoisseurship of superfluous flesh. He discourages Noko’s expressed wish to become thin and pretty as her true desirability is in her silky skin and warm body. After the encounter turns sexual he leaves her with an envelope full of cash and a note thanking her “for the meat.” Noko uses the cash on an expensive health spa center that promises weight loss. However, she is unable to stop herself from her compulsive overeating, and she learns to control the effects of her compulsion by vomiting. As Noko quickly develops into a bulimic, Mayumi degrades Saito for taking advantage of Noko’s insecurities, which in turn showcases his own insecurities and failings as a man. In her own exploitation of flesh, Mayumi dominates Saito and burns him with cigarettes, deliberately leaving the burn marks for Noko to find.

Mayumi acts as enforcer throughout the story: Mayumi punishes Saito for his lack of masculinity, as he still lives with his mother and enables Noko’s addiction to maintain his cradled domestic life. Mayumi punishes Noko for her appearance and her willingness to be treated as a doormat. Little insight is provided for Mayumi’s behavior, only her expressed need to always keep human footstools in order to maintain her superiority. This denial of dimension is one of the few unfortunate lacking elements in In Clothes Called Fat; while a pop psychology understanding of Mayumi might hinder her thorough performance in an archetypal “pretty bitch” role, it would provide a greater understanding of the ways women internalize and handle the domineering male gaze in the world of Clothes. Does Mayumi suffer for her desirability in ways parallel to the ways Noko suffers for her undesirability? Does she have an awareness of a world outside of body image and self control, and if so, is she aware she is absent from it? Is there even potential for that world to exist in In Clothes Called Fat?

The fascinating difference between Clothes and Okazaki’s Helter Skelter is that while the story of Helter follows a model whose profession demanded the physical perfection of an ideal, the occupations of the characters in Clothes are much more ordinary. This is, of course, where the dark comedy of Clothes comes to light. It is important to note that Anno holds back on cheap punches at Noko’s weight and eating issues, instead making room for the acerbic irony of how the world treats her disorder: for example Saito’s disgust with Noko’s now prized, hard-won slender body results in his attempt to violently force-feed her; or Noko’s elderly lover describing the folds of her labia as “silken mochi cakes” while admiring her body and once finished with her calling her flesh “meat.” One thing is clear in both works: final judgment of just how perfect perfect is always rests with the subjective eye of the male gaze.

Eventually, with the love triangle disseminated, the story ends with the potential for Noko to assume a new role as a Mayumi-type enforcer once she spots Saito with a new, heavier girlfriend. However, in that moment her physical weakness due to her months of self-abuse lays Noko out, and she soon returns to her compulsive overeating. This denial of introspection and ascension to myth (as with Liliko’s ultimate transformation in Helter Skelter) is the deepest and darkest irony of the work. True to the outlook of an eating disorder sufferer, little exists outside of the addiction. However, moreso than a clinical approach to explaining the vicious cycle of binging and purging, Anno gives us an unflinching look at a society not just obsessed with appearance, but ultimately with denying women the physical space and agency they are entitled to.

When Noko acts out in violence she is not necessarily just seeking revenge or numbing her anxieties—for example, when she trashes the ladies locker room in secret, slaps Mayumi in front of her coworkers, or orders all of the courses off a menu only to noisily vomit them up and come back for more to an audience of a shocked wait staff—she is asserting her existence and right to act and occupy space as much as anyone else. This is her defiance in the face of a society that demands she limit her desires to keeping herself desirable; these are ultimately also the most satisfying scenes in the book. Size determines the ways in which women are perceived to the extreme: because Noko occupies too much space she must be sloppy, she must be the cause of mistakes at work, without question. Because Mayumi is slender she is controlled and reasonable, therefore her offenses must be small as well.

One hopes Noko can find a way to use her anger to a more positive outcome in the beginnings of the second chance we leave her with, but as Anno asserts in Clothes, before this can happen the right to space and agency has to be on the menu.