Murder mysteries are defined by their central, structuring absences. A hole occupies the space where a life once lived. That hole can never be filled. But through an investigation of the facts, an uncovering of the truth, and a pursuit and capture of the killer, we can define and discover the shape of the hole to a degree of accuracy sufficient to put a cover on it, so that the still-living may proceed past it once more.

Gast, a graphic novel of exquisite and accomplished empathy and restraint by alternative-comics veteran Carol Swain, tells a story centered on a hole far harder to close up than most. It proceeds with the methods and mechanics of investigation and discovery. The scene of the crime is visited. The victim's routine is examined. The friends and acquaintances of victim and suspect alike are questioned. Evidence is recovered and cataloged: a discarded make-up bag, a shell casing, a stain on the bedroom wall. Means, motive, and opportunity are all established.

But there is no crime, because killer and victim are one and the same. There is no pursuit, no arrest, no trial, no conviction, because there can't be. We don't so much as see the dead person once -- not as a corpse, not in a flashback, not in a photograph. All we have is what is learned by a quiet, curious eleven-year-old girl, Helen, a lover of nature and long walks who must piece together even the most basic of facts about the deceased. At first we don't even know the deceased is a person: Helen is simply told of a "rare bird" who killed himself nearby, and as a Londoner newly arrived in the rural region of Wales where the story is set and unfamiliar with the antiquated expression, she starts her search looking for an actual bird. Like the pages of the ever-present journals, Helen starts with a completely blank slate. Over the course of many long wordless walks and quiet conversations with both her human and, mysteriously, animal neighbors, she slowly fills the tabula rasa with discoveries: suicide, gender dysphoria, the allure and peril of solitude, and the life and death cycle of this farming community and its inhabitants. She learns that most adult of lessons: We each of us have roles we play in the lives of others, shapes we take in their worlds—shapes that can be integral to those lives' landscape yet still not save us.

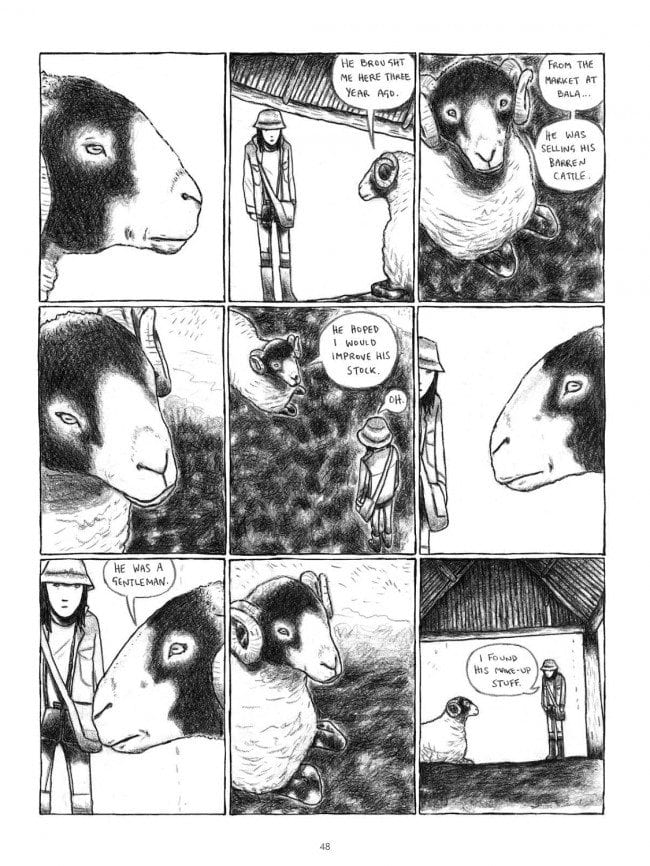

Gast follows Helen's investigation of the suicide of Emrys Bowen, a reclusive neighboring farmer best known to the locals for wearing women's make-up and dyeing his hair in bright colors. Emrys's neighbors, friendly acquaintances, and farm animals all use male pronouns and suffixes when referring to the farmer, so this review will as well; it's unclear if Emrys identified as male or female, and indeed this is the idea that animates the book's title, the Welsh word for a female dog. "Not sure if he was a cock or a hen," his dogs tell Helen during the earliest of their many magic-realist conversations with her regarding their late master, "a gi or a gast. He was a rare thing, though. Oh yes..." Helen recognizes the make-up bag among his discarded possessions easily enough, and contextualizes it just as easily.

The shotgun shell is harder for her, even after she learns what the strange cylinder really is. "He shot himself?" she asks the dogs. "Why?" "Quicker than hanging," they begin, explaining the inferiority of other methods. "No," Helen interrupts. "I mean why did he want to be dead?" They don't know, but suggests she talk to the tup, the ram in Emrys's flock. His insight is unsettling. The tup tells Helen that Emrys used the dye rubbed on rams so that they mark potentially pregnant ewes when mounting them to color his own hair. "He unsettled people with the way he looked. So he kept himself apart from them." "But Emrys made himself look that way, didn't he?" Helen asks. "Yes," the tup replies. "Some creatures mark themselves out as poisonous to avoid becoming prey." "Was he poisonous?" "No." And after a pause implied by word balloon placement and a row shift within Swain's nine-panel grid: "You humans are the saddest of animals."

Emrys, it seems, was undone by depression stemming from needing to be who he was, but living in a world where that was never quite enough. The only person to attend his burial, besides Helen, was his Avon lady, to whom he lied that his purchases were for his long-gone sister. His other closest acquaintance is the waitress at the restaurant in England he would take the bus to for lunch every day, a woman who thought he was a great customer and a kind soul but who had a grand total of one conversation with him in all his years of coming there. Emrys's family farm was failing: He sold off his cattle, and the tup he purchased to improve his stock has developed foot rot. "Did you know that a farm animal unable to get to its feet is doomed?" the tup, still standing (for now) tells Helen. The implication for the farm and the farmer, too, is clear.

Later, Helen encounters the tup in a special pen at a nearby livestock market. He's now a Judas sheep, he tells her; his job is to make other sheep comfortable by his presence so that they will be calm when sold and shipped away. "How's your foot?" Helen asks him after learning about his new gig. "Much much better," he says, before lowering his head and avoiding her eyes over the course of the next two silent panels. In the third panel, Swain violates the 180-degree rule, reversing the characters as Helen tells the tup she visited the dogs the day before -- visual shorthand for changing the subject. Helen has already learned much about how little good making the best of your situation and holding back hurt can do. No need to belabor it now.

Emrys's story is sad, but also sensitive. It must be handled with empathy rather than pity; it must be clear that his attempts to make himself more of what he was were neither a source nor a symptom of the sickness that claimed his life. Here is Swain's subtle masterstroke: She conveys this by making Helen's journey of discovery into Emrys's life and death just one layered band in a lattice of similar journeys and discoveries.

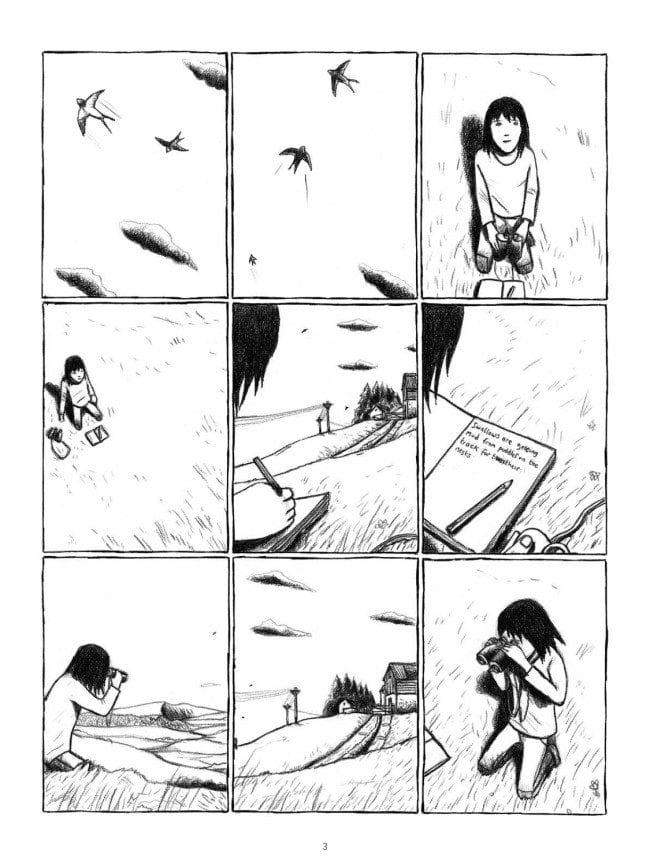

Some of those journeys are quite literal: Swain spends panel after panel, page after page for stretches at a time, depicting the villages, farms, towns, and countryside as Helen walks and rides through them. Her soft grey pencils are all but absorbent of the eye, creating a sensation of immersion. Like the similarly peripatetic cartoonist Ben Katchor, she draws from, and at, unusual angles, beckoning the eye to travel across the story-world's space to unusual nooks and crannies, dirty floors and empty skies. Her signature device is a perspective on Helen's travels that seems to have us hovering about five feet ahead and ten feet above the girl; the novelty of the point of view reinforces the act of walking as an act of traversing, describing, measuring the space walked.

At the same time, Helen is learning about more than Emrys. She's learning about the place where she now lives. She's drawing the animals she encounters, the birds she sees, writing about their habits and habitats. She's writing down all the new Welsh words she's learning from the two-legged and four-legged residents alike. She's getting an education in how farms work, how animals live, eat, mate, get sold, get sick. And quietly but importantly, she's learning how to live with herself and her environment in a place very different from her old home in London, left behind after an implied upheaval that feels woven deeply into her independence, her reserve, her calmly instinctive acceptance of the new.

All these journeys -- visual, factual, emotional -- are congruent and coterminous with all she learns about Emrys. And since all those journeys are good for her to have made, it follows that Emrys is a good person to know, to like, to understand. There will be no saving him, no filling the hole his absence leaves behind. That's a great tragedy for others, and a total tragedy for Emrys, whose existence and experiences matter most in and of themselves. But Helen's world is now shaped by his outline, an outline she painstakingly drew herself. For that, it's a better, truer world. And the shape of Emrys, which cost him so much to maintain, will not be erased.