Gazeta and Mome 19 were my favorite anthologies of 2010. What they have in common is a strong editorial hand that creates a unique aesthetic experience based not only on the specific stories selected for the book but also on the way the stories have been sequenced. That issue of Mome is the culmination of a lot of trial and error on the part of editor Eric Reynolds, resulting in a book that sees him trusting his instincts to create the sort of anthology that fully represents his own tastes as a reader. Gazeta, on the other hand, is a whole other kind of beast, one with different and frequently competing goals. Despite breaking a number of rules that I look to when judging an anthology's merit, it nonetheless hangs together in remarkable fashion.

Let's unpack the book's stated and unstated goals. The book's tag line is "Comics from Belgrade to Bangkok," and its editorial staff notes that "when we saw the following comics we loved them, and we thought you might love them, too." In other words, Gazeta is a survey anthology. International anthologies aren't especially unusual; the Kus and Stripburger series are good examples of this sort of thing, though some of the countries represented here—such as Cuba and Portugal—aren't familiar bastions of cartooning. In terms of unstated goals, it seems clear that the editors are interested in balancing different kinds of narrative flow while incorporating the work of multimedia artists. It's telling that in the credits section, the editors go out of their way to point out the other artistic and/or intellectual interests of the contributors. The pieces range from the traditional (if lyrical) cartooning of Dylan Horrocks and the immersive work of Ron Regé Jr to the dense, impenetrable pages of Aleksandar Opacic and the fine art work of Belkis Ayon. A third of the book's contributors are women.

It's that range of styles and their arrangement that makes it work, which is a tribute to its editors, Maria Sputnik and Lisa Mangum. Curating a best-of or survey anthology provides editors with an opportunity to reshape the works they select, in the sense that each piece will comment on those surrounding it by providing a new context. The best example of this is the Ivan Brunetti-edited Anthology of Graphic Fiction, which began with short-form gag works and moved steadily through Brunetti's curriculum as a teacher, with each successive work subtly building on an aspect of the previous story so that the observant reader could see how two separate cartoonists came up with different solutions to similar problems. Careful curating creates a greater whole, despite the fact that virtually every piece in the anthology is an excerpt from a larger work.

The editors get around that potential shortcoming through not only their aforementioned careful screening, but also via an uncanny sense of how much to excerpt, and it doesn't hurt that few of the stories are conventional narratives. As such, the reader doesn't feel dropped into or yanked out of a larger story, and can be allowed to immerse herself in the aesthetic of each artist. That's not to say that this anthology is a breezy read. Indeed, many of the stories here demand a lot of work and commitment on the part of the reader. Not every story necessarily rewards the reader, either, but the job of a great anthology is to challenge a reader as much as provide entertainment or an interesting aesthetic experience. That's why Kramers Ergot and Non are both revered and viewed with frustration at the same time: the editors took risks by including work that barely qualified as comics.

Let's go through the book story by story, and unpack the aesthetic style of each, along with how they fit in. Gazeta's table of contents adapts an astrological map across two pages, incorporating the obvious theme of worldwide travel with the slightly more esoteric idea of comics-as-maps, or as Dylan Horrocks would say, something that reveals the "geography of time" as opposed to the geography of space. The first story, André Lemos's "Repercussion", seems to be an excerpt from a longer story. Visually, the smudged art favored by the Portugese artist is out of Blutch's playbook. It starts the book off on a perhaps too on-the-nose note, as—clearly inspired by Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness—it's about a journey to meet an important man at the end of a river. Of course, the story takes a surreal turn when this Kurtz turns out to be an aggregate of intelligent mollusks. That bit of weirdness is a nice signal to readers that we aren't going to get a cliched "journey around the world" theme repeated ad nauseum throughout the book.

We go from blotches to smudges as Finland's Amanda Vähämäki contributes a story about a syndicated cartoonist struggling to find inspiration for his fox character under the weight of corporate editorial demands. Vähämäki, like Lemos, takes her story in an unexpected direction by steering it away from an inside-baseball approach to one where the cartoonist takes his hangover-ridden studio mate to get a drink. This is a story about inspiration striking in strange ways, mixed with almost viscerally-rendered sweat and puke.

After reading two stories whose art depends on distortion, it was a bit of a shock to be presented with the more traditional work of Dylan Horrocks. Using a simple line, he tells an achingly intimate story about a woman from the fictitious country of Cornucopia. The woman is resistant to lines of questioning as to where her country is located by her lover. For her, asking where it is an irrelevant question, because "all countries are imaginary." In comics terms, it's much like asking what a story is about; focusing on that detail can prevent one from understanding the emotional narrative of a story. It's a neat trick that Horrocks pulls off here, because there is no plot other than the exploration of the emotional arc between two characters, and yet the story has a satisfying beginning and ending.

Aleksandar Opacic's story is the only real roadblock I encountered in this book, and it's no coincidence that it was sequenced directly after the beautiful simplicity of Horrocks. Opacic's work is scratchy, opaque, and difficult to engage, the kind of comic in which my eye falls off the page because the denseness of detail makes it hard to follow or latch on to. In this case, the excerpted nature of the piece doesn't help matters any. On the other hand, the prints of Cuban-born Belkis Ayon are fascinating and boldly distinctive. Ayon's prints relate a story told by an Afro-Cuban secret religious fraternity, in a visually striking manner reminiscent of the sequential images of the Catholic Stations of the Cross. Like that of many of the other artists featured here, her use of black and white to create contrasts is especially bold and simple. The inclusion of her work is an inspired move, folding in an artist who was a rising star in the art world before her death, because it is a perfect fit within the context of the other lyrical and elliptical works in this volume.

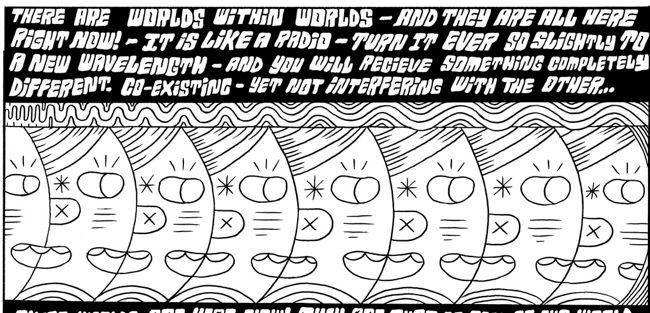

The book turns again from complex to simple visuals with Malaysian artist Sam Seen, whose lumpy figures and their travails remind me a little of old Fort Thunder comics. These silent, enigmatic images precede the more expressionistic but naturalistic work of Italian cartoonist Maurizio Ribichini. His loose line, use of shading, and focus on tales of youth are reminiscent of Gipi, though not nearly as accomplished or profound. The next three stories show different sides of utopias and dystopias. Nora Krug's strip illustrating text from a couple of "Rapture readiness" websites is hilarious in its execution, with the dull absurdity of the text offering up a feast of fun images to luxuriate in. Ron Regé Jr's explication of "affectional alchemy" is a bit of metaphysical gobbledygook, but the earnestness of his presentation as expressed through his beautiful, immersive art provides a forceful thrust for the disparate but related ideas he explores. Essentially, he argues for the power of imagination and love as transformative, creative forces. There's a brightness in this excerpt that's almost blinding when compared to the darker (both literally and metaphorically) pieces in the anthology.

That's especially true when one compares Regé's entry to the excerpt from Dunja Jankovic's Habitat. Here, Jankovic's character is living in a personal hell of nightmare logic, swirling and dizzying images, and an extreme detachment from self. Jankovic uses an almost vibratory line, smudges, collage, and grotesque figure work to express an experience that goes beyond despair and straight into absurdity. In many ways, this story provides the emotional climax of the anthology—Edmond Baudoin's follow-up, a naturalistic relationship tale, acts as a sort of sequential palate cleanser.

The arc of stories in Gazeta start by exploring different kinds of journeys, move into rituals and ceremonies, examine spiritual and emotional states of being and conclude by focusing on time and place. Lemos's "Solidesque" is about how a particular mountain carries particular meanings to its community before it was torn down. Croatian cartoonist Igor Hofbauer's "Nail Story" is somewhere between EC horror comics and Eamon Espey in its lurid and enigmatic imagery; it's the only story in the book that uses the color red. Finally, Vähämäki's second story is very much about the end of a journey, and finding unexpected magic and a sense of contentment in one's surroundings. For a book with so many harrowing images, choosing this story to close it out feels like the editors trying to comfort and reassure the reader after an occasionally difficult voyage. It's not an unwelcome send-off for an anthology that wisely doesn't outstay its welcome at just 124 pages.