In his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, Bob Dylan née Zimmerman writes about visiting the New York Public Library as a recent émigré to that city. While there he receives a vision: “the full complexity of human nature … the godawful truth,” which becomes the "template behind everything I would write.” He says what he learned he locked away so he “could send a truck back for it later.” Of course it’s not what he finds that makes Dylan Dylan it’s what he does with it, the fiction he creates from fact.

Luke Healy must have hired the same moving company as Dylan for How to Survive in the North. Healy uses a similar technique of looking ahead while being informed by the past. Instead of a descent into the antebellum South, Healy heads north to Alaska with a stopover in the colder climes of Hanover, New Hampshire. Healy tells two true tales of arctic adventurers and another story, a made up one, about a morally indolent academic. Like the folksinger from Duluth by way of Hibbing, Healy pursues the complexity of human nature. Yes, yes, truth is and always will be stranger and more shocking and surprising than fiction, but fiction leavens (real) life, makes it livable. Recovering history requires a translator, a go-between to show how fact—especially the little known and under-reported kind—earns its distinction over fiction. It takes a Dylan-type like Healy, a storyteller, to remind us of our complexity and how the human capacity to inspire and endure runs counter to our need to destroy and to fuck up everyone and everything. It’s a wonder we survive at all.

In the hands of a lesser humanist than Healy such a Baedeker to how humans overcome stupidity, greed, and pride could come off as barrel-aged bile soaked in cynicism, or worse, given that it’s a retelling of historical events, as dry as dust. Dragging discarded historical tidbits into the light requires nimbleness and ruthlessness, too much of one or not enough of the other and either the point is lost or it drowns in detail. Healy’s stories work because he keeps his storytelling simple even though the subject is far from it. The simplest words, chord progressions, and images are often the most effective in conveying complex ideas. See Chuck Berry, Etta James, Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson, or the paleo-cartoonists who drew on the cave walls of Lascaux. Sometimes all it takes to get the point across, or better, to make the audience feel something is a few well-placed notes or lines. How to Survive in the North is the harshest trip the Peanuts gang never took.

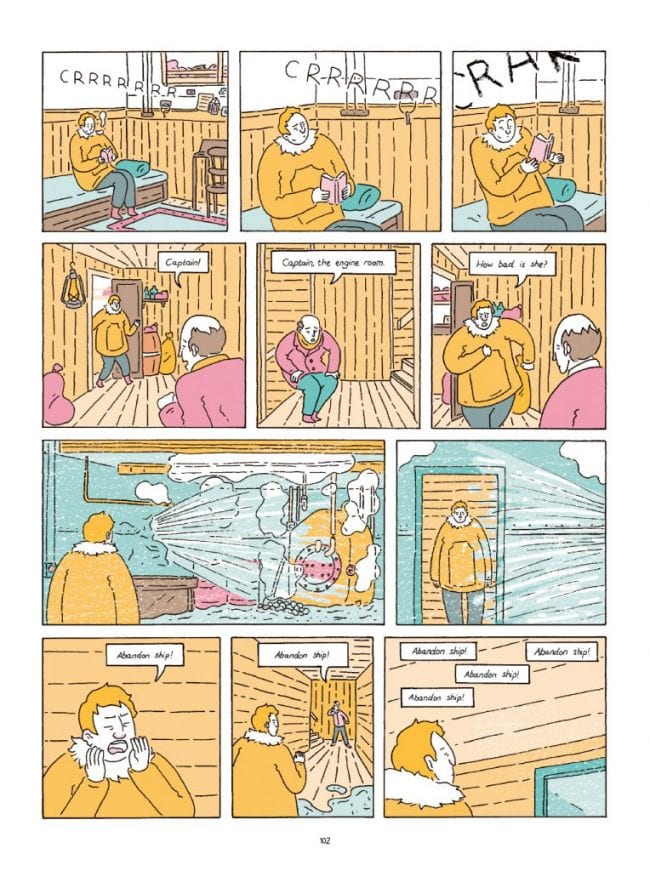

Healy deals in emotions. He understands the reader’s knowledge or interest in early twentieth century arctic exploration runs a distant second or third to developing characters and creating empathy. In the parlance of our times, ‘the feels.’ Healy is ‘feels’ all over. Which is where the writing and the cartooning conflict. With its slight lines, clean page and panel layouts, and uncluttered backgrounds, the preciousness of Healy’s art can overwhelm the story’s richness and what’s at stake—ragged emotion sacrificed for visual efficiency. Such a charge sounds like complaining to the chef with a mouthful of food. It is. It’s also wanting a mouth to look like more than a dash and an eye to not be confused with a dot. Healy has a style, a look, for you more academic types, a gestalt. And, yes, it works (to a degree). It’s too bad it’s all so dear. Unless that’s the point?

The first historical account Healy recalls focuses on an arctic expedition led by Vilhjalmur Stefansson in 1913. To say Stefansson ‘led’ the expedition is a kindness Healy barely cops to, ‘financed’ and then ‘abandoned’ halfway in comes closer to the telling. The hero of the 1913 narrative is Captain Robert Bartlett a/k/a ‘The Ice Master,’ if, as Healy points out, you trust Newfoundlanders. As stolid and deep as the wilderness around him, Bartlett is what’s expected in a story about old-timey explorers and the insurmountable odds they face.

Counter to Bartlett’s alpha male is Ada Blackjack, the hero of the second historical narrative. A native Alaskan woman, Blackjack signs on as a seamstress to a 1921 expedition to claim, as the leader of the expedition tells her, “a little spit called Wrangel Island” for Canada. Blackjack plays POSSLQ in this all-male expedition which includes (spoiler) a member of Stefansson’s 1913 expedition and a perpetual grump, Lorne Knight.

Healy’s introductions to Bartlett and Blackjack show an economy in storytelling to match his drawing. Within a couple of pages and a handful of panels, Healy demonstrates how these characters will use opposing strategies to survive. Bartlett commands. Blackjack demurs. Neither strategy is better or worse. Survival results from endurance, and the method means nothing. Nature endures; humans, most of the time, do not. The arctic doesn’t care for theories, thoughts, or emotions, only practicalities. The survival of these characters depends on their natures, what they bring with them. What they pack. By setting his comic in a harsh climate, Healy plays with ideas of nature vs. nurture or determinism vs. free will, God or nothing. Blackjack plays timid, but that’s her nurture not her nature. When it comes to these historical figures, Healy sides with fate. The how these people survived or died was on them. The cold (nature) of the arctic brings out something in a person, sharpens them, but it can’t hone what isn’t there. Nature needs an edge in want of a good grinding.

Healy’s introductions to Bartlett and Blackjack show an economy in storytelling to match his drawing. Within a couple of pages and a handful of panels, Healy demonstrates how these characters will use opposing strategies to survive. Bartlett commands. Blackjack demurs. Neither strategy is better or worse. Survival results from endurance, and the method means nothing. Nature endures; humans, most of the time, do not. The arctic doesn’t care for theories, thoughts, or emotions, only practicalities. The survival of these characters depends on their natures, what they bring with them. What they pack. By setting his comic in a harsh climate, Healy plays with ideas of nature vs. nurture or determinism vs. free will, God or nothing. Blackjack plays timid, but that’s her nurture not her nature. When it comes to these historical figures, Healy sides with fate. The how these people survived or died was on them. The cold (nature) of the arctic brings out something in a person, sharpens them, but it can’t hone what isn’t there. Nature needs an edge in want of a good grinding.

If the nonfiction of How to Survive in the North is a harsh schoolmaster than its fiction is lunch, less rugged for sure, but in Healy’s estimation twice as cruel and more vicious by half. This third story takes place in 2013 and centers on sad sack academic, Sullivan Barnaby, a professor at Dartmouth College who’s in the midst of a pseudo-sabbatical due to an investigation into if he’s done something untoward with one of his students, Kevin. He has/is. To make matters worse only one of them is in love and it ain’t the Dartmouth frat boy. The stakes are always higher when pathetic is added to tragic.

Turns out a previous occupant of Sully’s Dartmouth office was one V. Stefansson (see above). Which sends Sully to the library (nerd!) to get in out of the cold and let the balm of research distract him from his troubles. Sully’s investigation provides a gloss that tethers the reader to the book’s overarching themes of reluctance, loneliness—especially in company of others—and self-destruction. It’s also a too convenient way to tie the real-world events of the other two narratives together. In a book that’s as sophisticated and rigorous as this, such a ham-handed technique sticks out like whatever is the opposite of a polar bear in a snowstorm. Unless … like the art, Healy hides his purpose in plain sight.

Sully is an alloy of modern ennui. Over-educated, overweight, and mentally and physically unable to connect with others in the meatspace of real life. He’s loathsome and loveable all at once. He lies to his friends, to himself, and he’s allowed to go on, to survive, in spite of his actions. Why? Well, it’s probably got something to do with the fact Sully is fiction and it’s his story that keeps How to Survive in the North from becoming a charming tale of people and places you never knew existed. Healy uses fiction as the control to demonstrate what survival, real survival, truly is. History is fixed, static, whereas fiction is elastic, changeable. Healy sees fiction as a chance to change the story instead of being a (real life) victim of chance, fate. Fiction isn’t life or death, its make-believe, a soft landing in a real world of hard surfaces. For Sully the struggle is real. No, it’s not what Bartlett and Blackjack faced, but Sully’s predicament is more relatable (somewhat) to the reader than what it must really be like standing up to a polar bear or trekking across a frozen wasteland. Sing it, write it, draw it, however it happens, that’s the fact of fiction and the best way humans have to survive those ‘godawful truths.’

O.K., the art, which I’m as reluctant to write about as Blackjack is to go on the expedition to Wrangel Island. Like her I need the money so … Healy’s art pairs with his simplified-approach-to-complex-ideas aesthetic like sealskin mukluks and a trimmed parka. Panel to panel he’s perfect and there’s never any confusion as to who’s who and what’s happening as he weaves between stories. But that’s the standard, right? The “do-your-job” part of the equation. What tempers my enthusiasm for How to Survive in the North has less to do with how well Healy does his job. If it’s possible to see the craft, the degree of meticulous care to which an artist brings to the subject and how everything fits it all together and still want the art to be … I dunno? … different that’s where this book leaves me, not cold or lukewarm (too cute, I know), but conflicted, even if mildly so.

I wish I could put my coolness down to personal preference, but it’s not as simple as that, it’s more systemic. When a similar-looking squiggle stands for a cloud, a snow drift, wrinkles in fabric, and waves and every edge, every line looks imperfectly perfect—and don’t get me started about how Healy renders wooden surfaces like they’re long stretches of Morse code—something gets lost. On an intellectual level, Healy’s art is spot on, yet it misses in connecting at the emotional level. Which is conflicting and frustrating because the writing succeeds in both aspects. I recognize how the lines vibrate with the punishing monotony of the arctic and the routine of modern life. Healy has so thought out his diabolical device of same sameness that the panels and page layouts echo with the same repetition. Each panel is as evenly structured with the likewise hard-edged symmetry of its neighbor, a complement to the squiggles, round-edged figures and coded woodwork therein. Step back and observe how methodically Healy lays out each page and you see how the intervening row of panels is slightly offset to the row above and below which perfectly fall in line with one another, a planned development of a page. Brilliant. And yet in each instance when Healy raises his gestalt to near golden ratio-like levels, I check.

When Healy art isn’t doubling as an endurance test, there are brief moments when he lets the page breathe. There’s an image early on when Bartlett is rowed out to the ship for the first time that’s breath-taking in its scope and captures the feeling at the outset of the adventure. And it fills the top half of an entire page! Healy doesn’t change his style per se, more like he diversifies, clouds become puffy instead of looking similar or exactly like the waves. He draws the wake of the rowboat as it splits the water and Healy’s signature wood grain is confined to the rowboat while the planking of the off-in-the-distance ship is left plain. Later Healy composes a panel with the ship and her crew that’s as close as he gets to a God’s eye view. It devastates in how perfectly chosen it is to impart the scale of nature and the fragility of humans. It’s these moments of release amongst the tension that makes How to Survive in the North so tough to quit and gives it something of an explorer’s valor in spite of the odds.

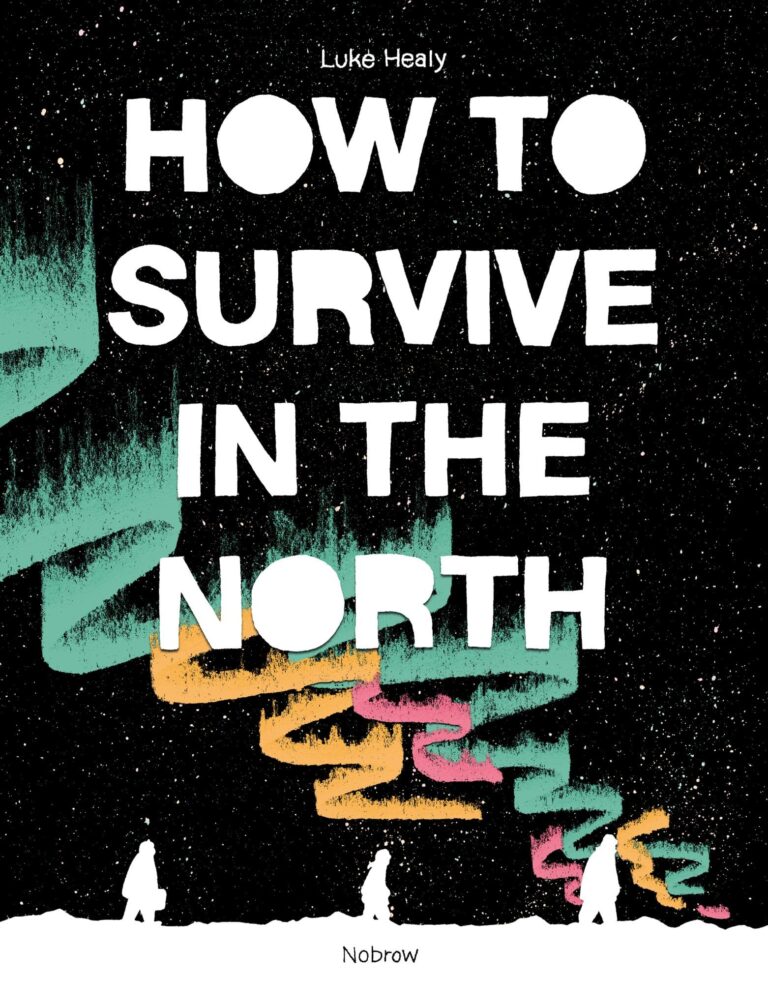

If the cartooning is a test of will there’s also the coloring. Again, Healy’s use of color attains the cerebral rigor and merciless efficiency. Stark. Beautiful. Distant. It’s a limited color palette—because of course it is—of mint greens, lemon yellows and salmon pinks, soothing and the appropriate cheery charm of waiting rooms or hospital hallways. The coloring acts as the shuttle in the loom as Healy weaves together the three narratives. Practical and efficient. With the exception of the inking and the pleasing blobs that pass as hair Healy mutes the use of black especially when it comes to the sky. The exception is an illustration of the Aurora Borealis (which is appropriated for the book’s cover as well) that breaks up a prologue showing each of the main characters at their narrative nadir. This illustration of green and yellow ribbons rippling across a star-pocked sky speaks to the poetry of How to Survive in the North. Perhaps the reason Healy chooses to drape the sky in shades of salmon and mint instead of black is the same reason the lived-in clean lines of his cartooning captivates more than it curdles. To do so is too much, inefficient, a flaw in the flawlessness. To hang all that black in the sky—with all that snow on the ground, think the contrasts, children, the contrasts!—would crush these poor souls and don’t they have enough to put with?

History engenders grace. Real life accounts of exploration include indescribable instances when some outside influence, some cosmic tumbler, turns: water is found or a fever miraculously breaks. Is it by chance or providence? The most tangible examples of grace in How to Survive in the North come from supporting characters (somewhere a more able critic will give these sidekicks a better vetting than my poor powers can muster). Without their intervention each story ends up as a solipsistic slog and we’ve enough of those. I bring this up so late to ask the question I’ve wrestled with as I’ve been writing this review: Does Luke Healy believe in God? The work provides proof Healy believes in grace. But what does he consider its source? The power of How to Survive in the North rests on such a question. It’s why I started with the story about Dylan. If there’s ever been an explorer, an artist, who’s tried to find the source of grace, it’s Dylan. Healy’s cut from similar storyteller’s cloth. There’s a lot to pack (and unpack) in order to make such a journey. Simple, no?