It's difficult to keep up quality and continuity in an anthology that has an open call for submissions. It's doubly hard to do so when you have something of a gimmick as a theme. It takes an editor with a strong hand and clear vision to arrange something that coheres. Fortunately, the Elements series has such an editor in Taneka Stotts. In many respects, this anthology is an ideal survey of the current generation of genre comics artists mostly working on the web or for smaller publishers. The fact that the book was advertised as being entirely by creators of color worked to Stotts' advantage as an editor, because while not every story involves race or ethnicity directly, it is obvious that each story comes from a place that at least has some similar sensibilities. That gives each story a rich, personal set of interconnections that are far more powerful than the "Fire" theme; indeed, the most successful stories in the book blend both themes in clever ways.

The anthology is successful on a number of levels, but its surface aesthetics are one of the most significant. In a book with 23 different stories and a wide variety of visual approaches, Stotts cleverly uses a single spot color (red, for fire, of course) in a book that's otherwise black and white. Sometimes red is used with overwhelming force in the course of a story and other times there are simply wisps and hints of the color. This smart editorial decision gives each story a common but distinct visual language, unlike anthologies where every single story look the same, both in terms of subject matter and technique. That was one of the biggest problems I had with the old Flight anthology series.

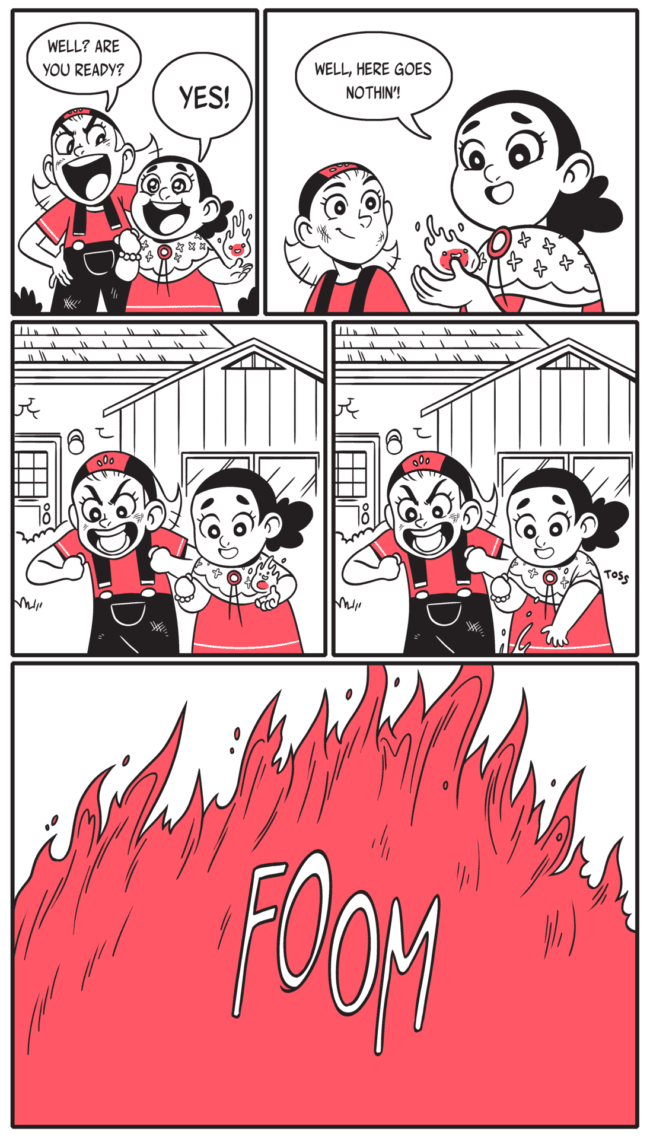

While some of the artists in the book work in animation, this anthology is also unlike Flight in that the focus is much more on the stories than the visuals. This is an anthology by cartoonists (some of whom happen to be animators), rather than an anthology by animators dabbling in cartooning. Elements: Fire has a nice rhythm thanks to its stories being around ten pages apiece, with some exceptions. Stotts follows some of the longer stories with two-pagers as a sort of aesthetic palate cleanser before transitioning back to more lengthy entries. Stotts arranges the stories such that no two that looked similar followed each other. For example, Kou Chen's slowly-paced, naturalistic story about two tribes merging in fire to survive is followed by the cartoony, frenetic story from Maddi Gonzalez about a young witch. The former story is notable for its gray wash and subtle use of reds until the very end, while the latter is pretty much drowning in red thanks to its young firestarters.

Love and acceptance are sub-themes running throughout the book, though they manifested in different ways. Sara DuVall's story finds its protagonist channeling magical power to bring back her beloved dead dog, and its ending is ambivalent. Myisha Haynes' story is a sweetly-drawn romance that veers into the old trope of not noticing the person who really loves you. It is certainly predictable, yet its execution and the fantasy trappings surrounding the plot are so charming that it didn't matter.

Even the slighter stories still have something to recommend them: Rashad Doucet's engaging, scribbly pencils in a story about flight; Marisa Han's character designs in a mythological origin story; Isuri Merenchi Hewage's ruined city and the way it feels so thoroughly lived-in; Chan Chau's sweeping splash pages depicting the goddess Pele; the wacky, wrestling-inspired energy and action of Orunmilla Williams; and the dramatic contrast of gray and red in Kiku Hughes in a story aimed at smashing old beliefs. Story after story has something to recommend to it, and even a long collection like this proves to be a remarkably smooth read. There aren't any points where the book dragged nor any sense of padding. Though this collection centers around science fiction and fantasy, the stories themselves are off-beat enough to prevent reader fatigue.

A few stories especially stand out. Der-Shing Helmer's "Pulse" is an interesting twist on the tradition of stories about scientific exploration, turning it into a metaphor for colonization. Her line is beautifully distorted, built on curves; and this is well-suited to a story about a scientist about to forcefully establish communications between humans and aliens composed of electrical impulses. It's a story about questioning one's assumptions and learning to have respect for methods that aren't your own. Stotts' "Pass The Fire" combines future dystopias with Greek mythology; in the future, "gods" have a stranglehold on information and most people have to do without. The protagonist's identity is kept secret until the end, which results in an extremely satisfying ending. Stotts really leans into the idea of the elemental quality of fire as that of knowledge--light, in addition to heat. Artist Mildred Louis establishes an appropriately gloomy, techno-noir setting before the final build-up of red.

Tristan J. Tarwater and Michelle Nguyen's "Under The Flamboyan" is remarkable for the denseness of its hatching juxtaposed against the lightness of the character design and the emotional intensity of the spot colors. It's a story about the price of knowledge whose ending avoids a couple of potential pitfalls and instead settles on a more ambiguous but still hopeful iteration. Jy Lang, Yasmin Liang, and Chan Chau's "A Burner Of Sins" is most notable for its mix of precise, clean-line art mixed with an almost ethereal use of red in a story about guilt, anger, regret, and the complexity of families. Its message reflects an emphasis on humanity being more important than the rules of rituals.

The best story in the anthology is Christna "Steenz" Stewart's "The Update". Her delightfully scribbly line is amplified by spot reds, creating an interesting balance between color and gray wash in each panel. Hair is the main recipient of that spot red, establishing an interesting panel-to-panel flow as we follow those small swathes of red across the page. Her character design is expressive, and reading facial expressions while tracking color creates a dynamic tension on each page that reveals as much about what's going on in the story as the narrative captions do. It's a story where everyone in the city is plugged into a seemingly benign neural network that keeps everyone running efficiently.

The narrator, Kime, thinks she sees two people disappear after one of the regular systemic updates, and her best friend shares a dream about running from people in suits. That this paranoid fantasy comes true isn't what's interesting about the story; instead, it's the way that Stewart implies how easy it is to be reprogrammed and assimilated. The paradox is that the very feature that appears to give each citizen freedom to express themselves (a device that records one's thoughts like a blog) is the same tool that allows the system to root out those whom might question it and thus make it less efficient. The cute, casual quality of her character designs and her drawing style makes the story even creepier, creating a disconnect between the story and its surface qualities.

Elements: Fire is not just an a snapshot of what quality fantasy/sci-fi comics look like today but is also a game-changer. This anthology series is going to have a substantial effect and influence on comics in the future, both because of Stotts' particular aesthetic as an editor but also because of her mission of inclusiveness. A future where fantasy stories are directly informed by each artist's personal experiences instead of relying on formula is one where genre stories will feel more authentic and lived in. That's especially true for an anthology featuring creators whose work and lives may have been marginalized at some point in their careers. For them, the escapist, utopian or dystopian aspects of genre fiction are more than just hackneyed and impersonal plot points; exploring those worlds from a new and more personal perspective will reinvigorate and revitalize genre comics.