Some works fall to ruin over time, and some are ruins on arrival. Kristen Radtke’s Imagine Wanting Only This is the former, the product of shaky construction. One part graphic memoir, one part visual essay, Imagine considers the impermanence of things, with a focus on human mortality and the structures we create. It is a taxing place to visit.

Imagine Wanting Only This follows Radtke’s narrator/avatar across several years and locations, placing Radtke first at a site of an early-twenties cohabitation and then at graduate school and afterward. As the years advance, her narrator’s curiosity about declining cities and structures grows into true fascination, leading to an ambitious, international survey of ruins during her time in grad school. The circumstances surrounding this project are severe: the passing of an uncle, the passing of a friend, and the possibility of a hereditary heart condition. To critique the resulting work is not to suggest that these events deserve anything less than real empathy. But the memoir blurs exploration and consumption in a manner that may make some readers queasy, and the visual choices on display undermine the effectiveness of the book.

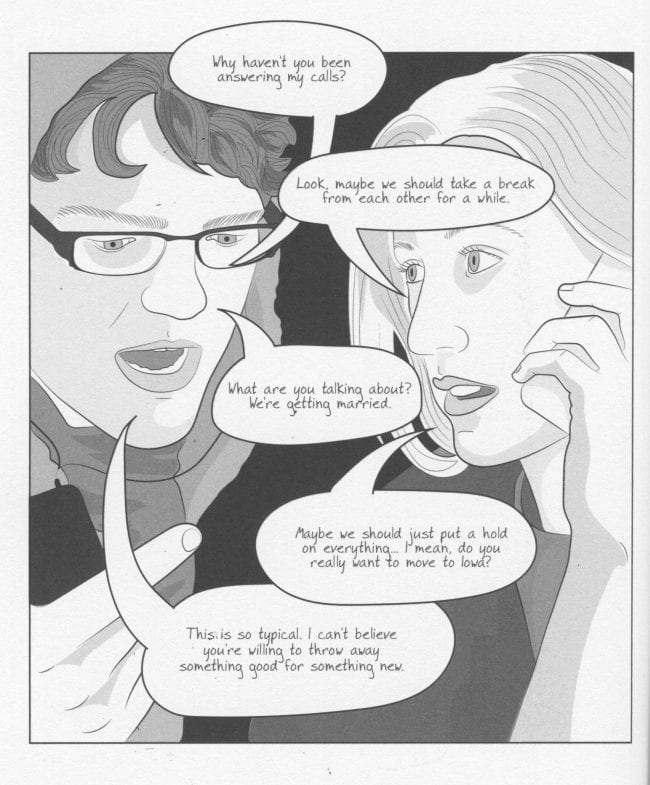

Scenes with the potential to intensify Imagine’s themes of decline and decay—a wake, a breakup call—are often blunt in their execution or awkwardly staged. Radtke’s grayscale, photo-referenced artwork registers as not drawn but traced, with static sequences across panels and unnaturally smooth figures within panels. The approach to light and shadow gives most objects, including people, a plastic sheen; the placement of certain captions and speech balloons appears to be a last-minute consideration.

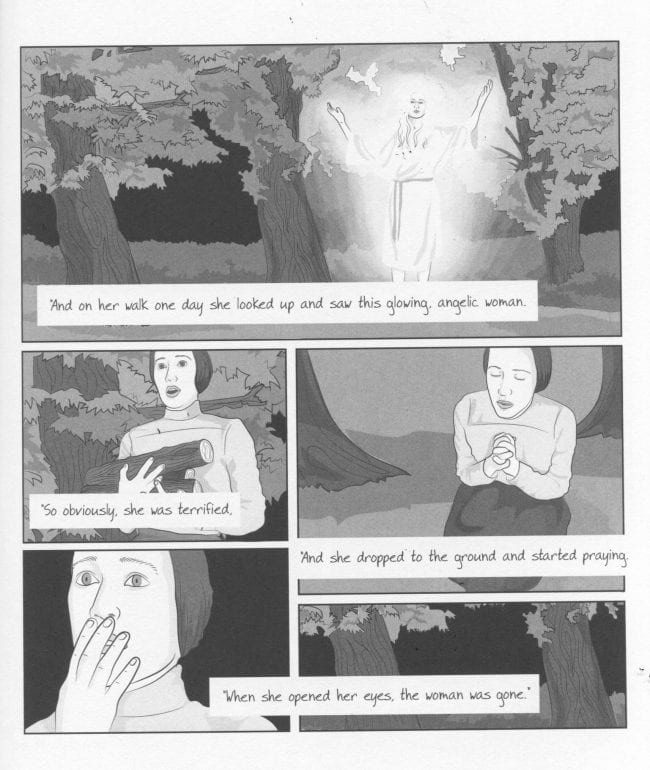

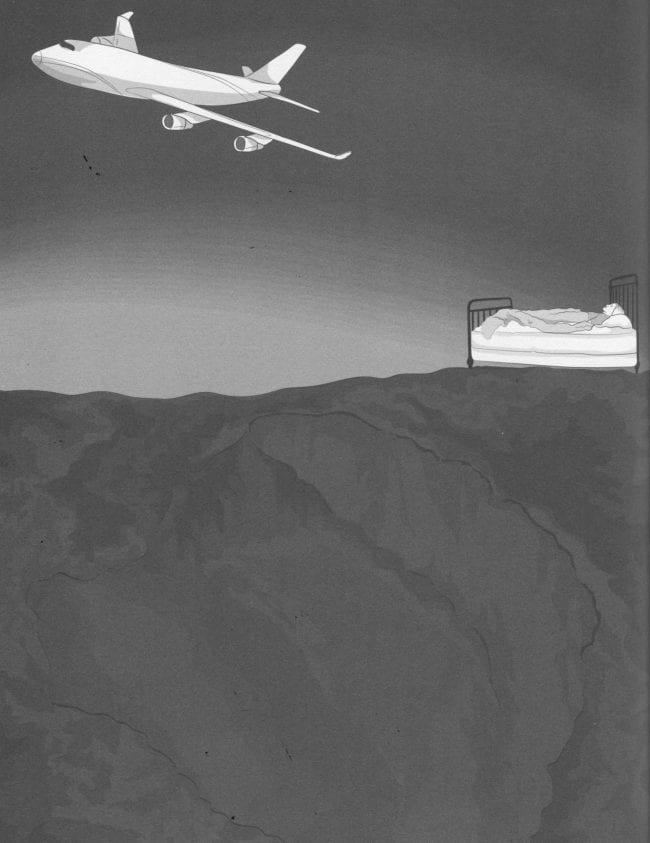

While some pages fall flat, a few tip into the ridiculous. One sequence, about late-night travel anxieties, concludes with comedic literal-mindedness. Another has Radtke’s mother describing a legend in which the Virgin Mary appears before one of their ancestors, with the memoir visualizing the event. Afterward, Radtke does not appear convinced, but a reader may struggle to discern just how absurd Radtke finds the story—the pages would make for a goofy display even if all parties were true believers. Later, Radtke’s narrator visits a museum devoted to mining, and one page juxtaposes a museum display’s miniature figures against the craggy hands and face of a “real” miner. There’s something to this contrast—about how dangerous work can be sentimentalized, or about the erasure of the dangers working people have to endure—but it’s muted by these figures all appearing to inhabit the same sort of uncanny valley.

As an essay, the book invites concerns well beyond any comics-formalist complaints. The idea of ownership enters Imagine Wanting Only This early. Describing a crowded post-college living situation in “a crumbling neighborhood on Chicago’s west side,” Radtke’s narrator says, “the place felt like ours. The fact of the house’s missing facade and its boarded front windows seemed of little concern.” The aesthetics of the place get a mention; the complexities of gentrification do not. Later, as Radtke’s narrator begins grad school in Iowa City, a caption notes, “It was an easy place to feel you’d conquered. It was a whole new kind of ownership.” Although these pages come early in the book’s chronology, the sentiment lingers as the memoir’s scope expands. Soon Radtke’s narrator begins documenting visits to various world ruins. The book presents “[t]he remnants of America in Vietnam,” “the killing fields of Cambodia,” and other location in list form, an image or two for each, photo referenced as if to annex the sites’ gravitas.

If Radtke’s narrator in Imagine Wanting Only This projects outsized feelings of ownership, that itself is not a failing of the book. With a line like, “[i]t felt like I had to see everything, as if it was the only way my life would count or matter,” Radtke’s narrator acknowledges her pursuit of ruins is more a matter of urge than of altruism, and as the substance of a literary work, that’s not a bad thing either. The willingness to be unflattering to oneself should probably be a prerequisite for memoirists. What’s frustrating about this memoir, and perhaps the best measure of it, is what the book does and doesn’t do in regard to its writ-large gentrifier’s mentality. Imagine is not, for instance, a performance of privilege that eventually challenges readers to examine their own entitlement—that would be a very generous reading of the work, anyway. Until the end, the book is more concerned with the success or failure of this existential grasping than the impulses behind it.

When Imagine Wanting Only This reaches the subject of Detroit, Radtke’s narrator offers a defense of the artists and the journalists who have already been documenting the city’s hardships, one a reader might also take as a preemptive defense of Imagine: “Perhaps critics call images of Detroit ‘perverse’ because they mirror a life we recognize … We forget that everything will become no longer ours.” These lines are spiky, provocative, and insightful, and yet they confine Detroit to a dialogue among onlookers. Meanwhile, the city still has a population in the hundreds of thousands, and there’s not a line here from any living resident. This is the book at its best and its worst: it urges readers to view spaces differently but operates with its own set of blinders.

Near the memoir’s end, during the same trip on which Radtke’s narrator visits the mining museum, the book does give voice to people who inhabit one of the United States’ changing, challenged landscapes. These scenes are troubling in their own way. After discussing the fate of Gilman, a Colorado mining community, with Lois, a former resident, Radtke’s narrator says,

I didn't like the things I'd heard from Lois. I'd wanted the story of Gilman to have more immutability somehow, but she spoke of it all so casually. … I wanted her to say that they'd lost something irreclaimable, as if it'd show me that maybe someday I could claim anything with this much ferocity.

To conduct this interview, Radtke’s narrator travels to Colorado Springs, which the book refers to as “a worn-down industrial town.” Perhaps, in part, it is; it’s also the site of ten different colleges, and two-thirds as populous as Denver. The selective framing of this language suggests that even if these encounters in Colorado didn’t meet Radtke’s expectations, the book is not above picking the facts that suit it best.

The memoir’s last, best burst of self-awareness comes near the end of this Colorado section: “I assign meaning to these scooped-out places as if obsession equals authority. But there's nothing to understand except that I have no business understanding what I cannot feel.” Radtke’s narrator soon follows this with, “to know what [the people of these places] were, I'd thought, meant I'd given them something. Something like permanence”—a thought that reduces Radtke’s subjects to needy abstractions, even as the project acknowledges its own limitations. Imagine Wanting Only This carries this ambivalence toward the end, a sense of nothing truly attained, concluding with words of vague lyricism and bad renderings of what New York City might look like underwater. New York too could be a ruin, Imagine says. If that happens, toss this book into the flood.