The world revolves around labor. We keep being taught this lesson, but a century and a half after someone explained the fairly obvious fact that the only real division between people is that division between those who own capital and those who have nothing to sell but what their bodies and brains are capable of, it seems like we haven’t really learned it.

It’s a shame that stories like Fire on the Water – an exciting new graphic novel from veterans Scott MacGregor and Garry Dumm, the illustrator who did much of the early art on Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor – continue to need to be told. But our heroes are imaginary elites, chosen sons and daughters, and the products of privilege, and it usually takes a disaster to remind us that the people who actually keep things running day to day are far more worthy of our respect and far less likely to get it. (Any resemblance to this statement and current events is in no way coincidental.) It tells a strongly fictionalized story of a largely forgotten real-life disaster in MacGregor & Dunn’s beloved hometown of Cleveland, when a team of tunnelers were trapped in a gas-filled passage under Lake Erie over a century ago. Pushed into action by city fathers responding not to their perilous working conditions, but to the inconveniences of the wealthy, these men (some of them survivors of a nearly identical disaster ten years before) were forced to choose between putting their lives on the line and utter poverty for themselves and their families; then as now, that’s no choice at all.

It’s a story not many outside the region know about, but at the same time, it’s frustratingly familiar: the tunnels were dug in the first place to pump clean water into the city, an idea dreamed up by clever men laboring under the illusion that natural resources would last forever and were immune to depletion and pollution; and the incredibly hazardous conditions that existed in them were exacerbated by the greed and indifference of the wealthy, who considered their own comfort of supreme value and that of those who sacrificed themselves to provide it purely expendable. As always, the capitalists exploited racial, national, and class conflicts to keep the workers divided: hierarchies were set up between native whites and foreign immigrants, Protestant Germans and Dutch against Irish Catholics, and blacks against whites, which are illustrated starkly in the storytelling. (A very helpful and informative introduction by labor historian Paul Buhle provides much-needed background to the book.)

If the book has a hero – and to its credit, it avoids the obvious pitfall of making its story about exceptional and morally uncompromised heroes – it is Benjamin Beltran, an itinerant African-American inventor who has trouble selling a helmet he designed that allowed rescue workers to resist the dangers of smoke inhalation because no one wants to purchase or advertise a product made by a black man. Beltran isn’t a real person, but he’s based on the actual black inventor Garrett Morgan, whose life is described in a text addendum to the book. He’s a perfect example of how the stories of working-class struggles are always intersectional; the white workers were considered disposable because of their poverty, and Beltran’s life-saving device is considered worthless because few whites can credit a black man with having invented something so useful. Like the victims of the Erie tunnel disaster, Morgan was largely forgotten by a history written for the elevation of white elites.

If the book has a hero – and to its credit, it avoids the obvious pitfall of making its story about exceptional and morally uncompromised heroes – it is Benjamin Beltran, an itinerant African-American inventor who has trouble selling a helmet he designed that allowed rescue workers to resist the dangers of smoke inhalation because no one wants to purchase or advertise a product made by a black man. Beltran isn’t a real person, but he’s based on the actual black inventor Garrett Morgan, whose life is described in a text addendum to the book. He’s a perfect example of how the stories of working-class struggles are always intersectional; the white workers were considered disposable because of their poverty, and Beltran’s life-saving device is considered worthless because few whites can credit a black man with having invented something so useful. Like the victims of the Erie tunnel disaster, Morgan was largely forgotten by a history written for the elevation of white elites.

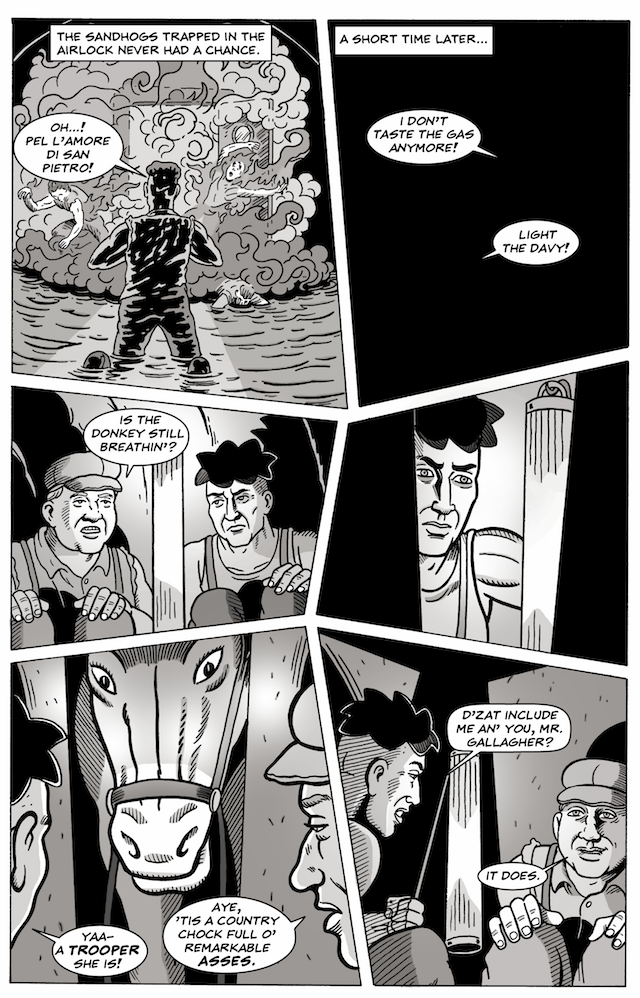

Beltran’s story is almost too good to be true, as are many such incidents in the book. (The fact that many of them are nonetheless accurate, like the brawl that broke out in the courtroom when the scandalous cover-up was brought to trial, do little to lessen their mythological qualities.) This is a book of legends, a book of divine interventions and prescient dreams and vengeful spirits. Fire on the Water is not an expressly political book, but it leaves readers to draw their own conclusions from the rather obvious evidence presented. It’s a simple and straightforward story plainly told, but it also wraps itself up in a legendarium, because there are otherwise precious few victories to be had in its narrative. MacGregor’s script does an excellent job of communicating the rough humor, the casual familiarity, and the crude combination of religiosity and earthiness that marks the workers who are its focus, and these are people who believe that miracles can happen, because what else is there to give them hope?

It is not a book without flaws, to be exceptionally kind. MacGregor does a good amount of narrative hand-holding, and there’s a lot of background to the story that he lets be told through some pretty awkward in-panel narration. The dialogue strives for verisimilitude, but despite this – or maybe because of it – it can sometimes come across as hokey. It is neither elegantly written nor beautifully drawn; Dumm’s art is more functional than it is lovely, though he does what he needs to do to communicate the story. Nothing in Fire on the Water elevates the medium to any place it hasn’t’ been before. But the pacing of the book is hatband-tight, and not a moment lags, not even in the occasional slapstick moment. There is a terrific sense of urgency in a story that is otherwise a foregone conclusion. It is not a book for sophisticates, but it does what so many historical graphic novels promise without delivering: it brings the story it wants to tell to vivid and sparking life.

It is not a book without flaws, to be exceptionally kind. MacGregor does a good amount of narrative hand-holding, and there’s a lot of background to the story that he lets be told through some pretty awkward in-panel narration. The dialogue strives for verisimilitude, but despite this – or maybe because of it – it can sometimes come across as hokey. It is neither elegantly written nor beautifully drawn; Dumm’s art is more functional than it is lovely, though he does what he needs to do to communicate the story. Nothing in Fire on the Water elevates the medium to any place it hasn’t’ been before. But the pacing of the book is hatband-tight, and not a moment lags, not even in the occasional slapstick moment. There is a terrific sense of urgency in a story that is otherwise a foregone conclusion. It is not a book for sophisticates, but it does what so many historical graphic novels promise without delivering: it brings the story it wants to tell to vivid and sparking life.

If there is one thing Fire on the Water does exceptionally well, it is illustrate how the brutalities of capitalism become more apparent and more violent the closer you get to the critical point where work is actually done. The bosses responsible – the city fathers who employ the sandhogs – are barely seen, though their corruption and avarice is eventually laid bare, and their decision to send men to their death while providing themselves with plausible deniability is, to them, an abstraction. But out on Whiskey Island, those men’s decisions are enforced by the fist and the club, and the bad decisions made at the bottom – whether it is agreeing to work in transparently unsafe conditions because passing up a paycheck means starvation for one’s children or taking bribes to pad your salary because a blood-soaked piece of the pie is better than no pie at all – are forgotten echoes of the whims of big men. The names of the victims will be forgotten while the wealth of the perpetrators still lingers in the fancy lakeside homes of Cleveland.