It often seems unfair that an artist’s year(s)-long labour can be read in a disproportionally short span of time. I cannot say how long or short artistic appreciation should take, but I can say that when Jeff Lemire is the storyteller, even the smallest amount of time spent reading his creator-owned work leaves the reader with a lasting emotional impact. While the rough style of his artistry may not appeal to some, the almost painfully honest quality of his line perfectly complements the poignant nature of his original graphic novels. Frogcatchers, Lemire’s latest graphic narrative with Gallery 13, pulls together similar considerations found throughout his other original graphic novels such as Essex County, Lost Dogs, The Underwater Welder, and Roughneck. Like these prior works, Frogcatchers reflects upon life, loss, change, letting go, regret, and the awful truth of the human condition: the ephemerality of life. While most of the aforementioned works focus on the fraught nature of various relationships – parent/child, siblings, lovers, friends, or foes – this quiet little tale focuses on the complicated relationship one has with themselves. In the simplest of ways, Frogcatchers asks: Who are we? Are we a past, present, or future versions of ourselves? Are we some sort of combination that surpasses any of these? What part of our inner-selves guides us onwards?

I describe Frogcatchers as a ‘quiet’ little tale because the first quarter of Lemire’s work is silent, pulling the reader through memory, dream, reality, and the unconscious with nothing but the soundscape of creaking, splashing, and beeping for company. The decision to tell so much of the introductory portion of the work in silence adds to the spatial and temporal confusion between the conscious and unconscious realm, between past, present, future, real, or imagined moments. The reader, like the character, remains fluid between these states, unhinged from any markers that might bring stability or certainty. Lacking verbal specificity allows the mystery of the unnamed protagonist to become the mystery of the self and the universal journey one takes towards self-understanding.

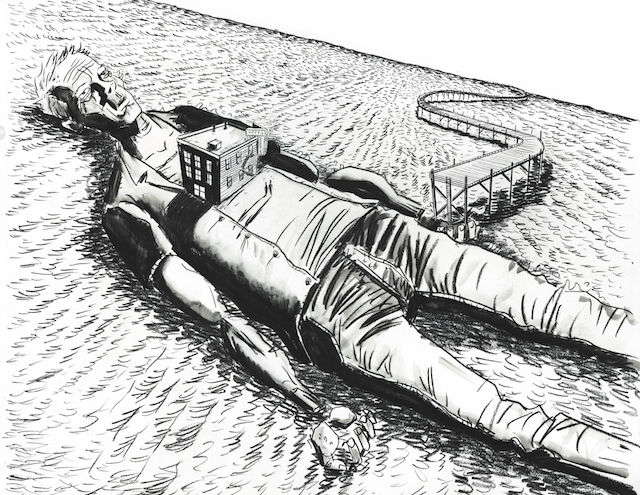

Lemire’s tale opens with a small figure hunched within a tunnel at the center of a double-page spread. The landscape beyond is empty and lush, quiet and pastoral, perhaps a young boy’s personal utopia. This image immerses the reader into the protagonist’s imagination from the outset. Much depends on the unobserved, unimportant space under the bridge, where the creek passes on its course unnoticed by those traveling along the main road above. But as Lemire draws the reader into the scene, they are compelled to pause and take notice that such a creek, like the flow of time, is teeming with life and possibility.

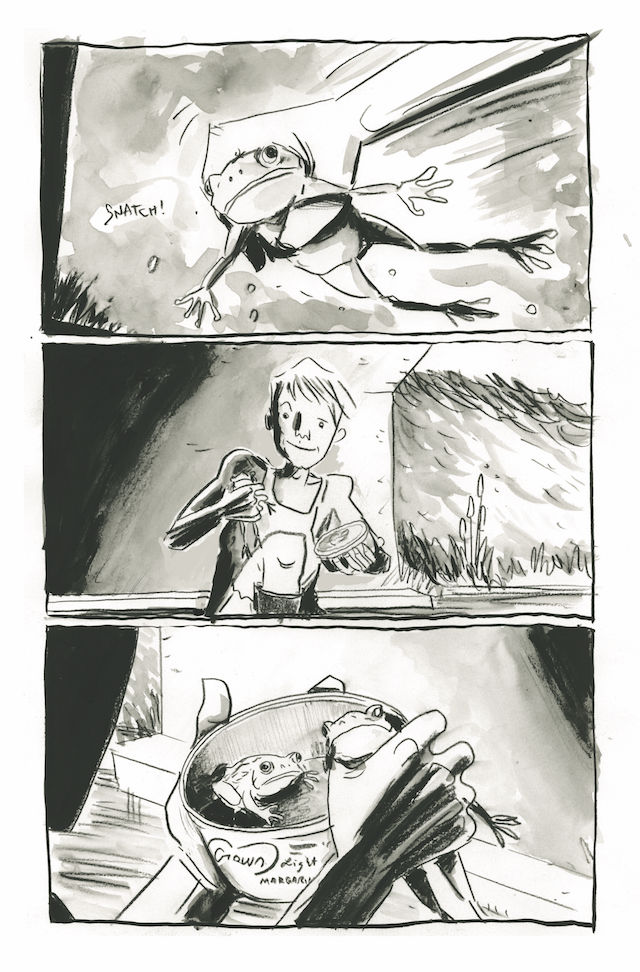

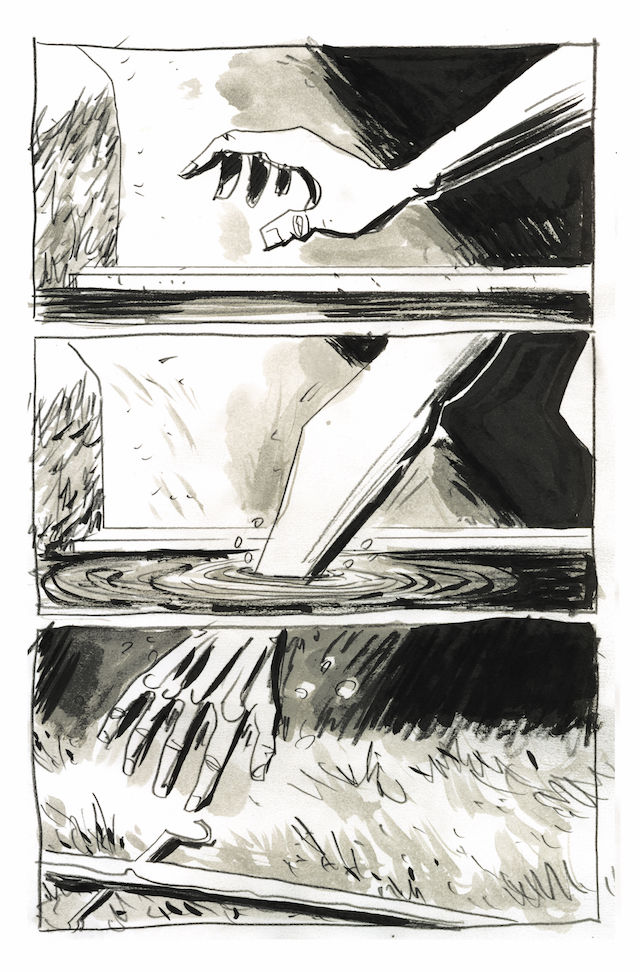

Lemire pushes the narrative focus forward from this establishing image to demonstrate the immensity that can encompass a single moment. Deep within the underpass tunnel a boy and a frog stare at one another in shot-reverse-shot. Lemire’s visual metaphor of “frog-catching” suggests that sometimes, if you’re quick and lucky, you can catch hold of the fleeting moments that define a lifetime. However, Lemire’s composition suggests that such moments are not everlasting, opportunities have a life of their own, existing in motion all around us. As the episode between boy and frog repeats itself in the subsequent panels, opportunity eludes him. Later in the tale, those opportunities – missed or captured – take demonic form as the Frog King’s agents, haunting the character’s psyche. Through such narrative repetitions and transformational visual metaphors, the story suggests that an entire life can be similarly defined through unassuming moments of gained or lost opportunities. The second of these early shot-reverse-shots between boy and frog visually give way to a deeper self-examination. The boy, gazing after the escaped frog, notices his reflection upon the surface’s water and must reach underneath that reflective surface to discover the potential that lies within him.

Lemire pushes the narrative focus forward from this establishing image to demonstrate the immensity that can encompass a single moment. Deep within the underpass tunnel a boy and a frog stare at one another in shot-reverse-shot. Lemire’s visual metaphor of “frog-catching” suggests that sometimes, if you’re quick and lucky, you can catch hold of the fleeting moments that define a lifetime. However, Lemire’s composition suggests that such moments are not everlasting, opportunities have a life of their own, existing in motion all around us. As the episode between boy and frog repeats itself in the subsequent panels, opportunity eludes him. Later in the tale, those opportunities – missed or captured – take demonic form as the Frog King’s agents, haunting the character’s psyche. Through such narrative repetitions and transformational visual metaphors, the story suggests that an entire life can be similarly defined through unassuming moments of gained or lost opportunities. The second of these early shot-reverse-shots between boy and frog visually give way to a deeper self-examination. The boy, gazing after the escaped frog, notices his reflection upon the surface’s water and must reach underneath that reflective surface to discover the potential that lies within him.

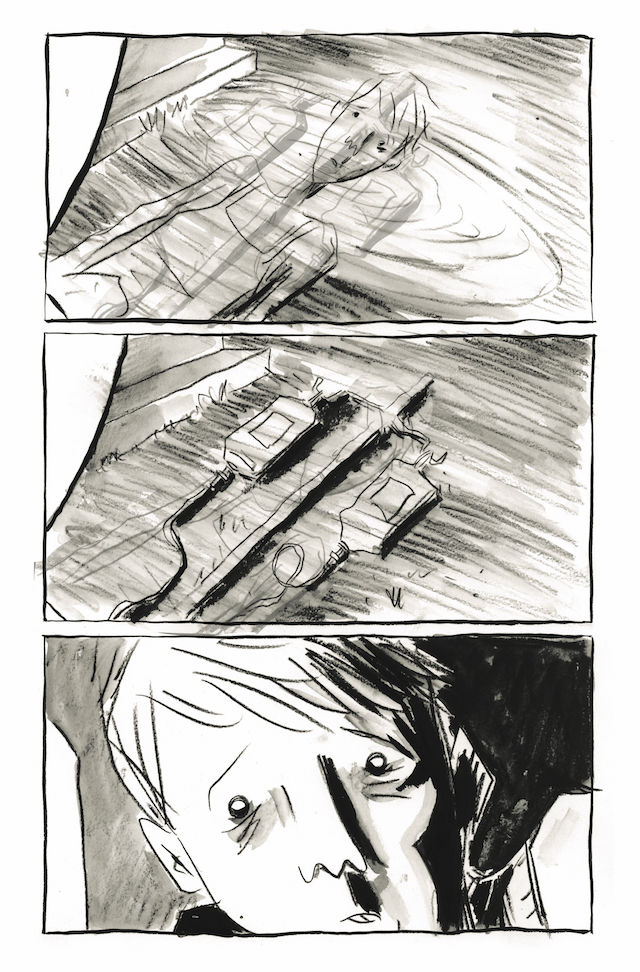

Though some may criticize Lemire’s rough hewn comics line, it is this coarse quality that bolsters his thematic approach to storytelling. The rough quality of Lemire’s line permits a thematic fluidity between states of consciousness, temporality, and even visual objects, as precisely rendered objects and characters would be too visually defined to transform themselves into other shapes, times, states, and ideas. Furthermore, the dreamlike quality of the storyworld defies specificity much like dreams provide only enough information to describe the dreamworld and its events. In this way, Lemire’s fluid artistic style plays with the very visual properties that might define objects in time and space. Manipulating contours, light and shadows, Lemire stretches and redefines the boundaries of the visualized object, turning fingers into ribs, underwater environments into x-rays, and bones into a man’s face. The slow artistic transformation that coaxes one image to emerge from another further suggests the cyclical and undivided nature of the self at the heart of Lemire’s story: external properties become internalized and internalized properties become externalized as a matter of course. Lemire’s fluid visualization suggests that our self-definition endlessly relies on this inseparable cycle. The only certainty of this cycle is its process of continual transformation. In Frogcatchers, a few haphazard changes in brushstrokes is all it takes to become something completely unrecognizable, something new, something other than what you were or will become.

Though some may criticize Lemire’s rough hewn comics line, it is this coarse quality that bolsters his thematic approach to storytelling. The rough quality of Lemire’s line permits a thematic fluidity between states of consciousness, temporality, and even visual objects, as precisely rendered objects and characters would be too visually defined to transform themselves into other shapes, times, states, and ideas. Furthermore, the dreamlike quality of the storyworld defies specificity much like dreams provide only enough information to describe the dreamworld and its events. In this way, Lemire’s fluid artistic style plays with the very visual properties that might define objects in time and space. Manipulating contours, light and shadows, Lemire stretches and redefines the boundaries of the visualized object, turning fingers into ribs, underwater environments into x-rays, and bones into a man’s face. The slow artistic transformation that coaxes one image to emerge from another further suggests the cyclical and undivided nature of the self at the heart of Lemire’s story: external properties become internalized and internalized properties become externalized as a matter of course. Lemire’s fluid visualization suggests that our self-definition endlessly relies on this inseparable cycle. The only certainty of this cycle is its process of continual transformation. In Frogcatchers, a few haphazard changes in brushstrokes is all it takes to become something completely unrecognizable, something new, something other than what you were or will become.

Lemire’s artistic fluidity also extends to other compositional techniques such as his use of framing. Like his visual style, Lemire’s structural technique belies instability, calling a sort of meta-awareness to the ideological structuring with which we surround our life’s story. Lemire uses panels to describe portals between states of consciousness, states of being, temporal states, and invisible boundaries that can be traversed. By controlling the story’s visual framing, Lemire controls the reader’s perspective into and movement through the storyworld. For example, Lemire’s recurrent play with shot-reverse-shot throughout the narrative continually turns the tables on the reader’s perspective of whether the present moment of the story is told through dream, waking, memory, or present reality. As soon as the reader becomes familiar with the established perspective, the perspective changes once again, shifting from an external perspective of the storyworld to the internal perspective of the character. This relentless perceptual shifting creates deepening states of confusion for both the reader and the protagonist. These perceptual transformations, which continually destabilize the storyworld and the characters within it, are masterfully controlled through the narrative’s framing and position the visual narrative to metaphorically operate like the current established in the story’s early symbolic images.

Lemire’s artistic fluidity also extends to other compositional techniques such as his use of framing. Like his visual style, Lemire’s structural technique belies instability, calling a sort of meta-awareness to the ideological structuring with which we surround our life’s story. Lemire uses panels to describe portals between states of consciousness, states of being, temporal states, and invisible boundaries that can be traversed. By controlling the story’s visual framing, Lemire controls the reader’s perspective into and movement through the storyworld. For example, Lemire’s recurrent play with shot-reverse-shot throughout the narrative continually turns the tables on the reader’s perspective of whether the present moment of the story is told through dream, waking, memory, or present reality. As soon as the reader becomes familiar with the established perspective, the perspective changes once again, shifting from an external perspective of the storyworld to the internal perspective of the character. This relentless perceptual shifting creates deepening states of confusion for both the reader and the protagonist. These perceptual transformations, which continually destabilize the storyworld and the characters within it, are masterfully controlled through the narrative’s framing and position the visual narrative to metaphorically operate like the current established in the story’s early symbolic images.

The narrative’s circular ending also serves to emphasize the infinity encompassed within the single moment. The narrative current that sweeps the reader along the tale finally returns them to its opening scene – much like a creek’s water changes in its ceaseless flow, but somehow remains the same stream. So too operates the stream of consciousness that encompasses the protagonist’s choices, regrets, and memories. These both live inside of him as he simultaneously lives within them. Lemire’s few double-page spreads remind us of this human condition by situating the location of the story within the self from the outset. The difficulty lies in achieving the correct perspective to recognize that there are multiple selves within the self to be explored, understood, lived through, and supported by. The challenge may lie in trying to coexist with all of these selves and do right by each of them.

Lemire’s Frogcatchers, is a visually and narratively rich tale that suggests the key to navigating life and the self is to remain amphibious, to see under the surface of things, to grasp at opportunities, and to remain open to the constant change found within life’s current. That Lemire is able to unfold the mysteries of the human condition so fully, so seemingly simply, and so impactfully in a scant one hundred pages is the magic of his particular brand of visual storytelling. Perhaps it is less that Lemire tells a story and more that he articulates the invisible currents surrounding our lives through story. Perhaps some stories seem to unfold so quickly in their narrative current because they are universal and timeless. Perhaps – much like a current – this is why it is so difficult to remain unmoved by such skillful and emotional storytelling as Lemire’s.

Lemire’s Frogcatchers, is a visually and narratively rich tale that suggests the key to navigating life and the self is to remain amphibious, to see under the surface of things, to grasp at opportunities, and to remain open to the constant change found within life’s current. That Lemire is able to unfold the mysteries of the human condition so fully, so seemingly simply, and so impactfully in a scant one hundred pages is the magic of his particular brand of visual storytelling. Perhaps it is less that Lemire tells a story and more that he articulates the invisible currents surrounding our lives through story. Perhaps some stories seem to unfold so quickly in their narrative current because they are universal and timeless. Perhaps – much like a current – this is why it is so difficult to remain unmoved by such skillful and emotional storytelling as Lemire’s.