Children of Mu-Town comes alive at night. There’s something about Masumura Jūshichi’s artwork that seems a bit stiff in scenes set in brightly lit spaces, whether under the harsh light of day or the fluorescence of overhead lamps in cramped, bright rooms: their figures are a little static, a little blocky, backgrounds are left to the imagination whenever possible. But when nighttime fills the panels, the art becomes vivid - jet black spaces filled with flickering white-out smears of little city lights, movement rendered in full, thick brushstrokes. When travelling Mu-Town after dark or under the swollen oppressive hatching of clouds and fog, the apartment complexes loom above men like phantoms, like gods; towering shades and whispers.

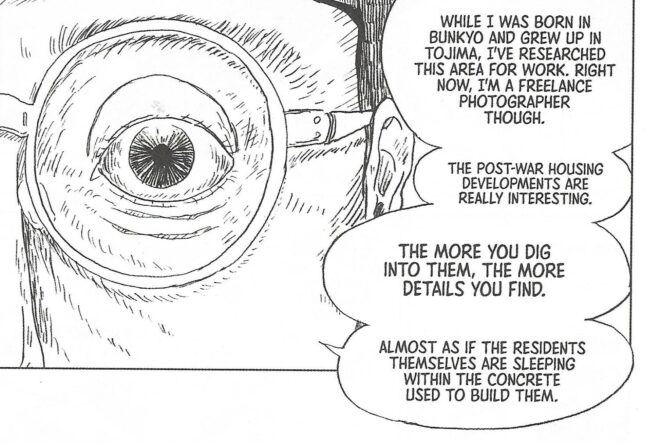

The titular Mu-Town is an aging housing project, Marigaoka Park Town - the former “Murray Town”, a product of postwar development. The development's Children are the 22,515 residents who occupy her old concrete walls. This is the home of immigrants, yakuza, elderly people, societal dropouts with nowhere else to turn, and their children - children who have become adults in this place. This gargantuan yet plainly brutalist unit once contained a dense overflow of population with inhumane regularity, harsh permanence. Housing developments are a sort of urban regulatory body, containing and stifling the impoverished to maintain a tight headcount. And yet, after 60-some years, this ever-present modernist structure has aged and declined, and perhaps grown warm. At half-capacity, the place is as teeming with absence and memory as it is with people. Communities, cultures, human ecosystems have formed around the heart of a bureaucratic beast. Such evolution could be cherished, but in the capitalist eyes of urban developers, this is like a dying dog to be put out of its misery, failing to serve its maximal potential in terms of the land’s worth.

Children of Mu-Town is about watching a home decide whether or not to leave itself. Each chapter observes a few daily activities in people’s lives -- games of cards, trips to the convenience store, drinking and smoking in groups, a professional woman working quietly at her desk -- as well as people’s departures: to nursing homes or job opportunities, little pushes out of this humble dwindling de-facto vertical village, embedded in the looser fabric of Tokyo’s urban sprawl. There are needs, there are dreams, there are reasons. Nonetheless, there is also loss; something passing that may never quite have ever been, almost unspeakable. The focus is not unlike the setting that Katsuhiro Ōtomo mined for action sci-fi in Domu: A Child’s Dream and his film World Apartment Horror; it feels strongly reminiscent of Taiyō Matsumoto’s observational works about schools and orphanages, like GoGo Monster, Blue Spring and Sunny, but the specific tension that drives Masumura’s work is the phenomenon of a small community losing its identity to the pull of a city that exists within the city itself - an accidental defiance of normative urbanity slowly pulled apart toward the magnetic center of postmodern metropolis.

As with the Matsumoto titles, Mu-Town is neither an ensemble piece nor centered around a traditional protagonist; rather, it follows a complex social bond between two men who, in some sense, exist adjacent to the place they notionally inhabit. Juichi wants to transform Marigaoka into a “model town” that can survive the rapid departure of residents and overcome the stifling presence of yakuza affiliations. Juichi is alienated from Marigaoka, and that alienation deepens as he takes on the role of arbitrator, petitioning his community for changes they don’t want or understand, and might not pan out as he hopes. And yet, his desire is for this declining edifice to persevere. He never left home and never wanted to, and he faces the difficult possibility that his home might leave him instead. Hajime, the second man, is disturbed - his face is always partly obscured by a domino mask, or perhaps face paint. He is in some sense a person of impulses: brawling, gambling and drinking, his massive body slouched in cramped rooms, blaring the Clash on his stereo. Like Juichi, Hajime is in some sense adrift and alien within Marigaoka, but he is also rooted in it, accepted by the community if not always understood. He thrives in this building; in his own little way, he needs this place in order to continue existing on his own terms. On an intuitive level, he knows this space sustains him.

Parallel to this orbit of difficult male friendship, two women are connected to Juichi and Hajime’s conflict, who each have a different relationship to Marigaoka. Minori, Hajime’s cousin, wants to leave Marigaoka, or at least find work outside the building’s shops and establishments - a rupture in the tight ecosystem Juichi strains to preserve. Minori wants to leave this place, but she understands that Marigaoka shelters a living community, and holds her roots - this sense of loss is what Juichi strains to ignore, in his endeavor to transform the town. Juichi’s methods are interrupted by the arrival of Karen Gordon, a popular American singer who lived in Marigaoka as a child with her Army dad. Now that her music career is in its twilight, Karen has found work as the figurehead for an NGO-led project euphemistically termed “community organizing”, a program of urban development explicitly compared to projects led by Barack Obama prior to his presidency. Karen is a mercurial presence in the book, harnessing the energy Juichi built in the hopes to barely sustain Marigaoka, and redirecting it toward a program for rapid urban development that destroys and displaces under the pretense of renewing.

On paper, Karen’s plan is a progressive project - a placement program to fill the barren apartments of Marigaoka with recent immigrants to create a “model town”. But with no other real infrastructure, what she is building is a locus for impoverishment where older residents -- themselves often from immigrant and minority families -- will be pushed out of residency and lose what few supports still sustain them, while new residents will be harassed, neglected and heavily policed. As Juichi coolly observes: “The unease people feel will lead towards anti-immigrant sentiment, which will lay the groundwork for the hawks in the government to gain power.” Karen's project is not a revitalization at all, but a destructive act: a restoration of post-war atomization that dissolves communities and stokes those resentments which advance fascism. Consumed by her political motivation, implementing this callous, coercive agenda might be the closest that Karen can bring herself, an American raised on the foundations of an outpost of occupation, to experiencing nostalgia for her childhood home.

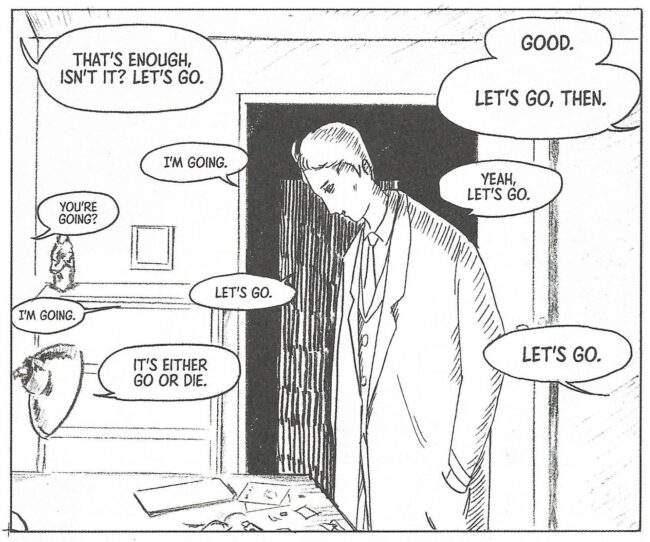

As we travel across the pages of this comic, its setting seems to fall away until every bit of our attention is drawn to these four people and the political conflict played out between them - centered around Marigaoka, but positioned outside that community sat within the development's concrete façade. Fittingly, the bulk of the story's closing chapter rockets the reader out of Mu-Town, as Juichi, Hajime and Minori speed off in a stolen luxury car, pursued by a masked gang of racists who have made Hajime their enemy. Driving into the night, into the depths of Tokyo, the gleaming frame of the vehicle reflects the electric lights of an urban place much larger, more crowded, emptier, more anonymous than the homely sights of Marigaoka and her stably defined walls; the characters have entered an atomic space that is everything else, as well as nothing. It’s some kind of promise to go somewhere, in the beautiful city - the idea of leaving home, and a homecoming, woven into one potential event. Yet as the three race further away from Mu-Town, the building’s shadow looms larger than ever, light streaming brilliantly from curtainless windows in a glorious splash page. They are traveling -- or wanting to travel -- to that place, the real home where they will always live, and to where they can never totally return.

There is an appropriate perfection to Masumura’s draftsmanship, one that becomes more evident the longer you dwell in these pages. and the more often you return to them. In every illustration, one thing will slowly reach your attention as impeccably rendered - each stiffly gestural mark comes alive with the variety of weights and textures applied. The craft on display here has the personality we want when we ask for “alternative” comics or “independent” comics: that beautiful feeling of reading a work of personal observation; lines that feel like a human voice of their own; a pen or brush on paper telling you in every way possible a story about the person whose hand guided such words and pictures into being. Like the tenement buildings I’d see out the window of a car or a bus when I was little, or I'd step inside shyly to visit a friend so much like me -- like the semi-fictional Mu-Town on the other side of the world, but not unlike those buildings I know -- what at first seems stiff, blunt, large, small, not-quite-there, first becomes elusive and mysterious, and then becomes human, warm, known, immediate, expressive, living, precious. The beauty so apparent in those night scenes and those gorgeous and haunting exteriors, the sights seen when outside a building - slowly, that beauty seeps into the interiors, casually present for the accustomed reader’s eye to find. Dwell in these pages for a while, and do not forget to return to them. Everything becomes a little more beautiful after the first time you leave.