For my money, the late Victorian-era ghost stories of Montague Rhoades James, aka M.R. James, are without peer. The classic scenario of his tales is that of a comfortable, upper-middle-class academic gentleman, who, through his own scholarly curiosity and/or carelessness, unwittingly invites a dreadful supernatural entity into his tranquil, privileged existence, an entity that brings with it terror, madness, sometimes even death. James' narrators relate these tales calmly and matter-of-factly, in a brandies-by-the-fire tone, as reality is slowly engulfed in otherworldly malevolence, incident by incident. The stories perfectly combine uniquely cozy British wit with mounting dread. Though typically noted for their restraint and chilling subtleties, James’ tales also feature flat-out horror. Some climax with appearances by monstrous spiders, a hairy demon, or a toad-like horror; others end in gory death as James reveals what has been lurking just off-camera all along: within that ash tree, underneath that ancient tomb, or in the shadows of that old rose garden.

As with the first edition, this second SelfMadeHero volume of James adaptations by Leah Moore and John Reppion features four stories. They are "Number 13," "Count Magnus," "Oh, Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad" (along with “Casting the Runes," this remains James’ most celebrated story), and "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas," each illustrated by a different artist. While the book is a good introduction for James novices, there's a buttoned-downed approach to the art that keeps it from truly excelling.

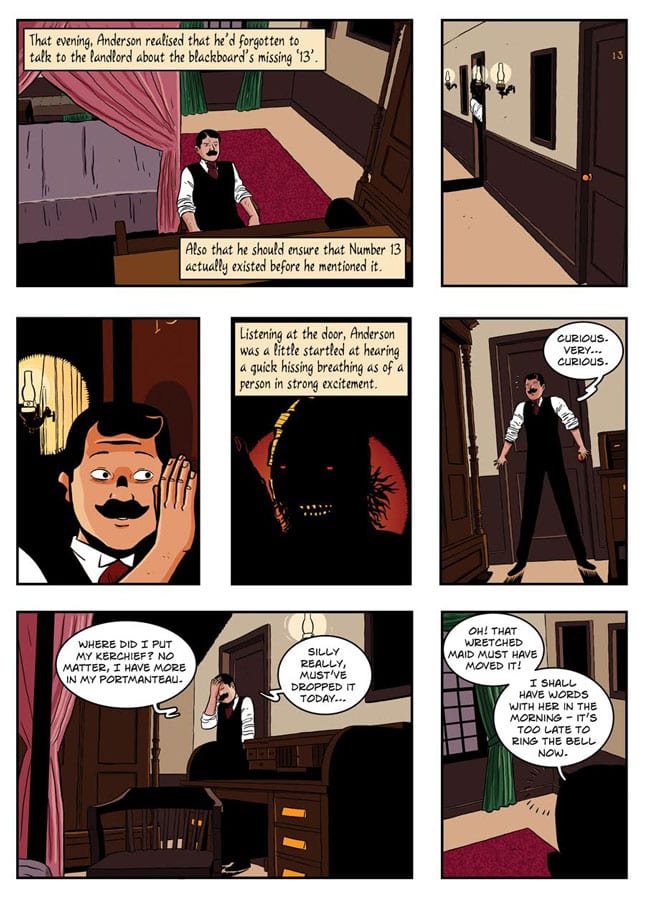

The first tale, "Number 13," is about a Mr. Anderson, who comes to the Danish town of Viborg to conduct historical research. While staying in a hotel’s Room 12, he hears disquieting noises coming from next door, Room 13—a room that seems to disappear during the day, only to reappear in the dark of night, for diabolical reasons. As stated in the forward by Jason Arnopp, "Number 13" lends itself to visualization particularly well and artist George Kambadais ably delineates the tricky spatial properties that are key to its effectiveness.

In "Count Magnus," a Mr. Wraxall pokes too deeply into the tomb of an evil 17th-century nobleman and lives to dearly regret it as he is relentlessly pursued thereafter by a pair of shadowy figures—figures that only Wraxall can see. Rod Serling, musing about the different types of fear—which he did often during the years spent working on his legendary Twilight Zone television series—wrote, "The worst fear of all is the fear of the unknown working on you, which you cannot share with others." What makes this particular terror so effective is that it isolates the protagonist character, increasing his or her vulnerability (as well as audience sympathies). As Wraxall’s pursuers close in on him, he can do nothing else but “lock his door and cry to God.”

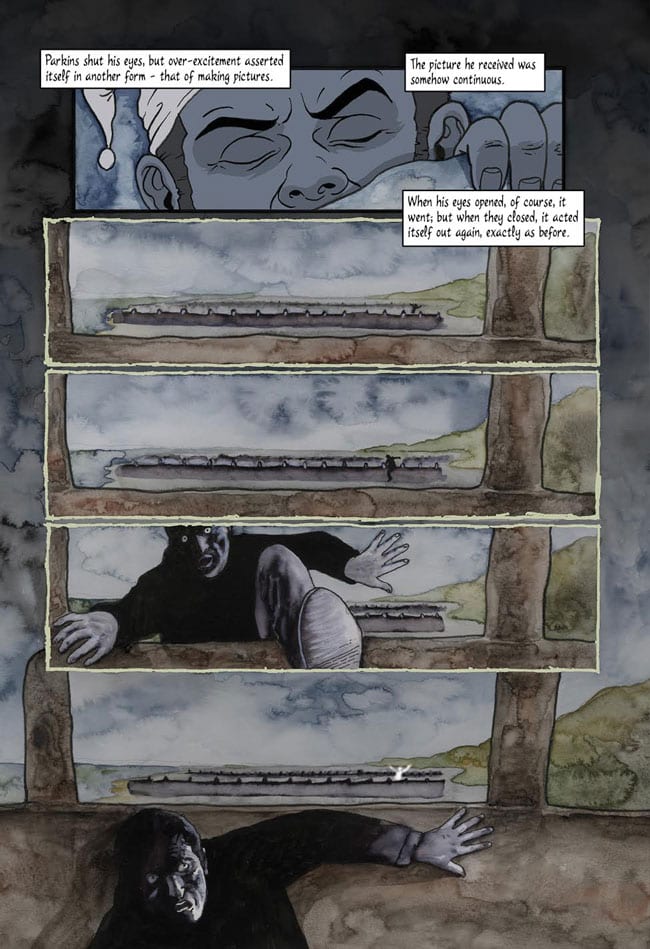

In contrast, Parkins, the protagonist of "Oh, Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad," has no idea of the danger he's courting by digging around in an old Templar Knights burial ground. But we readers see what’s right under his nose. We fear for him as he continually ignores the warning signs that he has awakened something inexplicable. Likewise, in "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas,” we know from the outset that Reverend Somerton’s search for a disgraced abbot’s treasure is a bad idea. (Come to think of it, as they are protagonists in M.R. James’ stories, we know Somerton, Parkins and Wraxall have big strikes against them right from the get go.)

Moore and Reppion have done a good job adapting the stories, trimming details and descriptions that would be extraneous in comics form, maintaining their essence without dumbing them down. But while the mostly digitally rendered art throughout the volume is smooth and professional, there's little that feels distinctive or exciting; you could mistake much of it for the work of any number of current artists, and its service to the stories is inconsistent. For example, the angular stylizations and gothic sensibilities of Abigail Larson in "Count Magnus" feel appropriate and help drive home the story's sense of enveloping doom (it also helps that she draws the supernatural figures only in silhouette, underlining their fleeting but threatening quality); but Meghan Hetrick's pastel watercolors for "The Treasure of Abbot Thomas" feel too warm and cheerful, defusing the tension. And her reveal of the lurking presence guarding the treasure is no match for James’ original narration, with its genuinely flesh-crawling, tactile horror. Al Davison's work on "Oh Whistle"—as with George Kambadais' for "Number 13"—works best in the all-out “scare sequences.” But overall, the stories feel more illustrated than interpreted—and the bland digital texts employed throughout don't help matters. I can't help wondering what James’ work (or that of Sheridan Le Fanu, another Victorian-era master of short-form horror fiction) might look like as rendered by, say, a Josh Simmons, a Dame Darcy, or an Emily Carroll. (I also think the great Mike Kaluta's evocative, spectral line would have been a natural for "Oh, Whistle.")

I enjoyed this volume. It's a fun October read, and it's good to see James' legacy continuing in this different form for a new era of ghost story fans. Here's hoping that Moore and Reppion, and SelfMadeHero, will continue to conjure more classic gothics into comics form, but mix it up a bit stylistically, with a less conservative, more go-for-broke approach.