There has always been something subterranean about Jesse Reklaw’s comics, and in Couch Tag, his first proper graphic novel and the story of his childhood told in five different ways, the fitful-sleep feeling of his work has found its perfect medium.

For his long-running strip Slow Wave, Reklaw illustrated people’s dreams that they submitted to him by mail. The eerie comics had a way of haunting your thoughts, just like your own dreams do some mornings. In 2010 he put out Ten Thousand Things To Do, a hefty little self-published chunk of a book that collects a year of diary comics. In that book, the disorganized daily life of a chronic insomniac is revealed, and we’re left with the image of a clever, unhappy eccentric who spends a lot of time with his cats. Combined with what we know of Reklaw as a former student of artificial intelligence and computer science (at Yale, no less), these interests and tendencies have always made him seem—to me, anyway—like an unusually intriguing figure. So it was with voyeuristic anticipation that I dug into his first memoir, Couch Tag, which has a beautiful and scary-looking painting on its cover.

And it got weird so fast!

The first part—the book’s five sections are described by Reklaw as novellas—is told as a series of stories about each of the pet cats his family had throughout his childhood. There were thirteen of them, and they all met a bad end—by dying of distemper, having too many litters, getting run over, or just running away. They were given names like Paranoid and Dead Duck by Jesse’s dad, and tripped with fishing line by Jesse himself on a day when he was feeling mean. Reklaw’s drawing style has a rounded softness to it, and the cutesy lettering of the chapter titles belies a nastiness underneath these stories. In this clever way, Reklaw manages to impart a queasy but subtle sense of unease and instability. If this is what became of the cats, what was life like for the kids?

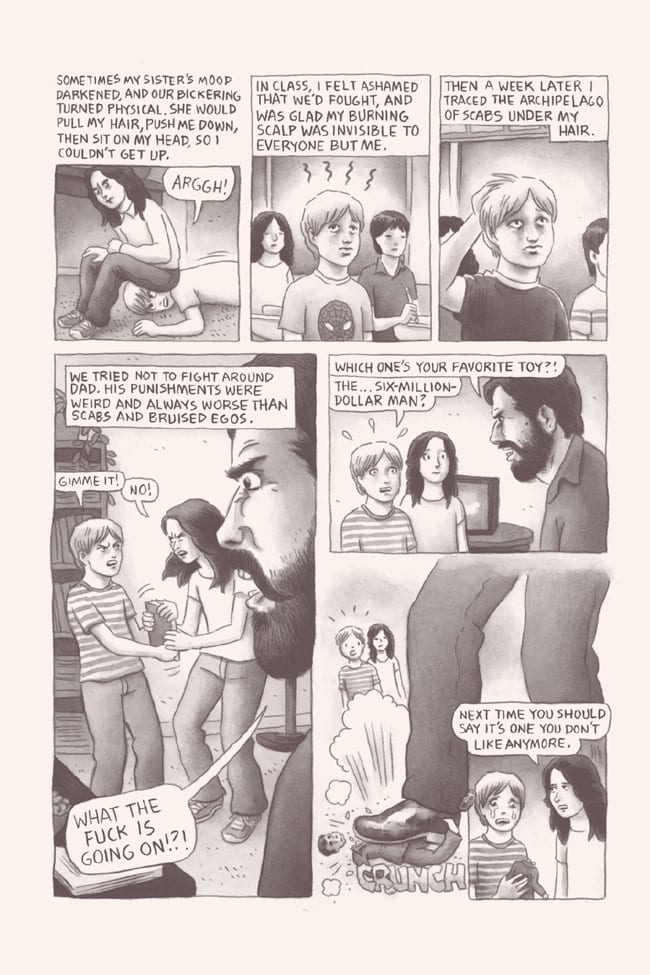

Jesse and his sister Sybil were raised in the seventies by rock-loving post-hippies who got married young and straddled the divide between sincere anti-establishment types who wanted their kids to grow up with a minimum of “hang-ups,” and irresponsible, angry potheads with shady friends. The family moved frequently, in search of better jobs, more affordable neighborhoods, or more “decent” people for the kids to spend time with.

The home lives of Jesse’s friends weren’t all that stellar either. He liked to hang out at his friend Noah’s house, he tells us, because the beaded curtains, pot smoke, and psychedelic rock reminded him of home. But in the next panel we’re presented with a close-up of Noah’s mom’s boyfriend, and the dude’s frowning face is interchangeable with all the other angry young dads’ that appear in the book, as if they’re all just one big long-haired hoard.

The home lives of Jesse’s friends weren’t all that stellar either. He liked to hang out at his friend Noah’s house, he tells us, because the beaded curtains, pot smoke, and psychedelic rock reminded him of home. But in the next panel we’re presented with a close-up of Noah’s mom’s boyfriend, and the dude’s frowning face is interchangeable with all the other angry young dads’ that appear in the book, as if they’re all just one big long-haired hoard.

“Often Noah’s mom wasn’t home,” Reklaw tells us in his deadpan way. "Her boyfriend sat on the couch, drinking beer and carving nude ladies out of soapstone.”

The word yikes comes to mind. But Reklaw rounds out the almost-story by saying simply, “Usually we played at my house.”

These kinds of troubling moments—the ones that leave most details off the page—call to mind Lynda Barry’s wonderful recent books (One! Hundred! Demons!, What It Is, Picture This) that dreamily evoke her own rocky, red-hued childhood. But unlike those kinda-memoirs, which chronicle Barry’s coming-of-age as an artist, this one rarely looks at its author’s creative impulses. (It’s also not in color until the final section.)

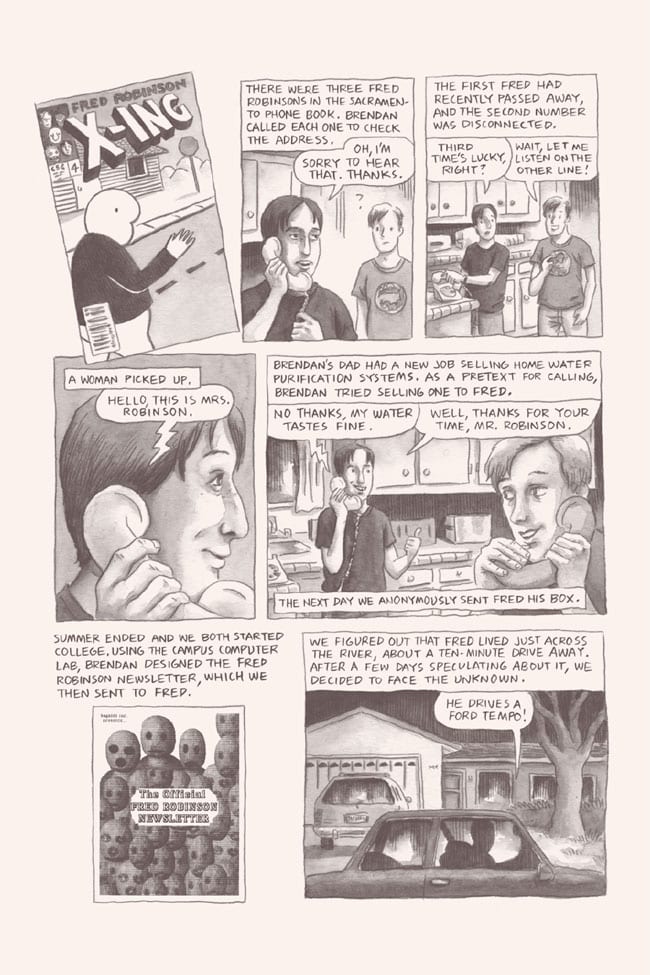

Eventually, though, a few personal details emerge that show us the preferences and habits of a budding artist. As a little kid Jesse collected interesting objects in his pockets, and he begged his mom for change so he could throw his findings down on the photocopier and “capture the day.” And by the time Jesse finishes high school he’s restlessly creative and certifiably weird, and is renting his mom’s house with his old friend Brendan. The person we first met as a formless, anonymous-looking kid is now an eccentric young adult with some delightfully oddball tendencies; even as he deals with tons of family nonsense and his own substance abuse, Reklaw is funny as hell. Equally uncomfortable with first names and stuffy titles, he calls all parents “mom and dad.” He and Brendan work on their loony music project and take breaks to sit outside and “critique the sunset.” (“Not bad. Could use a little more color.”) Somewhat more ominously, they stage an elaborate ongoing art project that involves tormenting some poor guy named Fred Robinson, whose name they chose at random from the phone book, by sending him scary music with his name incorporated into the lyrics.

To be sure, Reklaw’s imagination is wild, and he occasionally gives his family mythical status. There’s one story about a troubled uncle who lived in a trailer behind the family’s auto shop business, and as a kid Jesse thought it was like having Sasquatch living back there, an unpredictable hairy beast who was seen only when he emerged to use the bathroom or to get another beer. For the rest of the book, the man is always drawn as Big Foot.

But outside of these short jaunts into the realm of fantasy, the book is firmly rooted in the realistic. A little too firmly, sometimes, for my taste; with its many stories of family card games and “how I met your mother,” the book sometimes reads like a trip down memory lane. (And we all remember Tony Soprano’s irritable admonition about that, now don’t we? “‘Remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation.” Or, as Tori Amos has put it, “Just because it happened to you does not make it interesting.”

But the reason for Reklaw’s robotic storytelling style—well, that turns out to be quite a bit more interesting. Very occasionally throughout the first four novellas, he surprises us by admitting to a feeling that was, apparently, there all along. “We were always finding excuses to express our frustration and rage,” he tells us, just before teenage Brendan nails a kindergartner with a handball, and although we know that the kids have reason to feel angry and frustrated, Reklaw has given us no indication up until that point that those feelings were there.

It’s not until the final section that all is revealed. Rendered in murky purples and lurid splashes of red and overlaid with faint, scratchy words—thoughts and snatches of dialogue that come out looking like graffiti on the walls of his family homes—“Lessoned” is the story of Reklaw’s childhood with all of the emotions showing. Fear gives way to anger and despair, and no feeling is left unexplored. Reklaw’s story finally comes into full flower here, unencumbered for the first time by the weird stoicism that muffles the emotional life of the other stories like a heavy blanket.

Red lettering over orange backgrounds makes the words hard to read, and we have to strain to pull meaning out of the gloom. Soon, though, we understand that Reklaw is well aware of his emotional disconnect, and that in fact as a very young man he worried he had a split personality. Surprisingly, it’s not his tendency toward depression and apathy that he wanted to overcome but the sprightly intellect that leads him to moments of success, including attention from a Harvard recruiter and an interest in Nietzsche and Jung. This part of himself he calls the “ugly intellectual bully,” and he tries to smother it with drugs and drinking. Occasionally Jesse’s two personalities merge in beautiful moments of angry inspiration, as when he goes out at night on his own to steal a sign, just like he and Brendan used to do, and comes home with one that reads END CONSTRUCTION. The phrase has a double meaning for Jesse, who adopts it as his “readymade battle cry against society.”

I’ll look forward to the next full-length book from Reklaw, who has a truly special intellect and keen sense of humor. I’d love to see what would happen if he brought all aspects of his storytelling technique together at once.