Reading I Will Bite You makes me think that Joseph Lambert's best work is ahead of him. It's obvious that he is a highly skilled and imaginative cartoonist as well as a top-notch draftsman. He's in total command of the page, flipping between nuanced naturalism and crazed, cartoony expressionism with great ease — sometimes in the space of the same panel. He is a natural for receiving the Secret Acres treatment, getting top-notch design and production values from the wonderful publishing concern of Leon Avelino and Barry Matthews. What I'm not sure of at this point is if he's figured out what he truly wants to express through his comics, although hints of this are starting to break through in his newer stories.

This book is a collection of short stories, mostly collected from his minicomics. The earliest comics he did have the feel of extended style exercises. For example, "Turtle, Keep It Steady!" is a delightful class assignment from his time at the Center for Cartoon Studies that's a retelling of the fable of the Tortoise and the Hare. Here, the contest between the two is musical, as both animals are drummers. Turtle plays a steady, minimalist beat on a small drum kit, while the wild Hare comes along with a big, meaty sound that draws the crowd to him--until he gets drunk and distracted, and the steadfast Turtle wins the musicians' battle.  Lambert does a fine job evoking music by depicting notes as vibratory lines. This is a wonderfully whimsical little tale, which owes a lot to the clever way he solves storytelling problems. This story won him early notice, and was included in a volume of Best American Comics.

Lambert does a fine job evoking music by depicting notes as vibratory lines. This is a wonderfully whimsical little tale, which owes a lot to the clever way he solves storytelling problems. This story won him early notice, and was included in a volume of Best American Comics.

On the other hand, the titular story and "Everyday", while both gorgeous and evocative distillations of childhood rage in a fantasy environment, speak to the fact that earlier in his career,  Lambert started to repeat himself thematically without adding much that was new to the proceedings. Both see children raging against anthropomorphic suns in the sky, with earth-shaking results in both instances. Lambert wisely book-ends these stories at the beginning and end of the book, respectively, but the problem is that they're not nearly as compelling as the rest of the stories. In the opening and closing entries, the characters are caricatures, as interchangeable as video game characters. There's simply nothing at stake here.

Lambert started to repeat himself thematically without adding much that was new to the proceedings. Both see children raging against anthropomorphic suns in the sky, with earth-shaking results in both instances. Lambert wisely book-ends these stories at the beginning and end of the book, respectively, but the problem is that they're not nearly as compelling as the rest of the stories. In the opening and closing entries, the characters are caricatures, as interchangeable as video game characters. There's simply nothing at stake here.

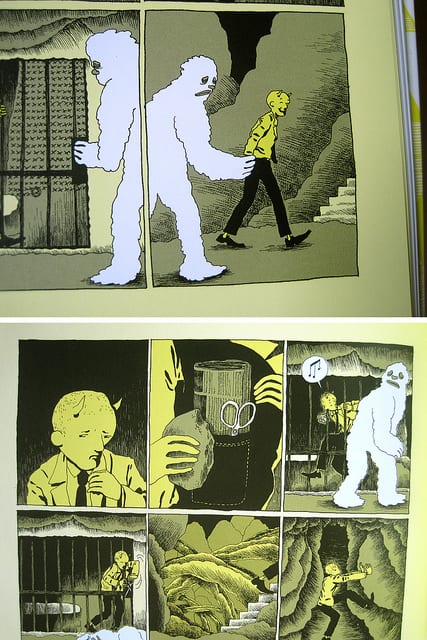

Contrast that with "After School Snacks", a story that at once is more inventive and intimate. It's a scatological tale of two kids in danger from two hungry & grotesque monsters, and Lambert introduces just enough small character detail to get the reader interested in their fates. At its heart, as in the aforementioned stories, it's about the emotions, fears, and fantasies of children writ large (in this case, the fear of having to defecate far away from home as well as being unable to communicate with one's parent). Lambert has always had a clever way of incorporating lettering into his storytelling, wherein the letters themselves are not only decorative and informative, but are also part of the raw stuff of the narrative itself. In this story, the monsters literally twist the words of the children to turn screams of alarm into reassuring conversation, so as to prevent being discovered by a parent. One of the best things about the story is that the children beat the monsters by being even more disgusting than they are.

"Too Far" mines similar territory but is far more raw emotionally. Here, the feelings of one young teenage boy are literally outsized, and the experience of a particular emotion makes him remember every other time he felt that emotion simultaneously. Lambert's manner of depicting this is clever, with a radial series of images not unlike the trails of an acid trip, and a distinct yellow & black color pattern. That fear then manifests even more dramatically when he is threatened by his father, causing him to devour him and then the entire world (eschatological escalation is a common story device in Lambert's work). The twist here is that Lambert shows us life inside the devourer, as whole societies spring up, until one day a descendant of his brother makes a journey to speak to the devouring boy. This casual exchange is the most extended sequence of pure emotion to be found in the book, and the fact that this is a more recent story speaks well of the direction Lambert may be heading in.

The remaining three stories in the book are all explorations of environments that double as ways for Lambert to work out storytelling challenges. "Mom Said" is yet another sibling battle comic by Lambert, with the yearning of a scolding older sibling to be part of his younger siblings' fun leading to the moon coming to their window in order to listen to music. Once again, sound effects take on a physical aspect in the story and kids suddenly grow gigantic in pursuit of their fun, but there's a slightly more emotional core to this story than some of the others. "PSR" is an incredibly clever game of "Paper, Rock, Scissors" played between a thieving little girl and the man from whom she steals ice cream. Lambert's visual approach is slightly different here, working much smaller (a nine-panel grid), and with an even finer line. There's a wonderfully vicious absurdity to be found in this story, as the devil-man manages to outfox a bizarre blobby jailer and the girl to finally get what he wants. "Caveman" is the rare full-color piece from Lambert; it involves the titular character navigating a dangerous landscape, including pterodactyls, bogs and the woman in the moon. The panel-to-panel logic reminds me a bit of Brian Ralph by way of Lewis Trondheim.

At the Center for Cartoon Studies, students are encouraged to publish as much as possible, but to do so with short stories first. Many students come in with an ambitious graphic novel or other long-form work in mind but don't have an understanding of just what it takes to complete such a project. Lambert is an artist who clearly internalized that lesson, trying to ascertain just what kind of cartoonist he is. I Will Bite You! has the feel of a thesis project with seeds of longer works with more complex themes. At this point, Lambert seems to be an artist who writes rather than an writer who draws. I'm curious to see if he has a long-form work in him that continues to expand on his themes of sibling rivalry, the viciousness of childhood, and the fluid nature of reality during childhood.