“Everything I know, I learned from comics.” – Art Spiegelman

When you take the attractive, efficiently crammed trunk that is Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps by Art Spiegelman and unpack it using your careful attention, cultural knowledge, and your own unique experience of the world’s horrors, absurdities, and dubious pleasures – you might prepare to become an accidental magician, pulling from the trunk’s shadowy recesses a seemingly endless pile of colored pages, prints, sketches, book art, comics, trading cards, magazine covers and spreads, essays and information, posters, an entire comic book, and for the finale: a stained glass window.

When you take the attractive, efficiently crammed trunk that is Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps by Art Spiegelman and unpack it using your careful attention, cultural knowledge, and your own unique experience of the world’s horrors, absurdities, and dubious pleasures – you might prepare to become an accidental magician, pulling from the trunk’s shadowy recesses a seemingly endless pile of colored pages, prints, sketches, book art, comics, trading cards, magazine covers and spreads, essays and information, posters, an entire comic book, and for the finale: a stained glass window.

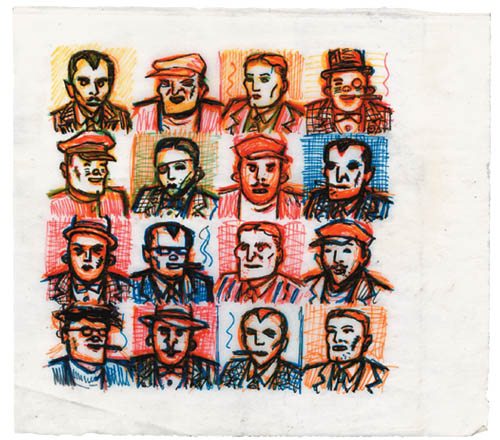

Act two: take any page from the impossible pile Co-Mix produces and unpack that. You will manifest a stack of interesting ideas, graphic innovations, formal experiments, insights, puns, self-psychoanalysis, dark satire, moral outrage, history lessons, humane and tender observations, surreal imagery, subversion, dirty pictures, and screwball gags.

Co-Mix is the most comprehensive survey of the art of Art to emerge so far, a dense, vibrating crosshatching of passionate comics-making and calibrated risk-taking. Recent Spiegel-books like Breakdowns (2008) and MetaMaus (2011) are deep-dish revisits of particular past works. Co-Mix also visits the past, but with a look at the entire arc of Spiegelman's journey as an artist.

This daunting, inspiring bouillon cube – selections from and about fifty years of intense, seemingly non-stop work by a passionate perfectionist -- may actually be too much for the casual reader. There's a lot of unpacking to do. In the 2008 reissue of Breakdowns, Spiegelman created a new introduction that has a higher page count than the original book, in effect unpacking some of the material for the reader. For the serious reader, anything more than a quick flip-through of Co-Mix, which is not concerned with interpretation or context, requires that you meet Spiegelman halfway. But when you do, his co-mixed comix become deeper and more meaningful. If you are interested in comics that offer something substantial, this is the stuff.

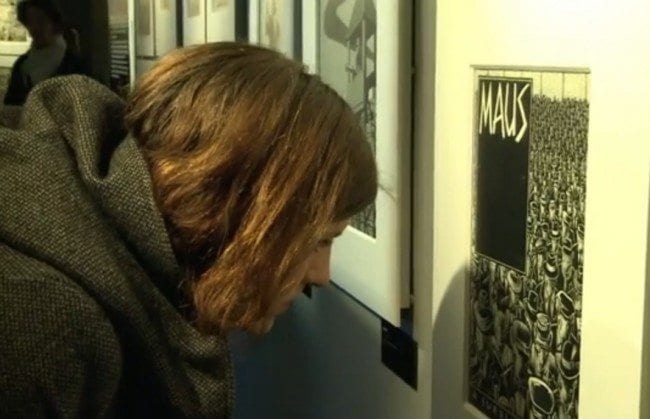

Co-Mix is not light reading, although it contains a great deal of humor. These are comics that use -- among other things -- sex, drugs, funny talking animals, and well-crafted comics to encourage one to think harder. A joke in a Spiegelman comic is rarely just that, being more often an inquiry: why is this funny? About ten years into his career, Spiegelman began to figure out ways to cram more and more information into his verbal-visual matrices, so that a medium supposedly for beginning and semi-literate readers actually tasks -- and rewards -- as much as art and literature. In addition to the mastery of information displayed in Spiegelman's comics, there is also a solidly grounded moral stance, fiercely taken, that challenges us to go beyond the escapist qualities of comics as entertainment. In Maus, the most obvious example, we can only fully grasp the story when we work to see past the animal forms of the characters, and refuse to de-humanize them -- a profound message that is essential to understanding both the historical reality of the story and the broad appeal of Spiegelman's work to so many people, including those who don't normally read or even "get" comics.

Spiegelman's work, seen through the wide-angle lens of Co-Mix is a quest to question everything in his life: childhood, culture, art (including comics), sex, drugs, politics, relationships, time, fatherhood, suffering, and history. If Rube Goldberg is what you get when you turn a person with an engineer's mind into a cartoonist, then Art Spiegelman is what you get when you turn a philosopher into a comics artist. Often, his work co-mixes what we might consider extreme opposites -- comics and genocide (in the 1970s, this was a radical idea for mainstream America), jazz and politics, the Crucifixion and taxes, hard-boiled detective fiction and Cubist art, to name just a few of the heady concoctions. The results both reveal new meanings and pose new questions. The work feels fresh and relevant, however, not because of Spiegelman's relentless formal experiments, but because of the tremendous personal investment put into every work. There is a humanity behind the intellect that makes the work resonate in both the mind and the heart. Spiegelman's comics may not be light reading, but they are enlightening.

In some recently published comments ("Artists on Artists: Art Spiegelman on the Varied Craft of Ad Reinhardt" by Carol Kino, New York Times, December 10 2013) for a showing of collage art comics from the mid-1940s by the famous "black-on-black" abstract painter Ad Reinhardt, Spiegelman notes:

"He used the Surrealism that he mocked in his text to invent a new form of comics as essays. When I walked into the gallery I realized how constructed these works are, how much attention it took to make them. This was a fully realized enterprise by somebody who really knew his business."

Spiegelman's own comics work in this way, as well.

There's a photogaph of Spiegelman at his art table in 1983, when he was subsumed into the work on Maus (an 11-year project). His eyes are shadowed, mouth grimly set, and there is a darkness to the air surrounding him. It's as if Spiegelman is not actually in New York 1983, but in Auschwitz 1944 - a place he had to go, in order to create Maus. While not every project of his has required such an intense journey to the heart of darkness, the sense of of high stakes permeates the work in Co-Mix. Spiegelman's pen strokes, his concepts, his writing, his images, even (or especially) the silly ones are all made as though his soul depended on it being done right.

And-- just a word here about Spiegelman's subjects. Among many other things, he's tackled truth in advertising (working from within), art history, the magical mechanics of sequential narrative, his mother's suicide, the experiences of a Jew in Hitler's Europe, literacy, and the terrorist attacks in America on September 11, 2001 (9/11). What emerges from Co-Mix, which covers Spiegelman's entire career to date in 138 pages, is the understanding that Spiegelman has been unafraid to tackle big, important subjects in his work. In order for comics in America to evolve and continue to gain respect and relevance, artists might do well to follow Spiegelman's trailblazing example: face the hard stuff.

An Un-Wacky Package: The Art of Presenting art

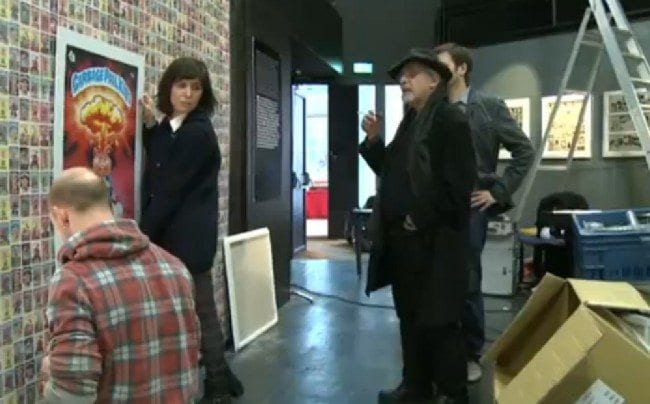

Co-Mix serves as a catalog for the exhibition of the same name that started in France at the 2011 Angoulême International Comics Festival traveled to Vancouver, B.C., and is now currently at The Jewish Museum in New York. The exhibit is a retrospective of Spiegelman’s work to date, masterfully curated by Rina Zavagli-Mattotti (and reviewed by Dan Nadel for The Comics Journal here). As with just about any project that is connected to Spiegelman, the book-catalog is impeccable in its execution and a good value, offering more comics, more art, and more ideas per pica than many similar publications. As such, it stands well on its own, separate from the actual exhibit.

Co-Mix serves as a catalog for the exhibition of the same name that started in France at the 2011 Angoulême International Comics Festival traveled to Vancouver, B.C., and is now currently at The Jewish Museum in New York. The exhibit is a retrospective of Spiegelman’s work to date, masterfully curated by Rina Zavagli-Mattotti (and reviewed by Dan Nadel for The Comics Journal here). As with just about any project that is connected to Spiegelman, the book-catalog is impeccable in its execution and a good value, offering more comics, more art, and more ideas per pica than many similar publications. As such, it stands well on its own, separate from the actual exhibit.

Presenting Spiegelman's ouevre in a more or less chronological framework, Co-mix begins with early zines and comics, progresses through Underground comix, trading cards, formal experiments , the 13-year creation of the graphic novel that changed the game, more books and magazine work, commercial art projects, a musical comics history play, a modern dance version of comics, and finally It Was Today, Only Yesterday– his giant eight by fifty foot stained glass comic strip permanently installed in 2012 at his alma mater, the High School of Art and Design. A section on lithographs closes the art section of the book, acting as a coda to the book, with material spanning the last 23 years. There are few mature modern artists who can deliver a catalog this fun and varied.

Drawn and Quarterly's classy package includes a front-loaded essay by author, film critic, and longtime Spiegelman friend, J. Hoberman (who also wrote the introductory essay to an earlier Spiegelman catalog in 1998). Hoberman’s essay is exquisitely written, and provides everything you’d want from a summing up created for a retrospective catalog. On the other end of Co-Mix’s arc is “Making Maus,” a 1991 essay by artist, critic, and curator Robert Storr (with a 2012 postscript in tiny print), a detailed, compressed work that peels back layers of meaning in Maus and suggests a model for how to consider the rest of Spiegelman's work.

The book includes at the back an extremely well done four-page chronology of Spiegelman’s life and work to date. The Chronology is stuffed with about 40 additional pieces of art, including a mini-cyclorama “endless” gag strip that runs across the bottom of the pages, art for a little-known Topps’ bubble gum product. Finally, the book concludes with a page of bibliographic citations that will prove useful to future Spiegel-scholars (and there's some lovely pix of Art and Françoise, too).

The beauty of Co-Mix is that, despite the creative maelstrom it barely contains, the richness and intelligence to be found on every one of its 138 pages mirrors the art it presents. We can even see in the book's binding a reflection of the Siamese twin wrestling match between high and low art, one of of the core themes of Spiegelman's work. The cover, two wrapped stiff cardboard slabs that hug and buttress a 9.5 x 13.25 trade paper book printed on creamy mid-weight stock – is a smart way to make a paperback work as a hardcover. It is perhaps too classy and understated to compete very successfully in a 2013 bookstore’s overstuffed “Graphic Novels” section (although it probably works well in a museum gift shop), but it struck me as a fitting package of Art Spiegelman’s art – making something elegant and new from mass produced, common materials.

In addition to the artful binding, the book includes two large fold-out pages, and a small color comic inserted into the book. It’s almost like a giant, deluxe issue of Spiegelman and Mouly’s 1980s RAW magazine – only this issue is all Art Spiegelman.

The book is an expanded version of a 102-page bi-lingual French-English catalog that was quickly pulled together for the exhibit and published in 2012 by Editions Flammarion. The look-and-feel of both volumes is very similar. Both editions were designed by the brilliant and gifted Philippe Ghielmetti (chosen by Spiegelman himself for the book), who also designed the big, beautiful Sunday Press books, including the recent stunning volume; Society Is Nix (see my review here). The Drawn and Quarterly, English-only version contains, Spiegelman estimates, “about 35 to 45 percent more.” The content has been reworked, removing the French part of the text, folding in rare art and new sections, and adding some extremely informative and well-crafted captions. “The new edition was coaxed inch-by-inch into becoming a much better book,” Spiegelman reflected.

Editors Tom Devlin, Jeet Heer, and Chris Oliveros clearly have a well-developed understanding and appreciation of Art Spiegelman’s work. Oliveros himself spent days with Spiegelman in his New York City studio, excavating layers of comics, graphics, and scraps but allowing the project to remain properly centered on the subject. “I’ve never been edited as gently as with Chris Oliveros,” Spiegelman stated. Every piece selected for this expanded version enriches our own understanding of this vital artist’s journey.

Retrospective Two Point O

Co-Mix the travelling exhibit is the second major retrospective in Art Spiegelman’s career, and Co-Mix the book is the second catalog of his work. In 1998, Centrale dell’Arte put on the travelling exhibit “Comix, Drawings & Sketches (From Maus to Now to MAUS to Now),” curated by Natalia Indrimi (it is interesting to consider how much of Spiegelman’s work has been shaped by women collaborators, most notably his RAW co-creator and co-editor Françoise Mouly). Also in 1998, Raw Books and Graphics designed and published Comix, Essays, Graphics, and Scraps (From Maus to Now to MAUS to Now) the intense, compressed German and English catalog, designed by Spiegelman, that accompanied the exhibit.

The titles of the two catalogs are similar, with the 2013 version inserting a hyphen that speaks volumes in itself, and removing the “Essays” part. Indeed, one major difference between the two catalogs is that the earlier version presents a wealth of Spiegelman’s published writings about comics and art history, each one of which is every bit as dense, intense, and jam-packed with ideas as his comics. Co-Mix is entirely an appreciation of Spiegelman’s graphics – and perhaps there’s a signal here that, in the last 15 years, this famously self-depreciating artist has come to uneasy terms with his stature as an artist.

Co-Mix also supplies the “first chapter” of Spiegelman’s first and early graphic work that is missing from the 1998 catalog (which begins with materials from 1977’s Breakdowns collection). There’s some endearing early scraps from Spiegelman’s first awkward newspaper comics and self-published zines. We also get a small sampling of art from Spiegelman’s early Underground comix stories, along with some never-before-published sketches. Best of all are the pages devoted to Spiegelman’s work for Topps – subversive commercial art at its finest (and it came with gum).

The other major difference between the two catalogs is, of course, the body of work created since 1998 (the endpoint of the first retrospective). Here is where we can discern a second meaning to the hyphen between “Co” and “Mix” (the first meaning is given to us on page 7: “To mix together. As in words and pictures.”) From page 77 on, Co-Mix covers new territory, presenting art and unpublished material from Spiegelman’s book projects (including In The Shadow of No Towers [2004], Open Me, I’m A Dog! [1997], and the Little Lit anthologies [2000-03]), his dense comic essays for The New Yorker and other magazines, poster art, commercial art projects including a Spike Jones CD cover, and a generous selection of previously unpublished, raw sketchbook drawings (including some grimly funny Death drawings from a time in 2012 when he was facing a serious operation -- in these images, which deserve a release of their own, a figure plays not Seventh Seal chess, but tic-tac-toe with Death ).

We also learn about “Drawn to Death,” an unproduced late 1990s music-theater collaboration with jazz musician Phillip Johnston – a play that explores in part 1940s Golden Age comic book artist Bob Wood’s beating to death of a woman friend with an iron, and Jack Cole’s suicide (in 2001 Spiegelman authored with Chip Kidd Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limits). Another “Co”- laboration is presented with some images from his commissioned dance performance piece with the troupe Pilobolus, Hapless Hooligan in “Still Moving.” Lastly, there’s an eight-page section on It Was Today, Only Yesterday, the colored window installation Spiegelman designed for New York’s High School of Art and Design.

When you look at where Spiegelman has been going artistically in the last decade or so, we can discern a strand of DNA coded to inevitably expand the form of comics beyond ink on paper. A connecting thread in Spiegelman's work appears to be a drive to realize, as best he can, the full potential of the art form we awkwardly have labeled "comics." Absent from the book – but included in the current incarnation of the exhibit in Brooklyn, New York is Spiegelman’s latest work from the last months of 2013, “Wordless,” a musical multimedia lecture created in collaboration with musician Phillip Johnston. What was supposed to be standard preparation for another in a series of Spiegelman’s popular public lectures evolved into an 8-month long project pioneering new ways to show comics on a screen and turn collective movie-watching into collective comics-reading.

Due to his success and the considerable mad props bestowed upon him by the fine arts world, Spiegelman has had unprecedented opportunities for an American cartoonist/comics-artist to play in a bigger sandbox. He’s MIXing it up, sometimes with some gifted COllaborators.

In the Shadow of Maus

The biggest challenge in absorbing Co-Mix, aside from the sheer amount of energy required to unpack the compressed works it contains, is the effort required to forget, for a time, Maus. Tellingly, Co-Mix offers up only 8 pages on Spiegelman's primary aesthetic endeavor from 1978 to 1991.

Since the 1986 publication of his book, Maus I: My Father Bleeds History, one might say that Spiegelman has had his coat-tails caught in the spring-loaded trap of fame, creating the problematic situation where the artist of today must compete with the artist of the past. As Spiegelman himself said in an interview conducted at the first incarnation of the Co-Mix retrospective in Angoulême in 2011, “Well, I was through with Maus many years ago, but it didn’t let me escape. I always had a five-hundred pound mouse chasing me.” Spiegelman, who was mobbed by reporters and fans in Angoulême, said this when his back was literally against the wall (which displayed Maus artwork), “I’d be glad to feel free to go,” he said with a mix of astonishment and panic, “but if you look around, I can’t even walk five steps. I’m planning an escape.”

From about twenty-five years ago to now, there has been a massive allocation of attention to Spiegelman’s Maus (the first part of which was published in 1986), while the rest of his work (and there’s a LOT of it!) remains un-integrated into any sort of larger context. The 1500-panel interlocking saga that stands today as Spiegelman’s Mausterpiece is a blindingly bright Cultural Phenomenon. Co-Mix may be a revelation for those that desire to squint past the brilliance of Maus, because it finally takes a meaningful step towards creating a context for the whole Spiegelman catalog (to date).

Some of the Things I Like in Co-Mix

A three-page comic on Charles Schulz and Peanuts3 that has more insight about comics than most books I’ve read (and is more entertaining, too).

A page showing 20 successive development drafts of a 1994 New Yorker cover4 -- the hatched flickers of Spiegelman’s artistic process makes the creation of art as magical and secretly painful as a ballerina’s pirouette.

The original art of 1972’s “Pluto’s Retreat,” the Kurtzman-Elder style panoramic splash page to Bizarre Sex #8 (printed just a little too small in Co-Mix to fully appreciate) in which classic comic strip characters screw each other’s brains out.5 (for example, Wonder Woman says, gazing at Li'l Abner's crotch which is obscured by the head of another character, "Gasp! NOW I know why they call you Li'l!") In this piece, you can see Spiegelman working towards the compressed density of Maus and later works with this piece.

“The St. Louis Refugee Ship Blues,” a hauntingly thoughtful and humane comics essay on political cartoons that is printed in color on the side of a large fold-out page.6

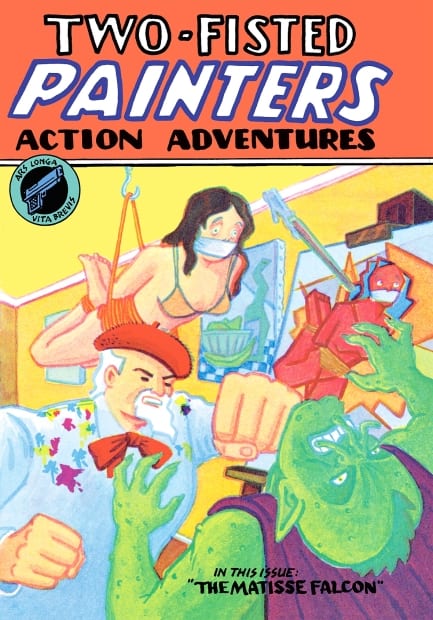

Two-Fisted Painters, a 12-page comic book insert, a facsimile of the comic-book-within-a-comic-book originally published in the first issue of RAW (1980). Spiegelman has said that the Co-Mix publication of his hard-boiled love poem to four-color process printing “is finally properly printed, with the correct coloring.”

“Spiegelman: The Early Years:" the transcribed text that is part of “It Was Today, Only Yesterday,” Spiegelman’s room-sized stained glass comic book page from 2012. Though it is a only fragment, this is the closest thing to a memoir chapter in short story from we have from this artist who is as adept with words as he is with pictures. I appreciate that the creators of Co-Mix took the trouble to transcribe and showcase the text, which would otherwise be inaccessible to anyone who cannot visit the actual stained glass installation at New York’s High School of Art and Design.7

Two pages of exceptional hallucinogenic book cover art made between 1978 and 1989 for German translations of the complete works of French author Boris Vian.8

The soulful, eerie Derby Dugan faux 1930s Sunday comics page, finally available to the masses in a larger size than originally printed.9

Artist Vs. Artisan

It is with the bringing together in Co-Mix representative samples of Spiegelman’s graphic work (most of which offer a book’s worth of ideas and entertainment value in themselves) that we finally can see that Spiegelman’s spinning energy has served as a sort of gyroscope for art in our time, valiantly forcing together for precious moments the repelling magnets of what we currently regard as high and low culture.

Co-Mix shows us that Spiegelman’s stubbornly and proudly sustained life as an artist, rather than as an artisan, has carried with it a certain energy that has pushed him out further and farther onto the scary, unfamiliar plain (where severe giant stone Happy Hooligan, Dick Tracy, and Popeye statues loom) than most others care to go.

What other college student in 1967 wrote for their art history class a publication-quality essay on something called “comics aesthetics”1? What other artist in the early 1970’s, inspired by the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward made a comic book story in scratch-board2. There were some pretty wild Underground comics artists, but only Spiegelman would, when tasked with coming up with a contribution to a comic book entitled Funny Animal Comics, deliver a dark, sad story about a WWII concentration camp with mice and cats as Jews and Nazis. No other popular artist has told the true story of a Jew in Hitler’s Europe in the form of a long comic book. There is no another artist who managed to put Jack Cole’s Plastic Man on the cover of The New Yorker. And, when 9/11 happened, it was with astonishing swiftness that Spiegelman created an iconic image that captured the broken heart of New York and America. Even in the post-Maus world in which there is a growing awareness of comics as an art form, can there be another well-known artist who has successfully turned comics into musical plays and stained glass windows? All of this – and more – is cataloged and revealed in the Co-Mix catalog.

The truth is that Spiegelman has been an invested, inspired, and courageous artist from 1963 to now, restlessly experimenting with mediums and concepts and creating a rich and diverse body of work over the last half-century that deserves to be seen outside of a certain large, mouse-eared shadow. For those willing to look, Co-Mix as both a travelling museum exhibit and a museum-in-book-form provides the means to study the work of Art Spiegelman the comics creator and artist in the context of something more than the creator of the Maus story.

As a 14-year old boy, Spiegelman visited his local public library, hauled a massive bound volume of newspapers from an earlier era down from the shelf and began his life-long study of comics history. It’s easier to see in the 1998 catalog stuffed with Speigelman’s essays on comics, but Spiegelman is as much a comics scholar as a practitioner. For decades, Spiegelman has sifted through what he calls “the slow burning forest fire that is newsprint” as well as numerous archives and collections stashed away in libraries and universities all over the world. He has not hesitated to seek out and connect with the actual artists and writers that interest him (he and Françoise Mouly once spent a week hanging out with science fiction writer Philip K. Dick at his California home).

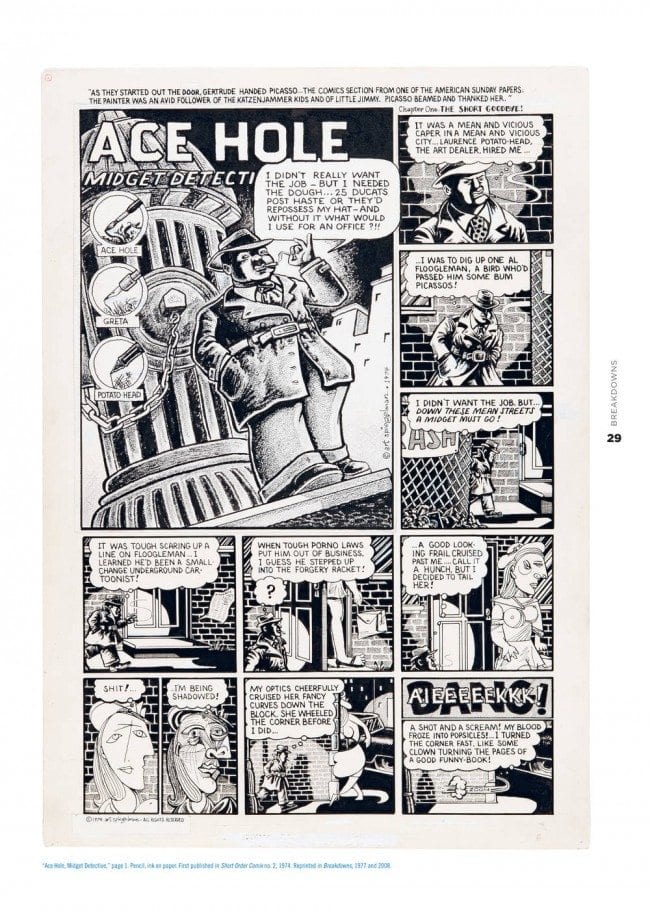

Spiegelman’s journey to know more and understand more about his chosen profession is a key to understanding his work. Many of the pages in Co-Mix are as much about the form of comics as they are about anything else. Spiegelman has made a consideration – and elevation – of the art form one of his primary concerns. Early comics like Ace Hole, Midget Detective and The Malpractice Suite (the original art of this 1976 two-pager) acquire from, manipulate, and comment on comics as an art form, as well as comics as cultural history.

By the time Spiegelman sat down to make Maus, as Co-Mix shows, he had already created a body of work that would have at the very least, made him a cult favorite. With Maus, his conversation about comix shifted to the background. In the multi-layered story, he portrays himself as the cartoonist he is, which is a way of working comics in -- but much of his fascination with the form is shown in his uncanny ability to fold comics into themselves, so that the very design of a page becomes artful when the content it presents is considered.

As the new retrospective and a few pages in the catalog show, Spiegelman drew and re-drew each of the 1500 panels in Maus, sometimes dozens of times. Drawing does not come easily to him, and his joy is not that of an ice skater gliding gracefully across the ice, but more that of a sculptor, determinedly chiseling pieces away with cut and bruised fingers to find his form.

Perhaps his deep connection with the artists of the past who created those magnificent “silent” woodcut novels is more than formal. Spiegelman viscerally identifies with the struggle and the mad integrity of the woodcut graphic novelists from earlier eras such as Franz Masereel and Lynd Ward, who sweated to carve and reshape blocks of wood to make their art. I once had the opportunity to study Art Spiegelman's hands as they made a quick cartoon drawing to accompany an inscription in a book. He used a fountain pen that he dug so hard into the drawing surface, I could hear it scraping into the paper. There's a need in Spiegelman's art to fight for its place -- in this, he seems a quintessential New York artist.

The copy on the back of Co-Mix culminates with a definition of Art Spiegelman as “an artist whose work has been genre-defining.” That is almost a fair statement to make about a comics master whose "comic that needs a bookmark" was instrumental in the rise of the modern graphic novel. However, “genre-destroying” seems much more right to me, when it comes to hanging a label on Art Spiegelman, who has resisted hewing to anything close to a generalization.

In my lifetime (I was born in 1962), I have seen the works represented in Co-Mix attack, weaken, and in some cases break through conceptual and commercial walls to allow comics more room to thrive. Could anyone in 1940, 1960, or even 1980 have imagined comics working as a wall-sized stained glass installation, itself a Krazy brick smashing through the glass windows of the definition of comics? Now that this has been done, and carried to artistic success – we are barely yet able to grasp where this leaves us in understanding what comics actually are.

Art is, in part, destruction. To make art, things have to be pulled apart and strewn all over the room before they can be re-fashioned into something new. And, they probably have to be laughed at, as well. Spiegelman’s work, while whole and complete in itself, is imbued with an energy that unleashes a healthy and needed de-constructive force to the world around it.

Ultimately, Co-Mix is dense, messy (despite it's beautiful design), unwieldy, demanding, and anything but a definition of its subject. This is good. Be suspicious of art (and Art) that is too easily packaged.

Notes:

- “Bernard Krigstein’s Master Race: The Graphic Story as an Art Form” (First published in The Harpur Review, 1968 and reprinted in the E.C. comics fanzine Squa Tront #6 (1975) and in the 1998 retrospective catalog, Comix, Essays, Graphics, and Scraps (1998, Raw Books). See also "Ballbuster: Bernard Krigstein's life between the panels," (The New Yorker, July 22, 2002), in which Spiegelman reviews B. Krigstein; Volume One (1919-2002) by Greg Sadowski (Fantagraphics Books, 2002).

- “Prisoner On The Hell Planet” (Short Order Comix #1, 1972) tells the story of the suicide of Spiegelman’s mother using scratchboard, a "page"of China clay coated in black India ink. Knives are used to "scratch" away parts of the ink to create stark, black and white images that emulate the woodcut look. Most of the six woodcut novels that Lynd Ward created between the years 1929 – 1937 were not reprinted in America until 2010, as a two-volume set in Penguin’s Library of America series. The books’ editor: Art Spiegelman, who also contributed the introductory essay. Will Eisner, the other American comics artist interested in the time in creating a long, literary comic book, cited Lynd Ward as an inspiration as well. Spiegelman has mentioned that several of the Underground Comix artist he knew in the early 1970s were hip to Ward and the other woodcut novelists.

- “Abstract Thought Is a Warm Puppy,” pages 77-79 in Co-Mix.

- Co-Mix, page 59.

- Co-Mix, page 23. Compare to the Goodman Beaver stories created by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder, especially the banned story, “Goodman Goes Playboy.” The orgy splash panel from this story, reprinted on page 10 of Goodman Beaver by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder (Kitchen Sink, 1984), is similar to Spiegelman’s cartoon character orgy.

- Co-Mix, page 90. Spiegelman has created several notable essays on comics using the form of comics themselves, most notably “High Art Lowdown,” which appears on Co-Mix, page 7.

- Co-Mix, page 112.

- Co-Mix, pages 32-33.

- Co-Mix, page 122. This lithograph was originally created for Tom DeHaven’s 1997 novel, Derby Dugan’s Depression Funnies, a story about American newspaper comic artists in the 1930s (the middle book of a trilogy about comics in America). Spiegelman also created the art for the book’s dust-jacket, which is reproduced in Co-Mix on page 95.