Why is a comic a comic and not some other thing? This question tends to get brandished most frequently in the direction of high-concept genre comics that one suspects were created because access to the big-budget filmmaking industry eluded their authors. But it's worth asking about most any comic, no matter the form of artistic expression that comes to mind when contemplating the alternatives. Is it a series of astutely composed images separated from illustration only by a sketched-in narrative skeleton? Is it an essay in comics drag, the art that should carry it serving as little more than glorified gutters between panels of the text where the authors' attention truly lies? Does it describe a thought the intensity of which masks its banality -- the kind of thing better left a private journal entry than offered for consumption as a comic to the world?

In creating Danny Boy, a comics adaptation of the lilting Irish ballad -- its melody the traditional "Londonderry Air" from present-day Northern Ireland, its lyrics written by English barrister Frederick Edward Weatherly in the 1910s, its presence ubiquitous among communities of Irish ancestry throughout the English-speaking world -- cartoonist Kjersti Faret makes the implicit argument that the comic serves a purpose the song does not or cannot. That, of course, is a tough row to hoe.

A perennial high-ranking entry on lists of Saddest Songs Ever, "Danny Boy" derives much of its power from its melody (the only part of it that befits Faret's billing of the song as "an Irish tune"), which miraculously manages to both build and descend simultaneously and is devastating to lachrymose Irish Americans like the present author within seconds. The lyrics are shamelessly sentimental, and often ahistorically distorted by contemporary Dansplainers into faux-rebel-song glurge about young sons of Erin being called off to war. But at heart they address a dreadful universal trauma, a parent's fear of being separated from her child, from a unique and troubling angle: The singer imagines herself dead in the ground, yet still awake and aware enough to long for her child's return to her grave. A prayer is hoped for, but Heaven isn't -- the land, the changing seasons, and the love felt for a child are the only lasting things. Now that "Danny Boy" the song has become Danny Boy the comic, is the transformation retroactively justifiable? The answer is a qualified no.

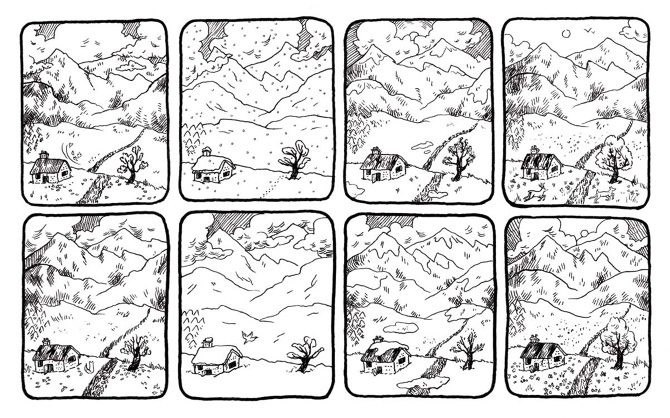

Judging from this and other work, Faret's interests in nature, myth/legend/folk tales, and their intersection is sincere and overriding, and that's one place Danny Boy works well. Its most solid sequences are the multiple stretches where the passing seasons that feature so prominently in the song are depicted in static landscape shots that repeat eight times per page. Snow falls and melts, plants blossom and wither, and the weight of years that will eventually bury the parent (here a father) in the child's absence is made visible. Though treating "Danny Boy" as an actual folk song is fallacious, it has become something close enough among the Irish diaspora, and in these sequences Faret captures a folk song's timeless communication of powerful themes.

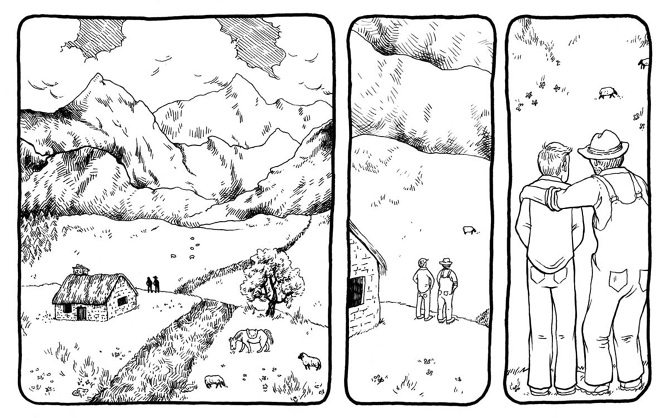

Would that she were as adept with the personal. Faret wisely drops the lyrics from the material entirely, dodging the dull "one snippet of poetry per page" trap into which countless would-be lyrical comics have fallen. But she doesn't replace it with dialogue of her own, in which the specific personalities and circumstances of this father, this son could be communicated. She misses a chance to compensate visually by obscuring the two men's faces throughout the comic, showing them from behind or from the mouth down but never allowing us to look into their eyes, see what they're seeing, feel what they're feeling. Human faces are a source of an unbroken emotional and intellectual broadcast, not just as generators of speech, but as the locus of facial expressions, laughter, tears, snarls, breath, a narrowing of the eyes, a widening of the pupils. Comics that drop the specificity that faces afford in favor of abstraction, simplification, or outright erasure had better offer a compelling reason to do so, an alternative that's just as communicative. Danny Boy doesn't.

The lack of a face to anchor our understanding of these characters draws attention to other problems with their presentation. Their proportions seem slightly off throughout, with the comic's vertical rectangular panels emphasizing their too-long torsos, weighing down their too-short legs. The panels can get cramped, too: In one sequence, the father appears forced to squeeze his arm against his body just to light his pipe. By the end of the comic, the landscapes that had been Faret's strength devolve considerably, with distant mountains becoming little more than the snowcapped triangles we all draw as children; the contrast with the crags of the opening panel is striking, though it indicates the problem perhaps lies in a dimunition of focus rather than a lack of skill.

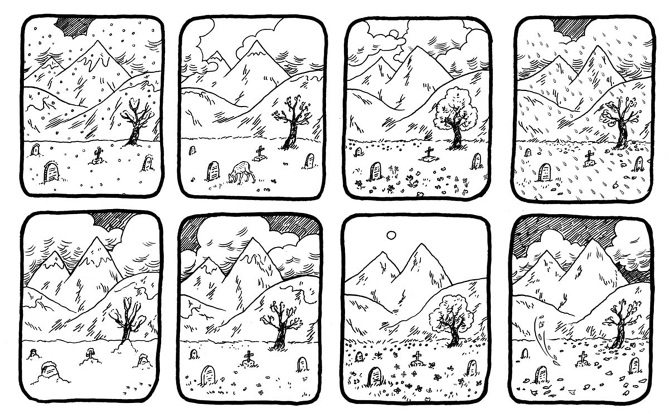

It's a shame in part because the ending is otherwise the strongest section of the comic, the one place where Danny Boy takes on a life of its own. It does so in death. In the end, father and son are buried side by side, first their bones and then even their coffins breaking down as the dark earth reclaims them. In the end, the totemistic pipe and locket that Faret had used as shorthand for each member of the pair are all that remain, and they too are disintegrated and consumed before the final black panel. A realist might question the staying power of a corncob pipe in a grave, while a reader partial to extremes might miss a full-fledged depiction of dead bodies rotting away into nothingness (admittedly this is where my sympathies lie), but both critiques are superfluous to the sequence's purpose, if not its power. In these final pages, Faret unearths an unspoken element of "Danny Boy" and puts it on display: The song's final line is "And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me," but of course at that point in the song the child has already returned, is in fact kneeling on the grave. It's death the parent is looking forward to sharing with his child, because only then will their reunion be complete. Faret shows what that would look like, taking the original and adding a stanza of her own.

Those final pages present a potentially rewarding path for Faret to follow as an interpreter of existing stories. It reflects the same sensibility on display in, say, her luminous, horror-tinged scratchboard illustrations for Arthur Miller's The Crucible. Though the whole point of Miller's witch-hunt parable is that the thing was bunkum, Faret casts her cast of goodwives in a seemingly supernatural light, suggesting that terrible forces and tremendous powers were in play here -- just not in the way the persecutors believed. Neither here nor in the end of Danny Boy is Faret indulging in the aforementioned glurge, lacing contemporary mores into past events in order to make readers feel good about their unearned ethical superiority (though she's not entirely immune to this temptation); rather, she's tapping into ideas and sentiments present in the characters and giving them freedom to manifest themselves in ways the characters could never do. Danny Boy may be a failed experiment, but in conducting it Faret has collected data that could well yield happier results a season or two down the line.