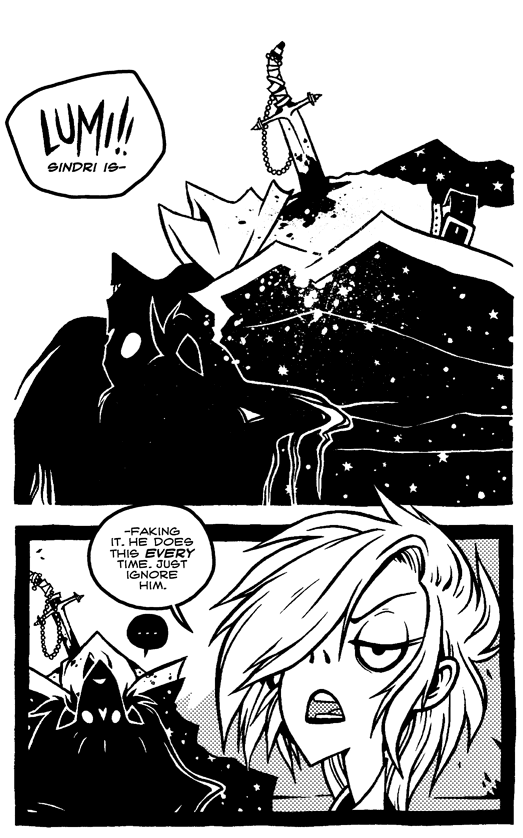

Hemlock is a sweet but somber Slavic-inspired fairy tale drawn by Josceline Fenton, a longtime cartoonist and animator. Hemlock follows a young 19th-century witch named Lumi and her accidental human-turned-frog familiar, Tristan, as they deal with her accursed unwilling marriage to Baba Yaga’s firstborn son, Sindri. Outcast by the Court of Witches and King Simo, her brother-in-law, Lumi wanders the outskirts of society, traveling in her house-snail, selling fertility spells in exchange for spices and baby teeth that can be used to summon up rudimentary Old Magic. Most of her time is spent concocting hemlock-heavy poisons to keep her evil husband Sindri sedated, at the threatening request of King Simo, but Sindri has developed a tolerance to his wife's poisons, and his awakening presence is bound to cause problems for Lumi and his brother rival Simo.

While many of the main cast members, including Baba Yaga and her three servants, hail directly from old folklore and communicate with some of the lyrical syntax of their traditional origins, Lumi and Tristan provide a more contemporary entry point for readers with their modernized witty language. Tristan’s constant anxiety and Lumi’s melancholic but outspoken personality combine into a charming rapport that complements the comic's unhurried pace. Slow pacing and indulgent, unnecessary scenes are a common pitfall in webcomics, given that they’re frequently created and updated in real time, without time to reassess and edit, and often with little or no buffer. Hemlock doesn’t stagger but keeps a steady, measured pace. Still, the lack of intensity and unchanging tempo make for a sometimes tedious narrative simmer. This pace is no doubt intentional on Fenton's, mirroring the storybook mood of Lumi’s wistful but tense and long-lived life.

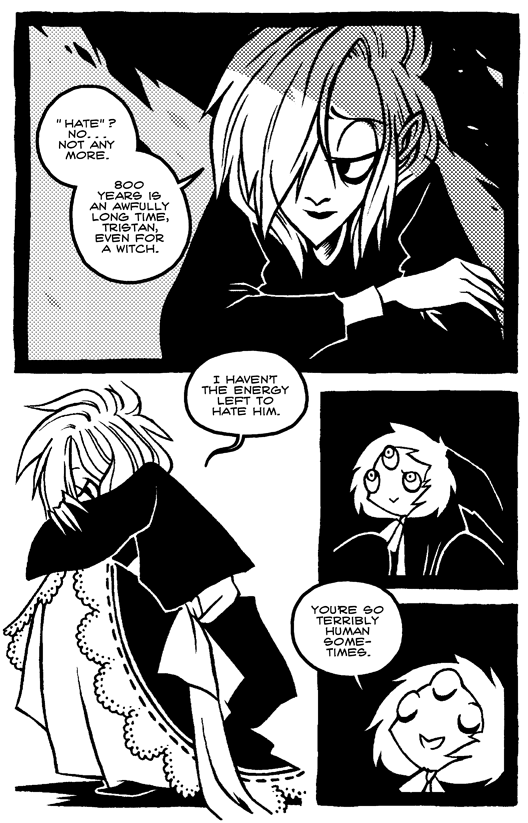

Fenton’s inking style is controlled and has grown tighter and cleaner over the years, each brush line smooth and carefully tapered, with the overall feeling of wholeness that one might see in a woodblock print. The linework seems to bleed into itself at the figures' heavier or shadowed junctures, as if pressed starkly into the page. Fenton cites Aubrey Beardsley as one of her inspirations and while her linework lack the delicate airiness of the 18th-century illustrator, her penchant for tightly inked spot blacks on thoughtfully designed and patterned clothing recalls her predecessor and shines throughout the story. Mike Mignola also comes to mind with his use of minimal composition and heavy blacks to translate pervasive darkness as ambience and to signal scale and space, cavernous voids.

Her character design style leans heavily on caricature, with small features punctuated by expressive bulging eyes, harshly tapered teardrop faces, and decisive, shapely silhouettes. Integrating such a flattened graphic style into a comic can be challenge, especially when trying to depict scale and space within a comic’s planar environment. Fenton opts for an atmospheric approach, often simplifying environments to their bare silhouettes and textures, and adding layers of SFX to signal busy crowds, the rush of wind through the woods, the creaking of the monstrous husband’s house.

As Hemlock approaches the finish of its fifth chapter, Fenton’s writing has become more resolute in its pacing, her characters' voices hold a sharper clarity. Her art, too, has become sharper and cleaner, which is most likely a product of her intensive animation work and not the most appealing development in her work. Previously, her use of screen tones often enhanced the texture of her linework and added to the depth of environments, but has now fallen to become a more ancillary technique.

While this genially grim folkloric narrative doesn’t have much in the way of action or in-depth worldbuilding, the story satisfies and enchants in a gently amusing way. Fenton’s storytelling hones into the particulars of the unique dynamics her characters find themselves in, like when Lumi poisons her husband as nonchalantly as one might prepare dinner, or the way Tristan deals with his new role as a magic frog familiar—and friend to a woman who is not his mother for the first time. The insight Fenton has into her characters, and her dedication to following through on the truth of their natures without forcing them into the familiar romantic tropes of folkloric narratives, is continually compelling.