Glenn Head’s Chicago, a coming-of-age memoir, is firmly rooted in the old-school, underground, rebel comix tradition. The cover illustration fairly announces this, with its detailed depiction of the protagonist panhandling on a squalid urban corner, featuring an actual word balloon, giving it the throwback feel of the post-underground comics of the '80s and '90s. This offers a challenge of sorts to the high-toned, New Yorker–reading crowd, who, in theory at least, lean toward graphic novels that don’t advertise so explicitly that they are, you know, mere comics. But Head has more up his sleeve than a simple UG autobio tale. Chicago is also an intricate, literary story, with a protagonist whose motivations are often opaque and with outcomes that are anything but expected.

As Phoebe Gloeckner points out in her eloquent introduction, the story begins and ends in a graveyard. The specter of death haunts the edges of this tale, unusual in a coming-of-age memoir. Throughout, Glenn Head’s protagonist “Glen” (one ‘n’ missing, likely allowing for some artistic license regarding “truth”), skirts the limits of mortality, stepping deliberately into dangerous situations for reasons that remain hazy, even to himself.

The book begins with a prologue in 1977 suburban New Jersey. Nineteen-year-old Glen, recently graduated from high school and set to begin art school in Cleveland, loafs about, immersing himself in underground comix and books by experimental writers. He exclaims over his copy of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch: “It’s like everything’s fractured, broken down, busted apart—no rules! His own universe…” He is fascinated by his friend Sarah, daughter of Holocaust survivors, who lives a much more volatile existence, and gets pregnant as a result. “She’s this beautiful wild girl,” he thinks, “just out there living, man—like whatever happens!! And I’m here in this nowhere scene…”

Glen is clearly waiting for his life to begin, a virgin in more ways than one. In the next chapter he goes off to art school in Cleveland, but he takes none of it seriously. He mouths off to his instructor, skips classes, begins having weird hallucinations, and largely secludes himself in his increasingly squalid dorm room. When he ventures into the ghetto just outside the comfortable confines of the school, he sees the bloody aftermath of a botched pawnshop robbery, with five people shot dead. “One day I’ll be dead,” he thinks to himself. Soon after, at a classmate’s random suggestion, he takes off for Chicago with just the clothes on his back and his portfolio—which he has vague plans to show to Playboy magazine.

The Chicago chapter is the obvious core of Head’s book. In it, we see his youthful bravado come face-to-face with the harsh realities of being homeless and penniless. Through the kindness of a stranger, an African-American man named Aaron, Glen is given shelter, although he still has to scrounge and panhandle for sustenance. He fights starvation and fends off street predators, quickly realizing that the coolness of “living on the edge” is a lot easier to read about in comix than it is to actually experience.

Some of his youthful boldness and aggression does pay off: he brazens out a meeting with Skip Williamson at Playboy and ultimately gets a small illustration gig. Through Williamson he also meets Robert Crumb himself, whose cynicism with regards to the underground comix scene surprises Glen (though certainly not readers familiar with present-day Crumb). In another brush with a living legend, Glen chances upon Muhammad Ali, who has drawn an admiring crowd outside a department store. For no good reason, Glen recklessly and obnoxiously antagonizes Ali. Eventually, after more scraping by, Glen returns home to his parent’s house in New Jersey, somewhat chastened, but still unable to reconcile his experiences on the streets with this cloistered upper middle-class suburban existence. In a bizarre sequence that closes out this section, he deliberately, though almost offhandedly, risks his life while goofing around with his father’s gun.

The final section of the book fast-forwards to 2010. Here we meet fifty-something Glen, leading a much more sedate existence in Brooklyn. He is divorced, with a strong-willed but seemingly emotionally healthy young daughter, Kay. Glen is now sober, and his one “dangerous” vice is visiting a so-called gentleman’s club, where he politely declines a lap dance. There’s a shaky sense of calm to him, a careful control. Then Sarah, the friend Glen hasn’t seen since 1977, suddenly makes contact: “She’s alive,” he tells himself repeatedly, knowing full well how easily the opposite might have been true. Sarah visits and together they take stock, looking back at how the years have gone for each of them, how they’ve changed, and how they’ve survived all that life has thrown at them. The book ends on an elliptical note, with Glen and daughter Kay idling away some time in a graveyard. There is the suggestion that Glen is quietly imparting the importance of the cycle of life to Kay, and that he has reconciled himself to it, no longer flirting with the abyss.

Glen is a difficult protagonist, unlikable in many ways. There’s no sense of anything being at stake in the risks he takes. They often seem like the foolhardy self-indulgences of a pampered rich kid, with “dangerous” artistic pretensions. But even in his run-in with Muhammad Ali, he seems to act not out of genuine malice but with a weird how-far-can-I-go rashness. In contrast with fellow comics autobiographer Joe Matt, who deliberately makes his comics persona as obnoxious as possible (to often hilarious or infuriating effect, depending on who you talk to), Glen is simply a really mixed-up, impressionable kid, with a host of mental health issues to boot (the narrative offers only clues as to what these might be, though at times he certainly appears dissociative, and quite possibly bipolar).

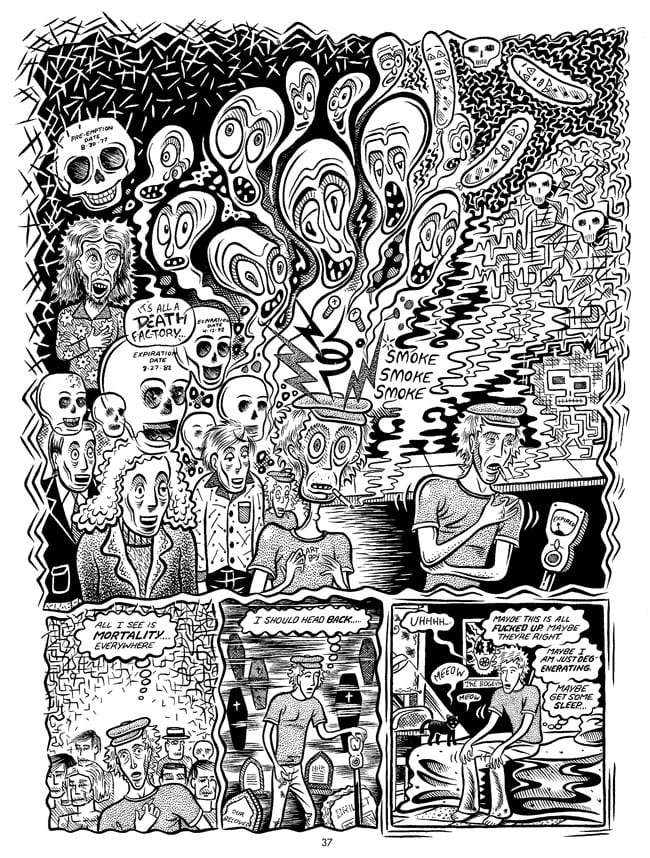

Head’s artwork throughout Chicago is outstanding. As Gloeckner points out in her introduction, his influences, ranging from S. Clay Wilson to Kim Deitch to Rory Hayes, are evident, but Head’s vibrant lines, richly detailed, panoramic splash pages, and deep, painterly blacks are in a class unto themselves, with certain sequences practically popping off the page. He has a special talent for limning wild, trippy, hallucinatory scenes in particular:

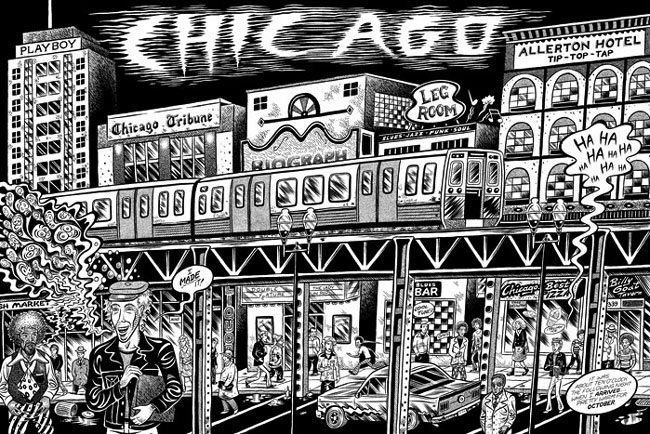

Then there’s this spectacular two-page splash heralding Glen’s gleeful arrival in the Windy City (unfortunately reduced in size here):

With its right-to-left rather than left-to-right reading order, Head’s re-sequencing of space and time here adds to the scene’s sense of heady disorientation. I found myself coming back to this drawing over and over again, examining and admiring all the little details.

In producing his first long-form work rather late into his career, Head has made the most of the opportunity. Chicago is a well crafted, impeccably rendered, and mature book, an amalgamation of different underground and alt-comics traditions blended into something fresh, gripping, and elusive. It does require more from readers than many other works of its nature, but give it some time after finishing, let it sink in a bit. The rewards are there.