For some reason Spain Rodriguez – popularly known just as Spain -- is rarely described as one of the great autobiographical cartoonists, yet his stories about his teenage days and young manhood in Buffalo are prime examples of the power of comics to vividly revivify lost moments of personal experience. If there is an autobio pantheon that runs from Justin Green to Harvey Pekar to Art Spiegelman to Lynda Barry to Chester Brown to Alison Bechdel, then Spain deserves recognition as an outstanding member of this tradition.

Autobiographical cartoonists are often accused of being naval-gazing sad-sacks who regale luckless readers with trivial incidences from their eventless life. This stereotype hardly describes Spain, who at various points in his life could have been a minor character in Hunter Thompson’s Hell’s Angels or the inspiration for the Rolling Stones' “Street Fighting Man”. Spain has enjoyed an eventful, knockabout existence well worth reading about.

I’m particularly fond of the cycle of stories Spain has done for Blab magazine detailing the tail end of his teenage years and the onset of his adulthood, when he was apparently spending most of his free time with some buddies he calls “the North Fillmore intelligentsia” — a rather august name for a trio of guys held together by their love of EC comics and tendency to indulge in low level delinquent behavior.

The “North Fillmore Intelligentsia” (or NFI) stories are wry, affectionate, and even slightly regretful, thus very different in tone from Spain’s more famous autobiographical cycle, the vignettes from Zap Comix dealing with his years in the early 1960s with the Road Vulture Motorcycle Club (or RVMC). Violence-filled and snarly, the RVMC stories have an in-your-face orneriness that made for startling reading even when they appeared in a comic book next to the X-rated antics of Robert Crumb and S. Clay Wilson. One of the RVMC stories was titled “Hard Ass Friday Night”, a phrase which perfectly captures the attitude that permeates these tales. Aside from the NFI stories and the RVMC tales, Spain has also done a series of stand-alone autobiographical reflections on various aspects of his life (such as the impact of the cold war and his years as a blue collar worker).

Spain’s new book, Cruisin’ With the Hound: The Life and Times of Fred Toote', is a welcome gathering of his best autobiographical work from the last twenty-five years, although I have a few quibbles to pick with the way the book has been organized. The bulk of the book consists of the NFI stories, but there are also two RVMC tales and a sprinkling of stand-alone vignettes. Simply on the strength of the NFI stories, this is an essential volume since they give us a textured and convincing portrait of a working class industrial America that hardly ever gets represented in art or literature.

Perhaps the closest counterpart to Spain’s portrayal of blue-collar Buffalo is Harvey Pekar’s many stories of working-class Cleveland. Buffalo and Cleveland are both decaying Northeastern post-industrial cities that enjoyed their peak moments half a century ago, when the American economy still had room for people who made things with their hands. Despite their overlapping thematic concerns, Spain and Pekar took very different narrative tacks. Especially in his later work, Pekar tended to be introspectively ruminative and rarely trusted images to tell his stories (perhaps because he was only occasionally lucky enough to work with illustrators of the caliber of Crumb, Joe Sacco, and Joseph Remnant — as well as, on one occasion, Spain himself).

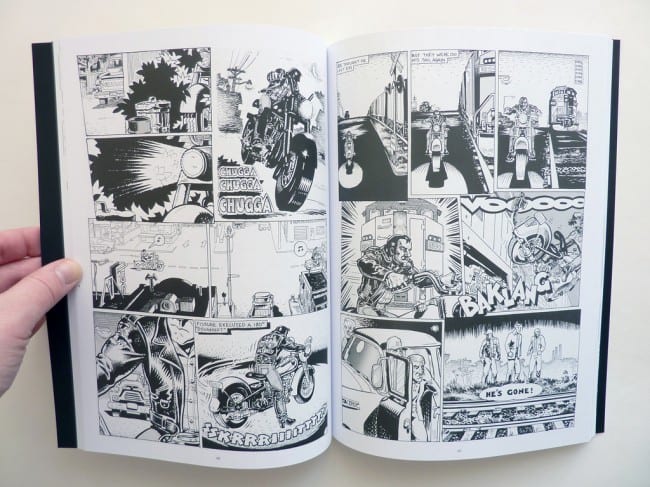

Spain draws his own stories, a simple enough fact which becomes central because of the strength of his drawings, striking images that look like they came from the hands of a more pugnacious and weather-beaten Wally Wood. Spain has a robust eidetic memory, so that the 1950s and 1960s Buffalo in these stories isn’t just a backdrop but a character as fully realized as the people. Equally convincing are period details: the full-bellied chrome plated cars, the sheen on the motorcycles, the inky-dark leather jackets.

To borrow a phrase from Chris Ware, remembering is a form of thinking. But the process of dredging up the past isn’t an abstract mode of ratiocination like solving a math problem or filling out a cross-word puzzle. Rather, memory is sensual thinking, involving a return to things we’ve seen, felt, touched, or smelled. When an artist like Spain possesses an energetic visual memory, his or her autobiographical comic has a special edge of persuasiveness because the drawings give us a window into the very process whereby the mind recovers the past.

Several times in this book, Spain alludes to EC comics as the taproot inspiration for his comics. While Crumb internalized storytelling lessons from Carl Barks, John Stanley, and Harvey Kurtzman, all of whom were masters of integrating visuals and text for story that had a headlong rush, Spain was shaped by the clunky text-heavy mode found in EC horror and science fiction comics (what I like to call the "picto-fiction" tradition). The strength of these comics often came from the power of single images of violence and decay, and the stern morality of revenge found in the story (vengeance continues to be a Spain obsession with many of his characters curling their lips in anticipation of exacting retribution). The weakness of the picto-fiction tradition is that the images rarely flow easily from panel to panel as they did the works of Barks, Stanley, and Kurtzman.

Many of the traits of the picto-fiction mode show up in Spain, notably captions which fill-in readers on information missing from the pictures and relatively static images that require time to decipher. Still, because he controls both the writing and drawing, Spain manages to avoid the major pitfalls of picto-fiction, notably the heavy redundancy that the EC stories possessed with pictures simply repeating the information already provided by the captions.

At his strongest, Spain moves beyond picto-fiction by having the captions and pictures in sardonic tension, as in a scene describing the miserable domestic life of a local tough guy. Over two panels the captions read: “The home life of James and his brother, Skippy, was not a happy one. Their old man liked to hit the sauce and frequently came home stewed to the gills.” These are unvarnished words but they take on the character of understatement as we look at the accompanying panels which show the father of James and Skippy not just drunk but reduced by liquor to an almost lunatic state where he mistakes the cupboard space under the kitchen sink for a bathroom and writhes around in demented agony.

Spain’s art has an uncouth vigor, calling to mind not just the obsessive vitality of the young Wally Wood but also the impudent starkness of graffiti. While working as a janitor for the Tonawanda plant of Western Electric, Spain came to admire the pornographic drawings that one of his colleagues, Ron Radetsky, drew on the bathroom stalls. Spain refers to Radetsky as “the Michelangelo of the lavatory wall.” I’ve often thought that part of the genius of underground cartoonists like Spain and Wilson was that they brought to comics the pornographic life-force found not just in the old Tijuana Bibles but also in toilet room graffiti, so it was gratifying to get some vindication for my hunch.

Many years ago while debating with Harvey Pekar about the relative merits of various cartoonists, R. Fiore astutely observed that “one thing that makes [Spain] unusual (and valuable) among American artists of any kind is that he’s not an individualist. In much of his work, the characters are not so much individuals as representatives of their social class (a time honored and perfectly valid strategy in satirical and didactic fiction). Spain paints his most convincing portraits not of individuals but of groups. In his motorcycle club stories, for instance, you learn very little of the personalities of any individuals, but a great deal about how they function as a group.”

We can push Fiore’s keen insight a step further by noting that Spain has a life-long tropism towards groups. He’s happiest when he’s involved in some group enterprise or distinct social milieu, whether it’s the North Fillmore Intelligentsia, the Road Vultures, or the Zap collective. He even had a brief childhood flirtation with Catholicism, an organization famous for its ability to foster group solidarity.

The NFI stories have the tentativeness of late adolescence, the chrysalis period when we’re unsure of what sort of adults we will be. The North Fillmore Intelligentsia consists of three guys: Spain, an eccentric named Fred Toote', and a hunchbacked body-builder called Tex. Sharing a love of EC comics, the trio are tugged in different directions by the competing claims of sex, art, and criminality. They admire local bad boys like James, who is in and out of prison for antics like beating up a cop, and the gangster duo of Wilcoxson and Nussbaum, who used a bazooka to rob a bank. “They were just businessmen conducting business with other businesses,” argues the young Spain.

The slightly-addled but endearing Fred Toote' is very skillfully etched out, especially with his propensity for off-kilter ideas. “I’m certain that I could evolve to the point where my body would use everything I ate so efficiently that I would never have to shit again,” Toote' tells his buddies as they share a meal at a local dinner. Toote' also predicts that he will “die a horrible death,” a dire prophecy that Spain tells us was fulfilled, although no details are provided in Crusin’ With the Hound. In an interview with Patrick Rosenkranz, Spain explained that Toote' “fell asleep with a lit cigarette in a drunken state and burned himself up.” The desire to memorialize Toote', to give some lasting account of what made him so central a figure in Spain’s youth, provides the wistful emotional core of the NFI stories and make them unexpectedly touching.

The Road Vulture stories, by contrast, are much more abrasive and antagonistic, celebrating a kind of outlaw masculinity built on reckless belligerence and a willingness to separate the world into sharp “us” and “them” camps. In the story “Mickey’s Meat Wagon”, members of the Road Vultures are driving back to Buffalo from Canada in a refurbished hearse with a guy named Mickey at the wheels. One caption reads: “On the way back we ran into a flock of seagulls. Mickey swerved into the middle of them just for savage amusement.” The next panel shows the hearse pulling into U.S. customs, its hood covered in dead seagulls. “Savage amusement” nicely encapsulates a key part of the Road Vulture mindset, although they also possess a roughneck gallantry that leads them to fight on each other’s behalf even in situations where the odds are long.

Cruisin’ With the Hound is a splendid book, a startling view of a plebeian world that tends to be submerged by the North American tendency to pretend that class doesn’t exist. The book is also evidence of the strength of the autobiographical comics tradition, which has room not just for minute introspection but also for stories of lively brutality. My only objections to the book are rooted in some of the editorial choices. Since I see the NFI stories and the RVMC vignettes as distinct both in mood and time period, I wish they had been separated out. As it stands, we have two RVMC episodes that interrupt the flow of the NFI tales. It would have also been good to have all the RVMC stories in one place. Right now, if you want to read all of Spain’s motorcycle club adventures Cruisin’ With the Hound has to be supplement with an earlier volume My True Story (which is regrettably out of print and apparently very expensive in the used book market). The RVMC stories will also be available in the forthcoming, very welcome Fantagraphics project reprinting Zap Comics in book form, but the material would still have greater force if concentrated in one place. Ideally, the best autobiographical bits from My True Story would have been gathered into Cruisin’ With the Hound. Still, these editorial quibbles are minor and shouldn’t prevent anyone from acquiring this necessary book.