I had originally intended to take a quick look at this first issue of Lance Ward’s Flop Sweat series just to get a feel for what it was about so I could decide where to place it in my (ever expanding) to-be-read pile. But before I knew it, I was hooked and I finished it in a single thirty-minute sitting.

Ward relates this woeful autobiographical tale with a directness and honesty that’s downright arresting. Though none of the story is pretty, he sprinkles in just enough dashes of hope, humor, and a latent sense of self-awareness that ameliorates some of the bleakness. With at least five more issues to come, there’s the good possibility that we’ll see him suffering through a lot more pain and trauma. But there’s also the prospect of seeing him overcome at least some of his difficulties. After all, he wrote it all down, drew it, and got it published, right? So he’s doing at least little better, right?

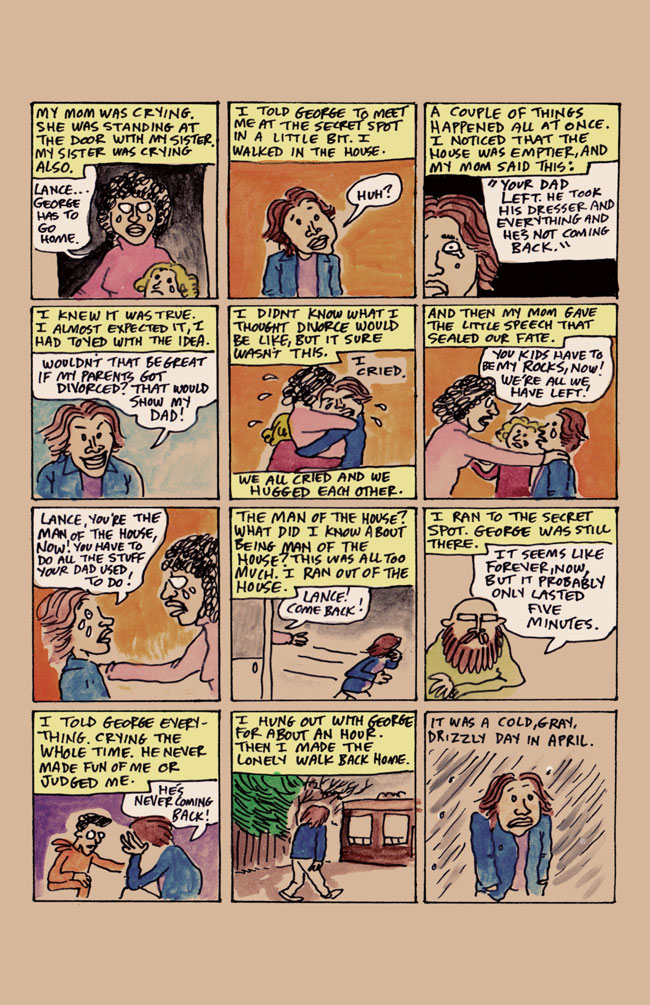

Ward begins his narrative in spring of 1980, when he was eleven years old and living with his parents and younger sister in Forest Lake, Minnesota, a small city about twenty-five miles north of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul. These are the final days of his family’s relative stability before Ward’s dad abruptly walks out on the family. He describes his father as a type-A sports enthusiast, and himself as the polar opposite. “My father was very disappointed with his family,” Ward says. “I could see it on his face when he looked at me. When he spoke to me.” His mother, while loving and supportive, quickly spirals downward after his dad’s exit.

Ward, already a sensitive, budding artist type, has a close friend named George who is supportive simply by being a good listener. George’s family is Pentecostal Christian and Ward visits a church service with him at one point. Though he is thoroughly turned off by the parishioners “jumping up out of nowhere and yelling,” Ward’s friendship with George remains intact. It is clear that even at a young age he has already established an affinity with outsiders.

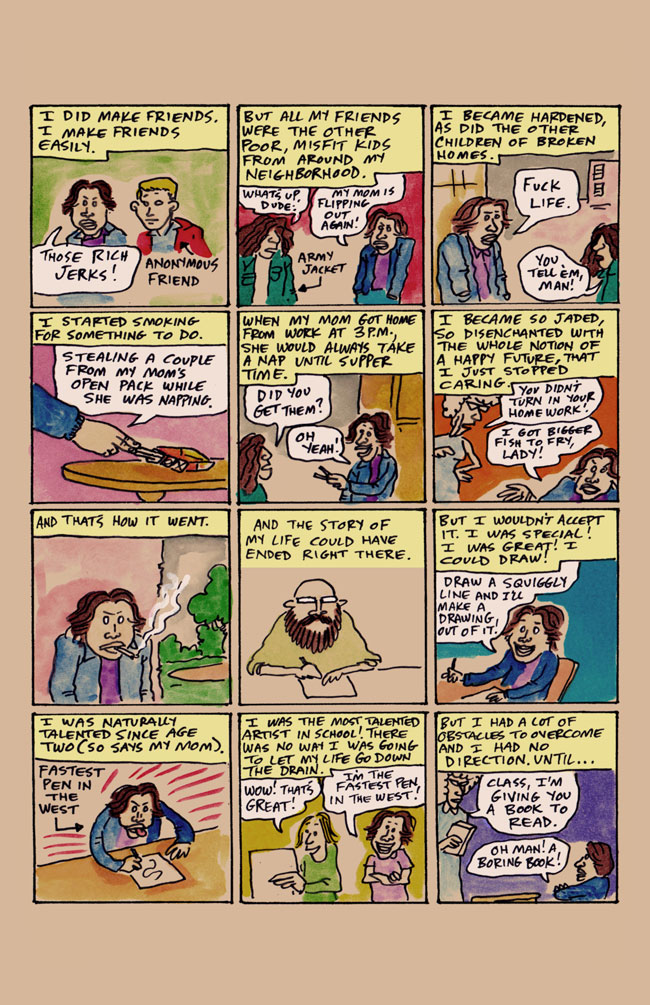

Things get worse at home. Ward notes that the family was already poor, but with their dad gone “now we really felt it!” Meanwhile, his mother becomes a stranger to him: “She ceased to be the woman I grew up with and became someone angry, bitter, and frightening.” With money so scarce, she buys the kids the cheapest clothes she can get, including off-brand shoes. Ward is then subjected to cruel bullying by some of his peers; he gets the nickname “K-Mart Shoes.”

Though Ward continues to have travails at home and at school, he experiences some intermittent bright spots amidst the gloom, like finding joy in riding an old bike his dad left behind, getting cast in a school play, then discovering the pleasure of not only reading comics but then drawing his own and sharing them with a small group of his peers. These things afford him some solace. But just as everything starts to seem more hopeful, his mother takes up with a big, nasty, alcoholic ne’er-do-well named Jim, who goes out of his way to belittle and bully Ward. The rest of this issue focuses on Ward attempting to cope with all of this trauma, often by acting out and getting into trouble. It’s a sad and harrowing story—and this is only part one! But I was left wanting to read more.

Ward is a talented artist who creates and publishes comics in a variety of styles, including many that are much more polished than Flop Sweat (some of his work was even featured in the 2016 edition of Best American Comics). He explains Flop Sweat’s off-the-cuff aesthetic in a brief introduction: “I did it in a loose, scribbly style, as I was operating on pure recollection. I felt that had I penciled them first, I would have lost the essence of my raw memories.” I back this choice wholeheartedly; whatever the drawings lack in refinement is made up for in their immediacy and sincerity. There’s something about this approach to art that I have always found appealing, an anyone-can-do-this aesthetic that feels like an invitation to do just that. There are a few scattered panels where we can see Ward cramming the text into the panel, underscoring his resolve to communicate by every means necessary through this improvisation. And like certain other memoir cartoonists such as Tatiana Gill or Max Clotfelter, there’s a sense that Ward’s telling his story straight, with no adornments—less confessional than pure catharsis.

Ward is possessed of a forceful and uncompromising voice. Autobio and memoir comics fans, please take note.