From the perspective of a reader of comics, the graphic novel is a mature aspect of the world of book publishing. But the larger literary world is hesitant to put unique and borderline work into the category of "comics." A recent example from Siglio Press; the “photo-novel” Eternal Friendship by French author Anouck Durand. Originally published in France as Amitié Éternelle, and translated by Elizabeth Zuba, Durand uses official and personal photographs from Albanian state photographers to create a story of friendship, politics, and totalitarian power.

The strange nature of this print object is apparent even at first glance. Eternal Friendship is a narrative work comprised primarily of photographs and text. But Eternal Friendship is not traditional photo comics or fumetti. There are no word balloons, no dialogue, none of the ephemera associated with the conventional conservative definition of comics. And this is apparent in the way that Siglio Press markets the book, as a “photo-novel,” a term that is as much a hedge as it is a recognition that Eternal Friendship does not easily fit in the lines we draw around narrative form. Still, despite Siglio Press’ hedging, Eternal Friendship is clearly a comic. It is a combination of image and text used to tell a story that only works with both parts intact.

Eternal Friendship is a fictionalized true story of two real men; Refik Veseli, an Albanian Muslim, and Mosha Mandil, a Yugoslavian Jewish photographer on the run from the Nazis. Veseli hides Mandil and his family at great personal risk, and Mandil teaches Veseli how to be a photographer. After the war, the two part ways, and Veseli uses his new skills to open his own portrait studio. As Albania closes its borders and digs deeper into Marxist-Leninism under the leadership of Enver Hoxha, Veseli becomes a state photographer. His friend Mosha lives and works as a photographer in Israel, and the two keep in contact. Durand starts the narrative of Eternal Friendship when Veseli is sent on a state-sponsored trip to Mao’s China. As a state photographer, he is sent to learn a special technique for creating color images from black and white film. But during this trip, he has the chance to send an uncensored letter to his friend Mandil; the risk that he’ll be caught and punished for that act hangs over the expedition throughout.

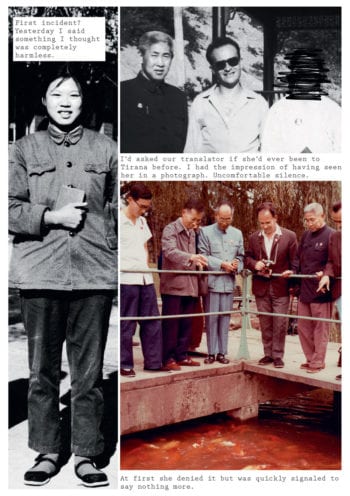

Eternal Friendship is a 100-page hardback with glossy photo paper, consisting mostly of reproductions of 20th century photographs and propaganda literature. It also includes real letters between Veseli and Mandil. These found materials form the visual background of the comic, while Durand constructs Veseli’s narrative out of text superimposed over these materials. Professional work, home photo albums, interviews, and letters give Durand the raw material with which to build a fictional inner monologue for Veseli, whose thoughts we read throughout Eternal Friendship. Using real world events and building fictional narratives within them is nothing new, but it seems Durand is more intent on creating a true-to-life monologue for Veseli.

Eternal Friendship is a 100-page hardback with glossy photo paper, consisting mostly of reproductions of 20th century photographs and propaganda literature. It also includes real letters between Veseli and Mandil. These found materials form the visual background of the comic, while Durand constructs Veseli’s narrative out of text superimposed over these materials. Professional work, home photo albums, interviews, and letters give Durand the raw material with which to build a fictional inner monologue for Veseli, whose thoughts we read throughout Eternal Friendship. Using real world events and building fictional narratives within them is nothing new, but it seems Durand is more intent on creating a true-to-life monologue for Veseli.

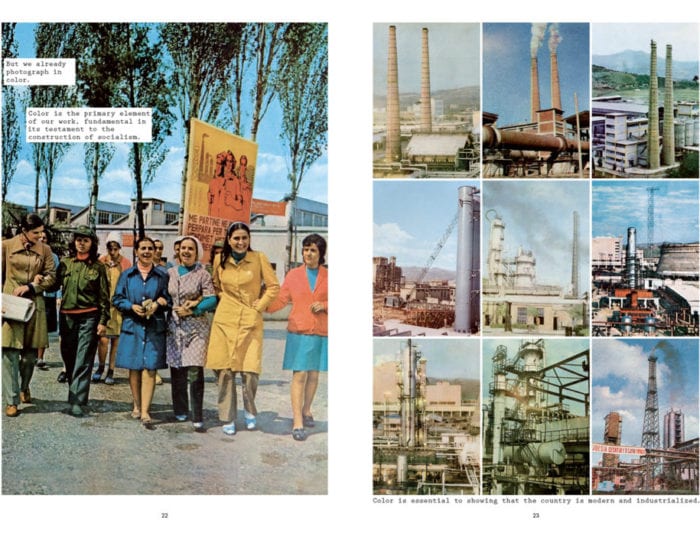

Throughout the work, Durand uses her page design to emphasize specific features of the photographs in use. The intentional manipulation of these materials along with Eternal Friendship’s narrative overlay is what changes a collection of photographs into the realm of comics. Early in the book, Durand uses a 3x3 grid to show a variety of Albanian propaganda photos; wheat fields, the bright red Albanian flag, the soldier-comrade, artillery, factories, and industry. The grid implies multitude; Durand uses them to reflect the propaganda machine’s emphasis on growth and strength. These images were necessary to create an image of a prosperous, powerful communist Albania, but Durand stages them in a way that makes these photos feel intrinsically false. Likewise, idyllic pictures of tourist sites in black and white are highlighted with red text, an ominous accent and a reminder of Chinese propaganda.

The link between Veseli’s thoughts and the images presented in Eternal Friendship is often tenuous, as though these found materials are the subconscious mind churning behind conscious thought. In a scene where Veseli ruminates about an upcoming personal visit with Mao, he is instructed by the ambassador what to do and say, and is reminded of China’s aid to Albania in the development of its industry. A factory’s smokestacks loom large in grayscale on the opposite page, phallic and domineering. The message is clear. State power is everything; obstruct it at your own risk.

What is striking in almost all of the pages of Eternal Friendship is the intention of Durand as an author. Working with photographs, letters, and other found materials is a purposeful constriction of the author’s ability to craft narrative. But the strength of Veseli’s relationship with Mandil and the toxicity of the propaganda state is crystal clear. It is Durand’s staging of these materials and the intentionality of her compositions that drive both the narrative of Veseli’s visit to China, and the critique of these totalitarian communist states.

Durand also uses these materials to explore life under totalitarian communist leadership, making clear the control the state had on the lives of Albanian citizens. Veseli talks about the stains (in Albanian, njollё) on his person for being unwilling to close his portrait studio. He is all too aware of how his relationship with Mosha Mandil and his njollё could lead to imprisonment and death. Albania, like China, sought to control all information in, around, and out of the country. Veseli was an important conduit of that information, and as such, was keenly at risk. We see that at-risk mindset revealed in Vesili’s clipped phrases and subtle hints. The small details build up, giving Eternal Friendship a sense of heightened tension throughout.

We see this tension flare up in the trip Veseli takes with the photographers to China - an offhand comment by Veseli leads to the removal of one of the Chinese delegation. The embassy warns them not to give away any state secrets. The all-seeing eye of comrade and state color much of narrative. The photos in Eternal Friendship, much of which were used for propaganda, feel sinister and dark, despite their bright colors. The photos from the China trip all seem touristy, but Veseli reveals the truth in a quick aside - all the sites for photographs have been selected. Even the photos of a tourist’s visit are used in a hunt for manufactured truth and control.

The historical context of Eternal Friendship is not just the real relationship between two men, but the real relationship between two communist states divorced from the USSR in the 1960s. Hoxha’s Albania and Mao’s China allied themselves in that time, sharing techniques for industrialization. But the truth of this “eternal friendship” is that it was fraught. Perhaps at the time it was politically expedient, but it was an eternal friendship that didn’t last. No better a place do we see that than in Durand’s narrative. Nominally, we know that Veseli and his team are in China to learn a color photography technique. But Albania’s photographers, who are using Kodak film imported from the West, never use China’s technique.

The disconnect between communist nations grew larger over time as the relationship between Albania and China soured. At the end of the strategic partnership between the two nations, Veseli and his companions destroyed or modified photos with Albanian leaders and Chinese leaders under direct order from the state. One specific image of Mao shaking the hand of Hoxha is scribbled out, Mao’s face obscured by marker, and we see these deletions and revisions throughout Eternal Friendship. Durand includes a striking image of Mao, a burned portrait. We learn in an afterword that the only reason some of the photos exist at all is because one of the photographers was imprisoned during the time where the order was given to destroy all photos that link Albania to China. His personal archives were not destroyed, even if his professional work was. In this way Eternal Friendship is a work of recovered memory - memory a communist state suppressed for ideological reasons, and which Durand has brought back to light.

And perhaps this is the reason that Eternal Friendship has to exist as a comic. It needs the art and work of Veseli and his colleagues to humanize their struggle and to place that struggle into a context which has been suppressed by the state. It is Durand’s curation of materials and formal experimentation that makes the narrative of Eternal Friendship so affecting. Ultimately it is the juxtaposition of the broken “eternal friendship” of Albania and China with the truly eternal friendship of Veseli and Mandil that makes Eternal Friendship work. These two men, different in so many ways, maintained regular correspondence despite the censorship of the Albanian government. This cord of friendship, forged in the fires of resistance to extremism, continued to bind them together, even though the risk to Veseli’s life was great. Durand’s telling of that story is essential reading.