Prior to reviewing Teva Harrison's cancer memoir, In-Between Days, I want to provide a bit of context. Both of my parents died from cancer. I have worked in a cancer center for the last 28 years, not usually directly with patients, but quite often. So I tend to hate cancer narratives that use words like "heroic" or otherwise apply exceptional qualities to those who are afflicted with the disease. Cancer does nothing to elevate the character of someone who suffers from it; in fact, what it tends to do is reveal character in a dramatic way. Interestingly, those who suffer from the worst kinds of cancer (metastatic, inoperable, etc) tend to be the most understanding, kind, and introspective patients. Those with the easiest-to-treat kinds of cancer tend to be the most melodramatic and demanding.

The three best memoirs I've read about cancer are the rawest and most honest emotionally, revealing the ways in which cancer turns the lives of the patients and their loved ones upside down. Harvey Pekar, Joyce Brabner, and Frank Stack's Our Cancer Year is fantastic, as it offers a quotidian, painful look at how cancer and chemotherapy can cause horrible side effects and affect mental status. Miriam Engleberg's Cancer Has Made Me a Shallower Person is hilarious in the face of her ultimately fatal disease. Sharon Lintz's cancer stories in her Pornhounds comic were also unsparing, sharply observed, and funny. Harrison's book isn't as good as any of those comics for a variety of reasons, but it's still bracing, powerful, and achingly honest.

Just in her thirties, Harrison was initially diagnosed with Stage III breast carcinoma, but a subsequent bone scan revealed distant metastases. This is disease outside of the original primary site, indicating widespread disease. This is where treatment intent goes from curative to palliative. How much time the patient has left depends on a wide range of factors. The book is formatted so that a single page of Harrison's comics on a subject is followed by a subsequent bit of text that fleshes it out. The comics are much more immediate and raw than the obviously closely considered text, but for the most part they achieve a nice synergy, as Harrison clarifies and expands upon the subjects she brings up in the comics.

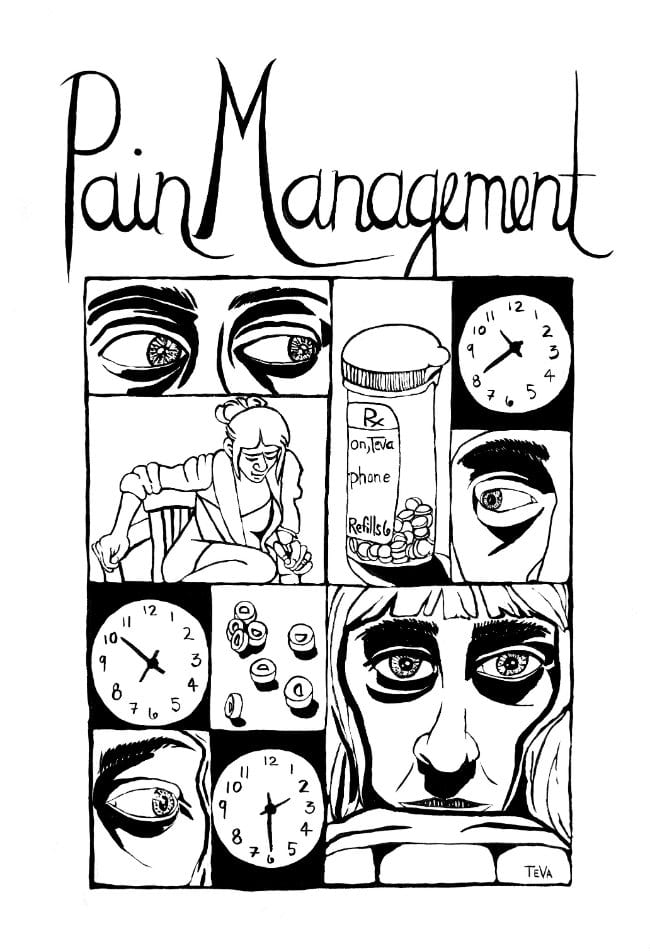

The results are a heartfelt expression of someone who knows they have a fatal disease, but not how much time they have left. In Harrison's case, there's also the highly mixed feelings regarding her appearance and functionality. The initial round of radiation she got brought incredible relief for her bone pain, and she took advantage of that as best she could: running, being active, enjoying life. Having lost little hair and looking slim brought her compliments, which made her feel awkward and even guilty. On the other hand, there were days of totally incapacitating pain that she had to deal with, pain that would send her in a narcotic haze to barely hang on. There's a sense of frustration of losing her mental acuity when on her opioids, but that's matched by the pain she has to endure when she's not on them. Harrison rejects the narrative of cancer as an enemy with a personality, which reflects the idea of an intentionality to cancer that we can resist. Instead, it's just a thing that happens, and she had the bad luck to experience it.

At the same time, that realization leads her to a sense of profound gratitude. There's even a sense of gratitude regarding the effects of both cancer and therapy and how it hasn't affected her quality of life as much as it does others. That sense of mindfulness and temporality is something she has to double down on as an atheist, especially since no one else in her support group was an atheist. After a strong opening chapter focusing on the disease and her adjustments to it, the book wobbles a bit when it focuses solely on her husband and family. It's not that this section isn't touching, but that she loses narrative sharpness in this section. It doesn't have the same pace or touch, and the narrative drags compared to the rest of the book. Things pick up again when she talks about how society treats her and how she is supposed to respond, as well as the short final chapters where she expresses hopes, fears, and dreams.

The comics themselves remind me a little of the poetic, almost clipped affect of Jenny Zervakis. There's not much in the way of sentimentality here, especially as she thinks about what bad things she might have done to cause her to get cancer, before she dismisses such thinking. Her line is thick and almost muscular, a kind of crude and immediate naturalism. That line fits in well with her blunt and frank discussions about things like the sexual problems that came about as a result of having her ovaries and Fallopian tubes removed and the early menopause that resulted. The immediacy of her line also reflects the way in which her comics are in many ways a howl against her mortality, the bad hand she was dealt, and the bizarre and awful ways her life transformed so quickly and irrevocably.