A difficult task: to tell a story in which there is no forward progress, no momentum, just drudgery and suffering. In a remote Nazi stalag with no hope of escape on the horizon, no possibility of rebellion, misery and ceaseless repetition are the only traits that distinguish each day. For Jacques Tardi, these are the qualities he must convey, to capture anything of his father’s internment during the Second World War: defeat, privation, punishing monotony. The artist’s byword, repeated again and again in his Comics Journal interview about his new book, and often in his father’s narration therein, is “bitterness.”

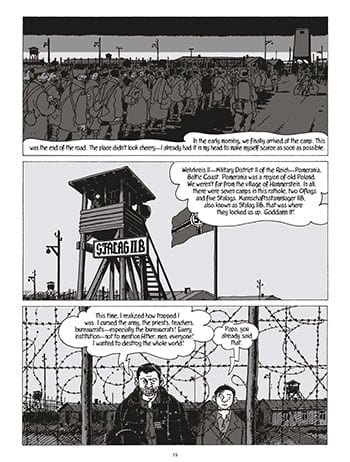

René Tardi had much to be bitter about, thanks to the nearly five years he spent in Stalag IIB, sixty miles south of the Baltic Sea, in what was then Pomerania, following his capture in the French defeat of 1940. “His youth had been confiscated,” writes his son in the foreword to the welcome new translation of 2012’s I, René Tardi, Prisoner of War in Stalag IIB, a “visual reconstruction” of his father’s military experience. (The second volume, 2014’s “My Return Home,” will appear in English early next year; Casterman lists a third volume in French this winter.) A professional soldier well before the war began, Rene endures the ignominy of a quick surrender in the early going of I, René Tardi, while the bulk of the book tolls out his years of bondage, hunger, and disgrace in the miserable German camp to which he is exiled.

“It lasted five years!” René erupts, late in the book, when his young son complains that he’s repeating himself. “Let me talk about it, damn it! My belly was hollow for five years! Shit!” And talk about it he does: Tardi has adapted his father’s story in the sombre, three-tiered, grey-toned pages familiar from his masterpiece of World War One, It Was the War of the Trenches, but here these widescreen compositions are clouded with captions filled to bursting with René’s anguished ruminations and detailed recollections. In the 1980s, not long before his death, René filled notebooks with his memories of the stalag, illustrated with “explanatory sketches” and crammed with an almost numbing wealth of information about camp life.

“It lasted five years!” René erupts, late in the book, when his young son complains that he’s repeating himself. “Let me talk about it, damn it! My belly was hollow for five years! Shit!” And talk about it he does: Tardi has adapted his father’s story in the sombre, three-tiered, grey-toned pages familiar from his masterpiece of World War One, It Was the War of the Trenches, but here these widescreen compositions are clouded with captions filled to bursting with René’s anguished ruminations and detailed recollections. In the 1980s, not long before his death, René filled notebooks with his memories of the stalag, illustrated with “explanatory sketches” and crammed with an almost numbing wealth of information about camp life.

Tardi draws on these resources in his recreations here, almost too deferentially. In everything from accounts of how the huts smelled (like feet and farts), to the ways that goods were smuggled in (through prisoners employed as slave labour on neighboring farms), to descriptions of the prisoners’ grueling punishment (drilled relentlessly with bags of bricks strapped to their backs), to the combined effects of an impoverished diet and open, improvised latrines (“impossible to escape this calamitous diarrhea”), the artist’s cartooning does not bring his father’s words to life so much as it gives them a space in which to exist. Tardi’s drawings merely conjure the world in which history has happened, rather than animating actions within that world. (With a handful of exceptions, of course: When René skirmishes with Panzers, or when he’s farmed out to go harvest potatoes, desperate to escape or at least to steal crops, you can sense Tardi revving his action comics engine.) In contrast to the way that, say, Art Spiegelman or Joe Sacco break down the memories of Vladek or Šoba into moment-to-moment cartooning sequences, Tardi’s panels work instead in generalities, and let his father’s wordy narration handle the particulars.

The cartooning works like a series of snapshots, rather than a film. This is often a book of murky, muddy landscapes and crowd scenes full of indistinct faces—clinical, accurate, historical, but passionless. Still, what snapshots Tardi provides. His tanks and buildings could be driven or lived in, and his drawings of carnage, viewed from a curiously impersonal distance, are nonetheless as vivid and quietly distressing as ever. Desolate battleground vistas play host to sprawled soldiers, bullet-riddled machinery, farm animals left for carrion, an overturned pram in the rubble, a woman’s corpse close beside it. There are wooden carts plump with Russian cadavers, wheeled through the camp in secret. Grinding a German cannon crew beneath the treads of his tank, René recalls leaving merely a “soup of bodies… A bloody magma…” which Tardi renders as a bedraggled stew of inky offal, nearly indistinguishable from the slop and shit that slosh around every other scene.

The cartooning works like a series of snapshots, rather than a film. This is often a book of murky, muddy landscapes and crowd scenes full of indistinct faces—clinical, accurate, historical, but passionless. Still, what snapshots Tardi provides. His tanks and buildings could be driven or lived in, and his drawings of carnage, viewed from a curiously impersonal distance, are nonetheless as vivid and quietly distressing as ever. Desolate battleground vistas play host to sprawled soldiers, bullet-riddled machinery, farm animals left for carrion, an overturned pram in the rubble, a woman’s corpse close beside it. There are wooden carts plump with Russian cadavers, wheeled through the camp in secret. Grinding a German cannon crew beneath the treads of his tank, René recalls leaving merely a “soup of bodies… A bloody magma…” which Tardi renders as a bedraggled stew of inky offal, nearly indistinguishable from the slop and shit that slosh around every other scene.

Through this quagmire, on every page, René wanders and pontificates, accompanied—somehow—by his son, who was only born after the war had ended. The timeframe of the book is complex, its point of view subtly refracted through several decades’ remove and multiple different points of view. The Tardi of the present day draws his father in the 1940s. The twenty-something René narrates from the vantage point of the memoirs he penned decades later. The soon-to-be-father serves as guide to a boyish and petulant Jacques, as the artist would have appeared around 1960. At times, the way Tardi superimposes these temporalities on top of each other conveys a dizzying sense of the nightmare of history: as young Jacques strolls impossibly through the ruined hellscapes of World War Two, under blood-red skies, Tardi communicates how much the past persists into the present, and how his father’s ghostly memories shaped and colored the artist’s own life.

The rapport between father and son is captious at best. For much of the first third of the book, René is hardly visible at all. Instead, his voice emerges from deep inside a tank—an ancient Renault FT17 or a powerful R39, like the ones he piloted in combat—and it is these hulks of impersonal machinery young Jacques converses with. It’s an apt figure for the pair’s relationship: the father inaccessible, ensconced within his wartime experiences, relating to his son only through that hardened exterior. Once the French are defeated, René at last emerges from his machine, almost as though, as the book wears on and Rene’s hardships increase, Jacques comes literally closer to his father. To keep himself occupied in the camp, René draws, just as Jacques will later do, and hand-carves from wood scraps a cigarette case in the shape of a pelican—the beast fabled to feed its young from the flesh of its own breast. We might reflect that René likewise suffers so that Jacques may yet live, but René thunders that he suffers for no reason.

The rapport between father and son is captious at best. For much of the first third of the book, René is hardly visible at all. Instead, his voice emerges from deep inside a tank—an ancient Renault FT17 or a powerful R39, like the ones he piloted in combat—and it is these hulks of impersonal machinery young Jacques converses with. It’s an apt figure for the pair’s relationship: the father inaccessible, ensconced within his wartime experiences, relating to his son only through that hardened exterior. Once the French are defeated, René at last emerges from his machine, almost as though, as the book wears on and Rene’s hardships increase, Jacques comes literally closer to his father. To keep himself occupied in the camp, René draws, just as Jacques will later do, and hand-carves from wood scraps a cigarette case in the shape of a pelican—the beast fabled to feed its young from the flesh of its own breast. We might reflect that René likewise suffers so that Jacques may yet live, but René thunders that he suffers for no reason.

His words vibrate with anger throughout, disgusted with the whole enterprise of war, especially the cravenness of its upper-class architects and bourgeois bureaucrats, “the imbeciles in charge.” At times René’s biliousness (ably translated by Jenna Allen) approaches the blunt and scathing vitriol of Tardi’s great model, Céline, who characterized the First World War as “[a] vast and universal mockery.” Here is René, recalling the POWs’ cramped transportation by rail, plagued with sickness and hunger, deep behind enemy lines:

Since you can’t kill the guy with the runs, you curse the train car, your friends, France, politicians, the Boches, the whole world. You want the Earth to explode and for there to be nothing left. You curse men sleeping in their own beds, far from the stench of shit. You cannot close your eyes without thinking about your recent defeat, your slavery that’s only just begun. And the fact that without food or water, you’ll have to rub shoulders with the assholes taking up space in the car, whom you would never have wanted to meet. I hated all of them.

Here is bitterness made palpable, conjuring a world of ever present hunger, shit, and struggle—an existence defined, for years to come, by sombre, impotent desperation.

Tardi succeeds in creating a work that is true to that stalled and galling sense of bitterness—bitterness about the shame of surrender, about France and the myths of patriotism, about the human capacity to inflict suffering. But while he successfully replicates the drudgery and monotony his father suffers through, his work can neither transcend nor transform it—but neither does Tardi intend to do so. Life in the stalag cannot be transcended; enough, for us, that Tardi can haul it out of the morass of history, wipe some of the muck from its features, and make it concrete. It will not—it cannot—be pleasant. It can only be endured.

Tardi succeeds in creating a work that is true to that stalled and galling sense of bitterness—bitterness about the shame of surrender, about France and the myths of patriotism, about the human capacity to inflict suffering. But while he successfully replicates the drudgery and monotony his father suffers through, his work can neither transcend nor transform it—but neither does Tardi intend to do so. Life in the stalag cannot be transcended; enough, for us, that Tardi can haul it out of the morass of history, wipe some of the muck from its features, and make it concrete. It will not—it cannot—be pleasant. It can only be endured.