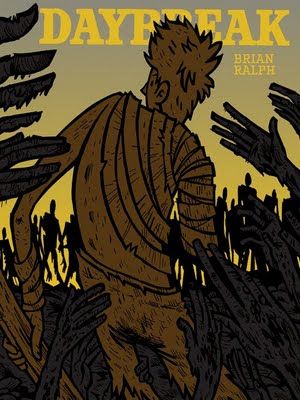

Brian Ralph's protestations -- and countless reviews and articles (several of them by me) -- notwithstanding, Daybreak is not the comics equivalent of a first-person shooter. While everything you see while reading Ralph's take on the zombie-apocalypse genre is shown through the point-of-view of its nameless protagonist, embedding you within the narrative just like a video game, Ralph never shows you doing anything like shooting anyone. Specifically, he makes a conscious choice never to show "your" hands grabbing or holding anything, even though "you" do exactly that many times. Those moments are elided, so the tell-tale FPS image of your hands holding a gun (or any other kind of weapon for that matter) pointed in the direction of something or someone you want to kill is nowhere to be found. It's first-person, but even when you do fire a gun, you never see yourself shoot.

It occurred to me as I read this collected, expanded edition of the comic (originally published in three installments by Bodega Books) and came to its grim, chilling new final page that Daybreak is better described as a first-person see-er. While your character occasionally takes action, intervening on behalf of the one-armed survivor who greets you with a friendly "Hello" in the first panel (and serves as your benefactor through most of the book), your main role is observer. This distinction has an effect on nearly every aspect of the comic at a fundamental level. Ralph's unwavering, densely packed six-panel grids relentlessly focus your attention on discrete sections of your environment; this enhances the sense that moment-to-moment survival is paramount, while the lack of peripheral vision makes you paranoid about danger lurking just outside your line of sight. Needless to say when we're talking about an alumnus of Fort Thunder, it's also an ideal way to showcase Ralph's often breathtaking drawings of the environment itself, a wasteland littered with crumbled buildings and mountains of detritus. It's so rubble-strewn -- it basically consists solely of rubble -- that it becomes hard to square with the contours of the zombie apocalypse as we know them, raising compelling and unanswered questions about just what the hell happened beyond our vision that made things get so bad.

The first-person seeing also has an effect on how you feel about the characters you encounter. The amount of time you spend with eyes locked on them as they look back at you, talk to you, help you, and seek your help in turn, naturally creates a sense of intimacy. In this kind of dangerous, kill-or-be-killed environment, that intimacy can feel good -- your friendships with the one-armed man and a very lucky dog, for example, exudes a warmth it might otherwise lack. But it can also leave you feeling exposed and vulnerable, as it does when you encounter a deranged and dangerous old man later in the narrative. The things Ralph forces you to look at during that passage have a blackly comic repulsiveness to them, an uncomfortable closeness to horror and madness reminiscent of the dinner scene in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which of course was itself shot in part from the first-person perspective of the cannibals' victim. As for the zombies themselves, perhaps the greatest indicator of their transformed, mindless status is that Ralph never lets us see them up close, never lets us look them in the eye. The eyes are the window to the soul, after all, and the undead don't have one.

Which makes that final page all the more upsetting. Ralph took what had been a happy ending -- a reunion with a beloved companion -- and added what amounts to a full chapter afterwards, leading to the book's single darkest moment. It consists simply of five panels of you staring at another...well, person's not the right word. The expression on his face shifts slightly and cryptically, his dark and hollow eyes stare back blankly. Your final act in the book is not just an act of seeing, it's an act of seeing someone who sees you in turn, with a gaze that carries in it all the weight of horror the book has brought to bear. It's a powerful, unshakeable image in an immensely thoughtful, carefully constructed, and ultimately troubling comic.