TW: This article discusses sexual violence.

The Biblical story of Susanna and the Elders was a popular subject for artists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the story, two older men spy a young woman bathing in a beautiful garden and, captivated by her beauty, attempt to rape her. She resists and escapes, and the men accuse her of adultery and bring her to trial. She is sentenced to death, but another man proves her innocence right before the execution, saving Susanna’s life and honor.

Tintoretto, Rembrandt and Rubens painted Susanna as a sensual, fleshy nude, emerging from her bath and surrounded by foliage, jewels, and Cupid statues. She often looks afraid to find a couple of creeps groping at her from the bushes, but she still always manages to look sumptuous and vulnerable, made by and for the male gaze.

Roman painter Artemisia Gentileschi’s interpretation of Susanna and the Elders in 1610 is a drastically different scene. There is no water or flowery garden; Susanna sits on a hard marble bench and her discomfort and fear are palpable. She shields herself from the elders, who hulk over her like a dark cloud, sinister and plotting. It is Gentileschi’s first known painting, completed the year she turned 18.

Since her death c.1655-56, much interest in Artemisia Gentileschi has been centered on an episode in her young life: around the time she painted Susanna, she was raped by the artist Agostino Tassi and endured an eight month trial during which she was tortured to prove that she was not lying. Agostino was found guilty and briefly imprisoned, and Artemisia was associated with the notorious trial and its implications for the rest of her life and beyond. Around 1610 and a decade later c.1620, Artemisia created two versions of her most famous painting, Judith Slaying Holofernes, a gruesome depiction of Judith beheading the man who betrayed her.

Plays, films, and novels have portrayed Artemisia as a passionate artsy type who falls in love with the “bad boy” (after the assault she began a consensual relationship with Agostino, who had promised to marry her and restore her honor). In Agnes Merlet’s bewildering 1997 film Artemisia, Agostino and Artemisia make passionate, candlelit Baroque love, he teaches her how to paint perspective properly, and the trial proves his innocence; adaptations of Artemisia’s story have often taken such creative licenses. Artemisia Gentileschi’s legacy as one of Caravaggio’s most important contemporaries has historically been overshadowed by this story, but her work is inextricably linked to it; women were the subject of almost all of her paintings, and she painted them in moments of strength, resistance, and suffering.

The new graphic biography I Know What I Am by Gina Siciliano is a visual biography of Artemisia Gentileschi for our times, and a moving tribute from one female artist to another. Renewed interest in Gentileschi has emerged in the last few years, and this summer the National Gallery in London will host a major exhibition of her work, titled Artemisia. It should be noted that Siciliano spent seven years writing I Know What I Am; the book is timely, but not trendy. It is thoroughly researched, and includes 40 pages of notes and an extensive bibliography at the end. Siciliano documents the minutiae of her process, as if to challenge anyone who might question the accuracy of her account. “Readers can trace all my decisions if they want to,” she says of her painstaking documentation. In this way she makes the “unseen” work of this major project seen, just as she illuminates the multitude of personal and creative decisions that Artemisia brought to her paintings.

In the form of a comic, Artemisia’s life is captured in a new way. The narrative text offers a comprehensive history lesson, while the dialogue and imagery draw directly from visual and written sources. A lifetime of painting is conveyed through Siciliano’s own art, and the most important scenes slow into dynamic arrangements of panels. Siciliano has been making comics for two decades, but this is her first long-form work. She chose to write a comic in order to create “a more comprehensive picture,” and even her notes section is illustrated.

Siciliano incorporates translations of primary sources into the dialogue, and reading the exact words of recently discovered letters written records from the trial is an especially powerful experience. The book is densely drawn and text-heavy, and it relates the complete life of a woman who lived through an extraordinary amount of history, who made excruciating sacrifices for her art as a single mother, and who became the first woman accepted to the prestigious Florentine Academy of Fine Arts. Artemisia faced the challenges of being a female artist in any era, as well as the unique challenges of life as a woman and artist in 17th century Italy. Siciliano begins the book with descriptions of the intense violence, paranoia, and persecution of Reformation era society, which “popularized notions of fantastic suffering and triumphant martyrdom” (p. 6). This is a society in which women painters were seen as “miraculous freaks of nature” (p. 26), often required to earn income for their families while still taking on their domestic responsibilities, which meant “living in a constant state of pregnancy” (p. 26). Artemisia lived most of her life under financial strain and supported herself and her children, several of whom died in childhood, which was very common. As a woman, she was no stranger to “fantastic suffering.”

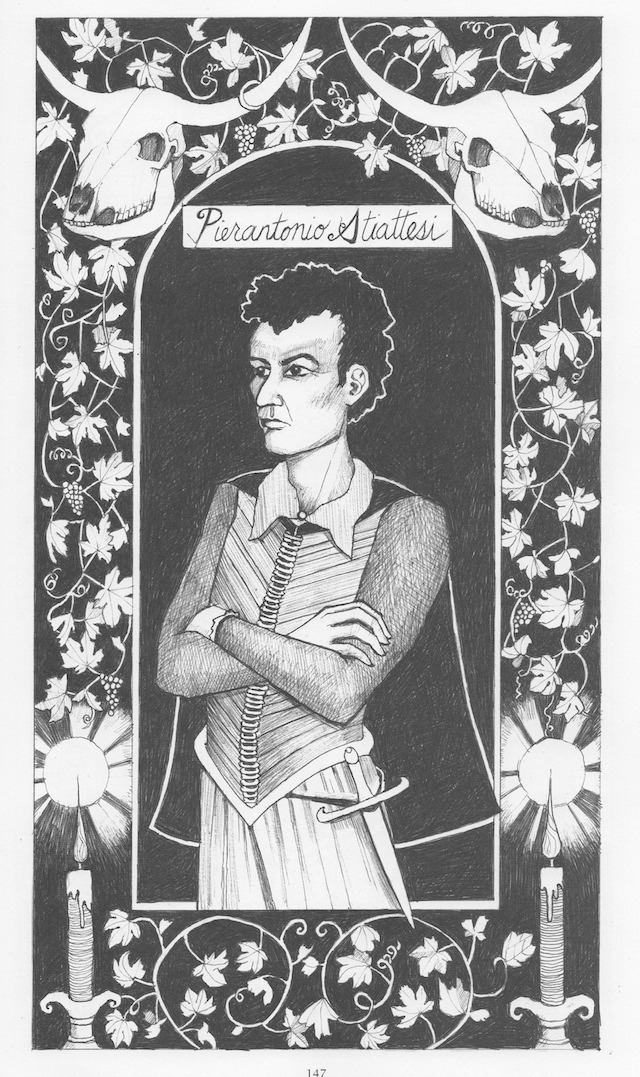

Over the course of her lifetime, Artemisia traveled frequently and encountered a number of personalities, including various members of the Medici, prominent artists and patrons, and even Galileo. In the book, which is drawn (somewhat regrettably) entirely in ballpoint pen, each character is introduced in a full-page portrait surrounded by an ornate border of symbols, objects, and patterns. These are some of Siciliano’s strongest illustrations, but much of the drawing in the book is a bit clunky; faces and figures are often stiff and inconsistent, especially in the more expressive and active scenes. The illustrations do improve over the course of the book, however, and you would expect a seven-year project to come with technical improvement. The most compelling drawings are Siciliano’s copies of Artemisia’s paintings, which are truly stunning; the detail and chiaroscuro are beautifully rendered in crosshatch. The decision to draw these complex paintings so carefully (instead of incorporating photos or creating simpler renditions) is a fitting tribute to Artemisia, who likely would have learned to paint by copying the “Old Masters” before her.

In the introduction, Siciliano explains her interest in Artemisia, as a fellow survivor of sexual abuse. “So much has changed since Artemisia’s time, but in some ways very little has changed,” she says of the way survivors are questioned and judged by society as well as legal systems. “A lot happened to me during those seven years… Through it all, I knew I could escape into this other world, with Artemisia as my lifeline. Artemisia, her art, and her world sustained me.” Siciliano, in living alongside Artemisia and producing this rich, honest biography of her life, offers a deep, enduring homage to a brilliant painter and a remarkable woman.