Citizen Jack, the new series by Sam Humphries and Tommy Patterson, tells the story of an unlikely presidential candidate—belligerent ex-small-town mayor Jack Northworthy—who gains ground in the race to the White House after making a deal with a demon. If demon brings to mind special-interest groups or career politicians, you’ve grasped the richness of the allegory. The comic aspires to capture the absurdity and deceit of contemporary US politics. But with its antihero lead, its telegraphed relevance, and supporting characters such as a battle-axe ex-wife and a no-nonsense campaign manager, Citizen Jack reads more like proof of concept for a second-tier cable drama than an effective political satire.

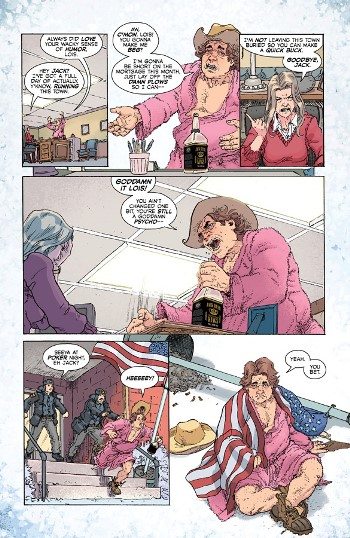

Issue one begins with lines of stock dialogue from Jack (“Every man makes his own damn decisions … I just made mine”) and follows them with lines of stock narration (“Ever since he was a kid, Jack Northworthy dreamed of being one thing … Things didn't quite work out that way”). To define their lead further, Humphries and Patterson rely on a kind of characterization by association. The comic takes for granted Jack’s place among more memorable rogues: he rides a snow plow through the main drag of his Minnesota town, wearing a bathrobe-and-cowboy-hat ensemble, drinking whiskey from the bottle, and evoking Tony Soprano, Jeff Lebowski, and Bluto Blutarsky. The likenesses don’t flatter this comic. (Sure enough, Jack has daddy issues, too; the sequence following his plow ride includes an armed standoff between father and son straight out of Justified.)

From these pages begins a satire that even the most obtuse reader will recognize. After being dressed down by his ex and then by his dad, Jack decides to run for high office. This announcement—to a crowd of four, atop a frozen lake—leads to the issue’s best page. Jack kicks off his campaign by removing his clothes and taking a dip in the lake’s frigid waters. We see him go under the surface and then through a demonic seascape, a visualization of his mystical benefactor’s reach. The image gives Patterson a chance to show Jack in motion and colorist Jon Alderink a spacious, textured canvas with which to work; their efforts lend the scene a sense of weirdness and possibility not found in surrounding pages.

From these pages begins a satire that even the most obtuse reader will recognize. After being dressed down by his ex and then by his dad, Jack decides to run for high office. This announcement—to a crowd of four, atop a frozen lake—leads to the issue’s best page. Jack kicks off his campaign by removing his clothes and taking a dip in the lake’s frigid waters. We see him go under the surface and then through a demonic seascape, a visualization of his mystical benefactor’s reach. The image gives Patterson a chance to show Jack in motion and colorist Jon Alderink a spacious, textured canvas with which to work; their efforts lend the scene a sense of weirdness and possibility not found in surrounding pages.

Here and at many other points in Citizen Jack’s first issue, Patterson’s cartooning resembles that of Chris Burnham, though with fewer post-Quitely flourishes and a less acute eye for the grotesque. In fact, Citizen Jack would benefit from a more obvious signaling of where its grotesqueries begin and end. Throughout Burnham’s issues of Batman Incorporated, that artist rendered characters from Bruce Wayne to Gotham City’s various creeps in a stylized manner but with a keen sense of scale. A reader understood, for instance, that even Burnham's waxen, bug-eyed Wayne was a handsome man in the context of this world and the comic’s monsters were not.

Patterson's figure drawing is easy enough to follow, but he lacks consistency and a sense of proportion on the level of a peer like Burnham. For instance: although we learn that Jack Northworthy has certain charms, the extent to which he owes these charms to his looks (or the extent to which his looks have held him back) isn’t certain. The depictions of his face vary often enough, if in subtle ways, to render this unclear. (And that’s excluding a scene in which Patterson draws Jack the way Jack wants to see himself.)

But these aspects of the comic, while not trivial, don’t contribute to Citizen Jack’s failure to tell a new, resonant, or amusing political story as much as Humphries’ script does. By the time Jack announces his nominal campaign, the comic has not shared any real indication of his politics. The closest it gets is Jack’s charge that, “Political elites are killing this country,” one of the few things members of both party bases might agree on. Armando Iannucci (Veep, The Thick of It) has included similar ambiguities in his work, and like the comic’s resemblances to some much-loved earlier antihero stories, this would put Humphries and Patterson in good company. Even so, throughout Citizen Jack, the choice plays not like a bucking of politics-as-usual but like an unwillingness to alienate any reader too soon.

Later, via a bland burlesque of cable news, the first issue introduces Jack’s competition, the presumptive nominees of … the Patriot Party and the Freedom Party. Humphries may well have an extensive rationale for this choice, but it reads like still more fence straddling—another feature of a story that services the impulse to say, “Boo! Politics” while seeking to challenge no one.

The same cable news sequence reveals that footage of Jack’s campaign-kickoff plunge has gone viral. Like most of the other story beats in Citizen Jack, this one’s aggressively familiar, and it leads to more of the same: a savvy campaign manager drops into Jack’s small town, because, “The great American political cycle needed fresh meat.” (Later, she says things like, “That’s how we play the game.”) This … it’s just the same junk a person would find in Head of State or Man of the Year or any other story in which a straight-shooting outsider finally shakes up the political establishment. Citizen Jack looks at a deeply dysfunctional system—with flaws that actually hurt real people—and doesn’t find more to say than, What a circus, huh? The first issue is only the earliest part of a longer story, but it’s a dire read that promises few improvements to come. Like so many lousy politicians, Citizen Jack falls short despite its endless calculations.